:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/JPJHXR5CGSNR4LKQF5ZKLCCVYQ.png)

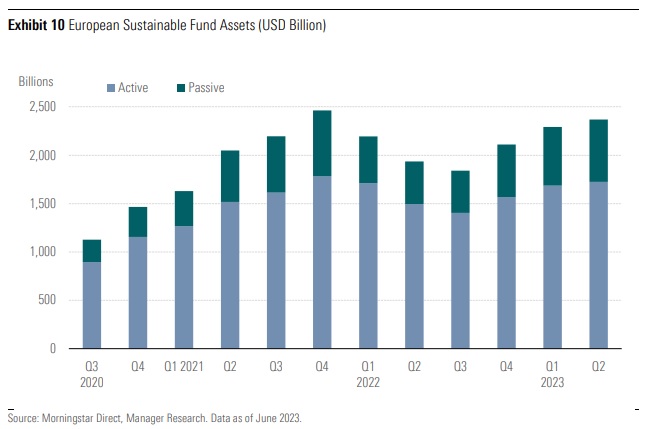

Passive management is gaining ground within the sustainable investment universe. In Europe, the amount of money flowing into sustainable index funds has almost tripled in the past three years.

According to Morningstar, about 28% of all sustainable assets invested in Europe – which account for 80% of global assets – are passively managed. Meanwhile in the US, a much smaller market when it comes to ESG, passive strategies are close to accounting for 40% of total assets.

But while these funds are becoming more mainstream, a lot of investors are unaware of just how diverse these strategies can be.

In order to create a passive fund, one needs a benchmark, and if it’s to be a sustainable fund, it would need an index constructed according to ESG (environmental, social, governance) criteria. In most cases, the starting point is a traditional index, to which filters are applied. These can be negative and/or positive, in order to eliminate issuers that do not meet the right criteria, and the reduction of the starting universe will depend on how strict the filters are.

Indeed, sustainable benchmarks are refining their methodologies, not least because of an increasingly important database of available data, both quantitatively and qualitatively. But let’s take a step back to understand how far these indices have come.

Where did Sustainable Index Funds Start?

A pioneer in the field of international ethical indices was the Domini Social Index 400, launched in 1990 by the US sustainability research and analysis company KLD. KLD was later acquired by Risk Metrics Group, which, in turn, was acquired by MSCI. The index is now called MSCI KLD 400 Social Index. An important milestone in the development of ethical indices was marked in 1999, when Dow Jones introduced the ethical Dow Jones Sustainability Index (DJSI) in collaboration with Swiss Sustainable Asset Management. Today, the DJSI is actually a family of ethical indices; the most important is the DJSI World, which includes about 10% of the world's largest 2,500 listed companies with the best ESG performance.

In 2001, the London Stock Exchange adopted an index inspired by the principles of social responsibility. With the advice of the British research institute EIRIS, the FTSE4Good basket was thus launched. In Italy, the first ethical indices were presented by Borsa Italiana in 2010.

“In the early 2000s, the market for sustainable benchmarks underwent a fundamental shift,” says Thomas Kuh, head of ESG strategy at Morningstar Indexes, “with the move away from strictly ethical principles and towards more structured methodologies that were also suitable for institutional investors. One of the important changes was to use mean-variance optimization in benchmark construction to manage risk while maximising exposure to companies with high ESG scores.”

More Complex, More Transparent, More Useful

If the first sustainable indices were essentially based on a mere logic of exclusion, we can say that the expansion of research and the use of increasingly precise and in-depth data have allowed 'sustainability' to permeate substantially all asset classes and to rely on increasingly refined construction methodologies tailored to investors' needs.

“ESG indexes, like any others, are designed to represent a market or a specific strategy,” Kuh continues. “They must be able to be taken as a reference by active managers and be able to be replicated in order to offer a transparent, efficient and low-cost passive product in line with investors' objectives.”

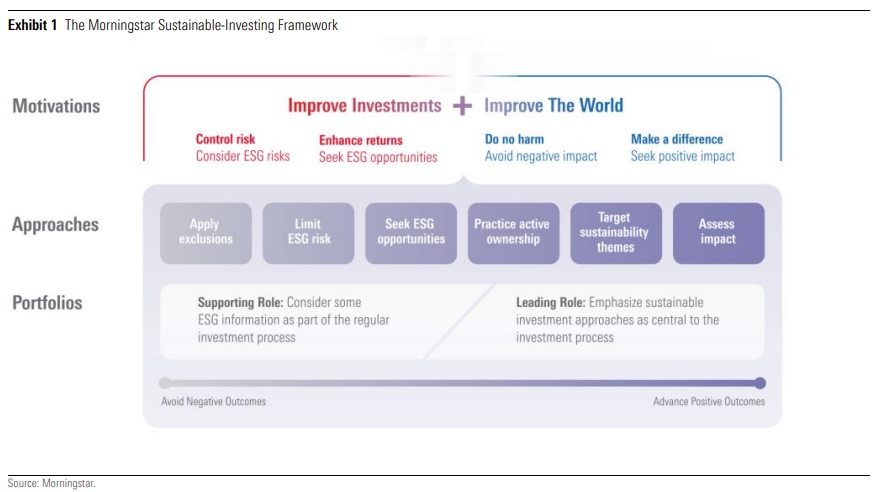

But sustainable investing is not monolithic. Approaches vary in terms of motivation, implementation and enforcement. The Morningstar Sustainable-Investing Framework illustrated below, for example, shows a broad spectrum of approaches with different objectives and profiles. It should be emphasised that approaches are not mutually exclusive. Many sustainable investments incorporate more than one approach, such as applying exclusions and limiting ESG risk.

Kuh predicts that ESG benchmarks and passive management in the field of sustainable investing will become more and more central.

“It will be similar to what happened with passive factor investing, only that in this case – unlike factor strategies – institutional investors will be able to allocate a large part or even the entire portfolio to ESG approaches. The potential is therefore much bigger and more important in terms of total assets.”

He adds: “The activity of engagement will become more and more present, as it makes sense to combine passive ESG management and engagement activities because they are long-term buy-and-hold strategies.”

Climate is King

If there is one field in which sustainable indices are particularly advanced, it is the environmental field – and the Paris conference in 2015 was a definitive turning point.

Kuh explains: “There were already climate-related benchmarks in existence, but since 2019 we have seen a strong uptake of Paris-aligned portfolios (PABs: those benchmarks whose level of total emissions is in line with what was agreed at COP21 in Paris, Ed). And today, net-zero is unquestionably at the centre of the agenda.”

Morningstar, for example, launched its range of Sustainable Environment indices in 2018 and two climate indices to help investors meet the European Union’s Climate Transition Benchmark (CTB) and Paris Aligned Benchmark (PAB) requirements in 2021.

But even here, approaches may be varied: some investors prioritise decarbonisation of the portfolio, while others may focus on green technologies. The integration of impact objectives could be another point of divergence.

Each approach has their own risk/return characteristics, and investors aiming to invest in solutions to combat climate change might be surprised by the carbon intensity of some companies involved in renewable energy, transition technologies, and climate action, Dan Lefkowitz, strategist at Morningstar Indexes, says.

“What accounts for their carbon intensity? First, many companies are involved in both fossil fuels and renewables – for example, utilities transitioning from coal to energy sources like wind and solar. Second, a company can be focused on products and services that are climate-friendly – electric vehicles, wind turbines, solar panels, or the basic materials that power green technologies – but have carbon intensive operations. This can even be true of semiconductor manufacturers whose chips enable energy efficiency,” Lefkowitz explains.

In short, the construction of climate indices is more complex than one might think, especially in the case of strategies such as those aligned with the Paris Agreement, which in 2022 suffered from the rally of the traditional energy sector.

It’s a Long-Term Proposition

For climate investors, and sustainable investors more broadly, it's important not to make too much of short-term performance fluctuations. Investment returns must always be analysed in the context of the approach and the biases inherent to the strategy. In the case of climate investments, low carbon, fossil fuel-free, and low-ESG-risk approaches can hew closely to the market. They tend to exhibit a growth bias with higher tech exposure.

By contrast, renewables, green technologies, and impact-oriented investments tend to be far more focused and narrow. They deviate further from the market and are generally more volatile. Heavier exposure to old economy sectors cannot only result in higher current emissions and ESG risk, but also act as a drag when tech-oriented stocks lead the market. On the plus side, they are more impact-aligned and hold up better during tech crashes.

Just as sustainability goals must be understood and balanced, climate investors need to set realistic expectations for risk and return.

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6BCTH5O2DVGYHBA4UDPCFNXA7M.png)