In 2015, every allocator wanted to talk about the holy grail of global absolute return funds. These macro investment products promised the trifecta of high returns, low risk, and low correlation to stocks and bonds – all packaged in daily liquid, low-cost UCITS funds.

Standard Life was the standard bearer. Its two flagship Global Absolute Return Strategy (GARS) UCITS funds commanded, at their peak, a staggering £40 billion pounds-plus in assets.

Other prominent asset managers smelled money and flogged similar products. A stampede of wealth managers and institutions threw, by some estimates, hundreds of billions of dollars at the space. Then the bubble deflated.

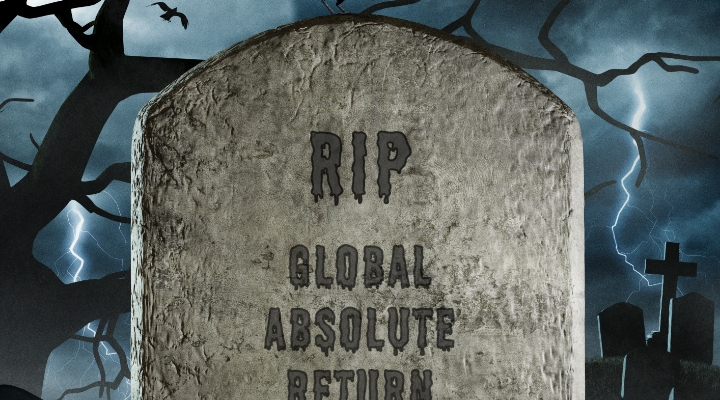

While equities have doubled since 2015, those two GARS funds have managed to lose money (and are having a miserable 2023). Not a mesmerising train wreck, perhaps, like we see in a hedge fund land blow-up; rather, just dead money.

Disillusioned investors steadily threw in the towel, and the GARS funds have shrunk by 97%. Peers have suffered, too, if not quite as Icarus-like. Today, many allocators cynically refer to them as "absolutely no return" products or, if they caught the fever 10 years ago, avoid talking about it. Yesterday’s favorite product has become today's Voldemort.

The question is, what the hell happened? And what can we learn from it?

Why Did GARS Die?

For background, I bumped into the space at peak frenzy in 2015, when a prominent US-based asset manager asked us to help them build a UCITS hedge fund product.

One target criteria "cash plus 5% with low risk" – piqued our interest. Equities can deliver "cash plus 5%" but brace yourself for gruelling bear markets. Bonds are steadier but don't give you much more than cash over time. Higher returns and higher risk go hand in hand.

To hit that bogey, you need an awful lot of alpha. Alpha is devilishly elusive. When big investors find someone who has cracked the code – a hedge fund like Millennium or Citadel – they'll gladly tie up money for years and pay eye-watering fees. It's just not something you often find in "everyman" products.

Curious, we started to dig around. A friend pointed to Standard Life. With little more research, we understood why. Over the preceding eight years, GARS has trounced equities and bonds. Alpha was over 5% a year. These guys were running circles around 90% of hedge funds and looked like magicians.

It looked too good to be true and it was. Yet smart allocators across the UK and Europe were jumping in with both feet. The answer why is fascinating and, lies, in part, in the nature of the asset management business. It's built to sell "hot dots" funds with great, but unrealistic and unsustainable performance.

Inside The Game

Here is how it works.

Big firms launch dozens of funds and build big distribution teams. Salespeople, motivated by up front commissions, mobilise to sell the winners. Marketing dollars fuel the narrative.

Skill, not luck, drove outperformance, they say. Back in the 1990s, one prominent US firm was believed to have launched a dozen funds in January, shot nine by Christmas, and taken-out full-page ads on the winners at year-end.

Competitors smell money and jump in with copycat products. Without track records, they sell the space and why their bells and whistles will work better. Sceptics, of course, are run over. Plant a flag too early, and you look like a fool when the streak continues.

And early adopters don't help. A platform or allocator who caught the wave early looks like a genius and makes sure everyone knows about it. Their peers bristle with envy and race to catch up. As the bubble grows, it feeds on itself: more players, more funds, more dollars, and more resources.

How Can Allocators Protect Themselves?

Most importantly, recognise the game.

The job of asset managers is to sell you something, and your job is to question. Ask them hard questions to level the playing field: list all their funds in the space, dig up the dead bodies, find out what funds they sold three years ago and how those fared, who gets paid what. Then look farther afield – study what didn't work, like here. Talk to people with no skin in the game.

There's no perfect answer. Fund selection is a very, very difficult game. Job one is to avoid stepping on landmines. And there are plenty out there. Caveat emptor applies.

Andrew Beer is founder and managing member at Dynamic Beta Investments