There are times when hedging an equity portfolio is greatly rewarded. The two obvious cases were during the great depression, when government bonds profited as equities plummeted, and in the 1970s, when stocks lost ground to inflation while commodity prices soared.

However, those examples also illustrate the drawbacks of hedging. First, they rarely occur. Under all but highly unusual conditions, risk-tolerant investors who have moderately long horizons can earn their way out of trouble. Stocks take a beating here and there, but within a few years, they recover their losses. Safeguards prove unnecessary.

Second, there is no single winning hedge. Treasuries saved the great depression’s investors, but one generation later, long bonds fared even worse than equities.

The opposite held for commodities, which had been no help at all during the 1930s. During the shorter bear markets of more recent years, a similar pattern has held. Long, high-quality bonds were terrific in 2008 and 2020 but abysmal in 2022. Meanwhile, commodities flubbed two of their three opportunities.

Liquid Alternatives

Today’s article addresses a newer form of hedge: liquid alternatives.

Consisting of strategies that short securities as well as hold long positions, liquid alternatives are the mutual fund/exchange-traded fund version of "hedge funds", which invest similarly, but through private funds sold exclusively to accredited investors. (The irony quotes signify that hedge funds do not always hedge, although liquid alternatives – which do not have the word "hedge" in their names – reliably do. I trust you are now suitably confused.)

Most liquid alternatives funds invest in a single strategy, but some, which Morningstar calls "multistrategy," combine several alternatives into a single fund. Because multistrategy funds accurately represent the overall group, I use their returns for the computations that follow.

A Promising Start

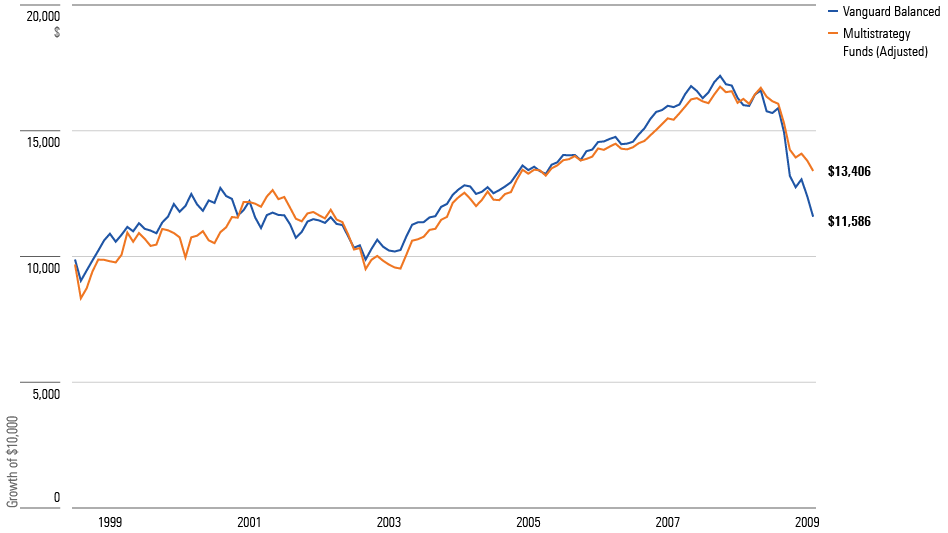

Let’s begin our inquiry 25 years ago, in July 1998, when multistrategy funds were first appearing. Their initial performance was encouraging. Over the next 11.5 years, the investments made by multistrategy funds outgained those of Vanguard Balanced Index VBINX.

In Theory...

(Growth of $10,000, July 1998-February 2009, with Expense-Ratio Adjustment)

Regrettably, that presentation cooks the books – twice. For one, it ignores cost disparities. The above calculation equalised the competitors by assuming multistrategy funds cost the same as Vanguard Balanced Index. That was a great exaggeration. Whereas the investor shares of Vanguard’s fund currently have a 0.18% expense ratio, multistrategy funds average a whopping 1.75%.

After accounting for that discrepancy, multistrategy funds forfeited their return advantage. The contest was tight: multistrategy funds converted an initial $10,000 investment into a closing $11,341, while Vanguard Balanced Index finished at $11,586. What’s more, the alternatives funds were less volatile. While one might regret their high costs, they had unquestionably answered the opening bell.

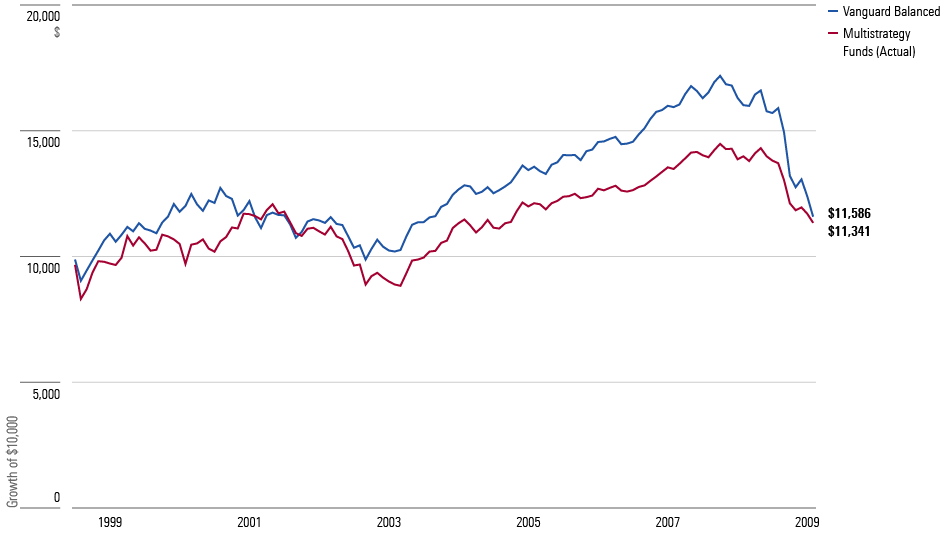

In Practice

(Growth of $10,000, July 1998-February 2009)

The Longer View

Then the other shoe dropped.

The initial market environment showcased alternative investing’s strengths, as it was a turbulent period bookended by the 2000-02 technology-stock crash and the 2008 global financial crisis. Given that climate, it was no surprise that multistrategy funds had fared relatively well. Worrisomely, they outgained Vanguard Balanced only after assuming away their extra expenses. That would not bode well for their bull-market competitiveness.

And indeed it didn’t.

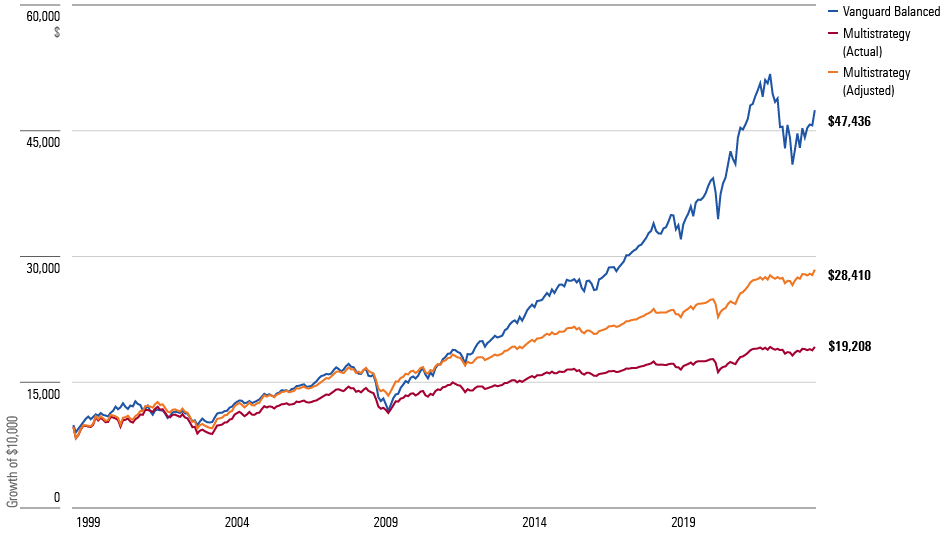

Since 2009, multistrategy funds have been left far, far behind. Today, even their cost-adjusted results trail those of Vanguard Balanced Index by almost $20,000. Their actual results, of course, have been worse yet. Barring a stock market catastrophe, multistrategy-fund investors will never catch Vanguard’s fund. The gap has become too large.

Left Far Behind

(Growth of $10,000, July 1998-June 2023)

As a Hedge

This discussion, I must confess, has not been entirely fair to liquid alternatives. By and large, they have been sold as a supplement to traditional securities, not a substitute. Multistrategy funds should therefore be evaluated in that role, rather than as a stand-alone investment.

That reply, however, is refuted by this column’s charts. Even a cursory glance reveals that when the blue lines representing Vanguard Balanced Index have headed south, so too have multistrategy funds. Had the lines significantly diverged, replacing a portion of Vanguard Balanced with alternative investments could have substantially improved a portfolio. Instead, though, multistrategy funds have behaved as muted versions of balanced funds.

That offers no real help.

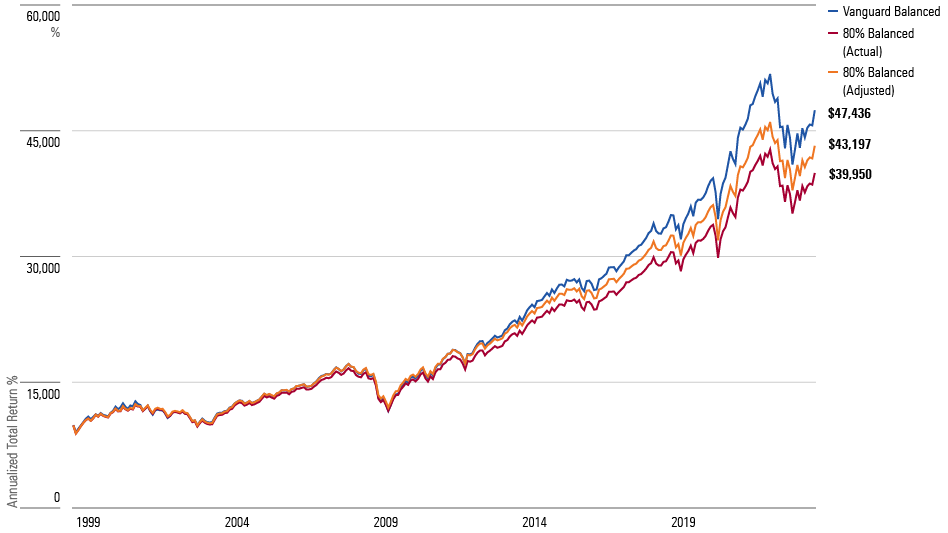

The outcomes support the assertion. The following chart once again depicts the 25-year performance of Vanguard Balanced Index, this time compared against 1) a portfolio consisting of 80% Vanguard Balanced Index and 20% multistrategy funds, cost-adjusting the latter; and 2) the same approach while using actual expense ratios.

The Hedged Approach

(Growth of $10,000, July 1998-June 2023)

Conclusion

Multistrategy funds have failed balanced-fund investors. In 2022 they were genuinely useful. That year, multistrategy funds almost broke even, while Vanguard Balanced Index, hurt by both its stock and bond positions, shed 17%. The hedged portfolio would have lost 14%. Otherwise, though, liquid alternatives had no material effect. In 2008, for example, the hedged portfolio declined by 21% as opposed to 22% for Vanguard’s fund. Whoop-de-do.

Perhaps a 20% position in liquid alternatives is insufficient. Truly protecting against balanced-fund losses may require additional medicine. Unfortunately, as this article has shown, adding enough liquid alternatives to make a significant bear market difference will likely torpedo the portfolio’s long-term returns.

To be sure, this is but one example – a single (albeit popular) flavour of hedge, applied to a single (if also popular) flavor of portfolio. Selecting different investments would change the numbers. But the principle remains: most hedges do not make enough money to justify their inclusion, especially after costs. The insurance is not worth the premium.