Inflation has eased substantially in the US without throwing the economy into a recession. As such, we are very confident that it is possible to achieve a soft landing – contingent on astute monetary policy.

We see about a 30%-40% probability of a formal recession being declared, but we think a recession will be short-lived if it does occur.

We also remain bullish on long-term gross domestic product growth. We project GDP growth to start bouncing back in the second half of 2024 as the US Federal Reserve pivots to easing monetary policy, showing up as robust growth in the 2025, 2026, and 2027 annual numbers.

These forecasts haven’t changed much since our last update, as data has largely flowed in as expected.

We have notched down 2024 growth slightly as we expect banking credit growth to contract with banks tightening lending standards. Still, this development won’t cripple the economy.

In terms of our longer-run growth outlook, we’ve dialled back our productivity assumptions likely on continued weak performance but raised our labour supply forecast as participation rates recover.

We Maintain That Inflation Should Fall in 2023

Our inflation forecast has ticked up slightly compared with a month ago but the story remains the same. We still expect an aggressive drop in inflation through the end of 2023, and in 2024 and following years, we expect the Federal Reserve to undershoot its 2% target. This is driven by the unwinding of price spikes caused by supply constraints along with a moderated pace of economic growth due to Fed tightening.

As shown below, we expect inflation to drop to 3.5% in 2023 and average just 1.8% over 2024-27.

These views diverge significantly from the consensus. While consensus has partially given up on the “transitory” story for inflation, we still think most of the sources of recent high inflation will unwind in impact over the next few years, providing prolonged deflationary pressure. This includes energy, autos, and other durables.

Should inflation prove stickier than expected, we still expect the Fed to get the job done, but that scenario would require a more severe (and thus deflationary) economic downturn than we’re anticipating.

We Expect Interest Rates Will Soon Be Headed Back Down

We think this falling inflation will pave the way for the Fed to pivot back to easing by the end of 2023.

The Fed will need to lower interest rates to avert a greater fall in housing activity and eventually generate a rebound. This should allow GDP growth to reaccelerate over 2024-26, as we expect.

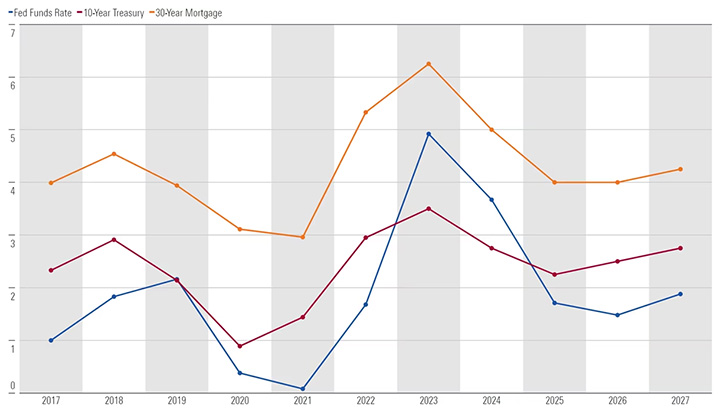

As shown below, by 2027, we expect monetary policy with a neutral stance, with the federal-funds rate and the 10-year Treasury yield in line with our assessment of their long-run natural levels.

As for the bond market, it has moved closer to our views recently, though there’s still a small gap. The five-year Treasury yield is 3.7% as of May, implying an average fed-funds rate of around 3%-3.5% over the next five years. By contrast, we expect an average effective fed-funds rate of about 2.5% over the next five years. Likewise, the 10-year Treasury yield is 3.7%, above our long-run projection of 2.75%.

GDP Rebounds Strongly in Third Quarter as Former Headwinds Reversed

We’re upbeat on US economic growth, as we expect a cumulative 4%-5% more real GDP growth through 2027 than consensus.

In the near term, the divergence is driven by our view that falling inflation will allow the Fed to cut rates and jump-start the economy. In the longer run, we’re more optimistic about supply-side expansion, both in terms of labour supply and productivity.

Our bullish view on GDP through 2027 compared with consensus is driven greatly by our expectations for labour supply. We expect labour force participation (adjusted for demographics) to recover ahead of pre-pandemic rates as widespread job availability pulls in formerly discouraged workers; while consensus expects labour force participation to struggle to reach pre-pandemic rates.

Despite Some Areas of Vulnerability, Commercial Real Estate Unlikely to See Violent Bust

Those fearing a broader bank crisis have often mentioned commercial real estate as an area of concern. One reason is that exposure is concentrated among smaller banks (those outside the top 25 in assets), which hold about 67% of all commercial real estate loans. But the underlying credit risk from commercial real estate looks very manageable. Total US investment in non-residential structures as a share of GDP was well within historical norms prior to the pandemic and has actually trended down slightly since then – so there’s not an overhang of excess non-residential structures in general. This is a stark contrast with the overbuilding of housing in the 2000s.

Within the realm of commercial real estate, office buildings have the most vulnerability, owing to the persistent adoption of remote work by white-collar workers. Still, even at pre-pandemic (2019) rates, office construction only accounted for 13% of non-residential investment, or just 0.4% of U.S. GDP.

A Crisis Isn’t Developing, but Banks Will Cut Back Lending

In accordance with our bank equity research team’s 2023 outlook, we don’t expect a broad crisis in the banking sector. The issues which brought down Silicon Valley Bank, Signature, and First Republic look mostly idiosyncratic in nature.

The ultimate cause of deposit outflows for the banking system is the yawning gulf between deposit rates paid by banks and rates paid by other short-term investments (namely money market funds), which track the fed-funds rate.

It shouldn’t be forgotten that the sluggish increase in deposit rates is helping banks march toward cyclical highs in net interest margin and overall profitability. As highlighted in our banking outlook, some mean reversion from peak profitability is hardly a reason for panic.

Admittedly, there’s some uncertainty about how much higher banks’ cost of funding could go. The response of ordinary bank depositors to attractive yield differentials is driven as much by psychological factors as rational calculation. Even with the Fed pausing on rate hikes, we do expect deposit rates to creep higher, but this late-cycle behaviour isn’t unusual. We also think that credit losses in commercial real estate and other areas should be manageable.