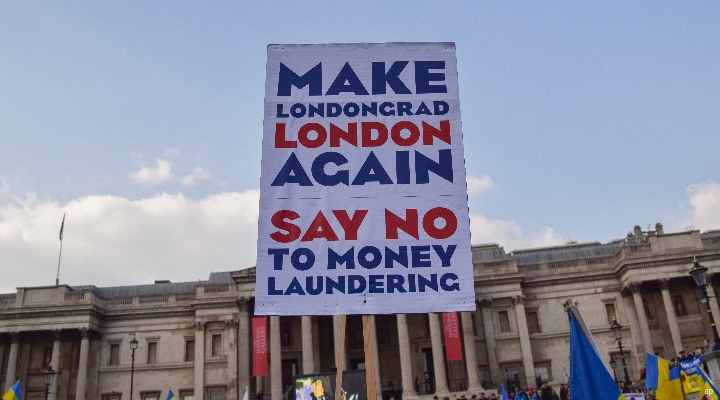

In what seems like an eternity ago, Russian influence in the British capital led to a nickname infamous enough to attract the attention of journalists, traders and criminals: Londongrad.

With money pouring in from the east for over two decades (some of it ill-gotten) London estate agents celebrated the influx of "cash buyers" who zoned in on the capital’s most desirable postcodes.

In parallel, the same type of people were floating companies and raising money in London (more on this in another article). Before the financial crisis, the general public didn’t really ask too many questions about how people made their money – as long as their own house was rising in value and the good times rolled.

As interest in Londongrad grew, politicians paid lipservice to cleaning up the capital’s "laundromat" reputation, but tycoons were also manoeuvring themselves into positions of power that made them harder to restrain – if not untouchable.

In recent years, however, the net has been tightening on dirty money. "Unexplained Wealth Orders" were brought in 2017 and have forced asset seizures and freezes across the capital.

Then came the invasion of Ukraine, and with it a resetting of London's moral compass.

This hard stop shone a harsh light on failures of government and regulators to tackle dirty money. Today, the London property market – which is much more lightly regulated than the City of London – has had to get full square behind the UK sanctions regime.

Step forward estate agents, who have become the unlikely front line against organised crime, money laundering and sanctions-busting.

No Cheeky Offers Please

What’s really happening on the ground? Are Russian buyers sorely missed in London – and has anyone replaced them? Have the oligarchs been turfed out of their mansions?

To answer these questions, I asked a property buying agent, Henry Pryor, who knows the high-end London property market inside out. Buyers haven’t just dried up, he says. They've vanished. He hasn’t seen any enquiries from Russian or central Asian buyers for a year.

Anyone hoping to make what’s known in the trade as a "cheeky offer" on a Kensington town house may have been disappointed. When the government sanctions people, their assets are frozen, which means they can’t be bought or sold. If they still live in the property they may have to sell eventually, whether through death or divorce, but in the meantime, the owner is in limbo because the state hasn’t worked out a way of claiming and selling the house, Pryor says. After all, the UK's property rights and contract law are what it make it attractive. The state can freeze your assets but it can't seize them, per se.

It's hard to quantify how much of the London property market relied on Russian buyers and sellers in previous years. But are they missed?

Not really, says Pryor. There are plenty of millionaires and billionaires from other countries. "The oligarch market is as strong as ever," he says.

Market research suggests that, despite a wider slowdown in UK housing, the niche market where houses worth £5 million and above are bought and sold had a great 2022. Ironically, this would be a good time to sell if you were able to. The number of billionaires globally increases every year, and London is one of those high-profile cities like New York that appeals to overseas investors.

Know Your Customer

What about estate agents? A new wave of risk aversion has taken over. Even Russian buyers that aren't on the UK sanctions list trigger suspicion. Buying and selling houses is time-consuming and tedious enough without every link in the chain raising red flags.

Like wealth managers and financial advisers, the principle of "know your customer" is well established; this means not just finding out what you do for a living, it involves probing where your money came from. The bigger the sums involved, the more serious the questions asked.

"Nobody’s got the patience to try to onboard you," Pryor says.

"Everbody involved is going to be suspicious [...] and that’s what’s going to bog you down," he adds. Money laundering regulations are onerous even at the best of times. Some of the biggest estate agents have had to walk away from deals – and the lucrative commission – because the hassle and time factor can be too daunting.

That said, an individual with a clean bill of financial health who is determined to press on with the transaction will still be able to, Pryor says. "If you’ve got enough patience and enough time you can push through the system," he adds.

But many potential buyers are hunkering down and waiting for better times, he argues. A similar approach can be seen in capital markets – if your assets and investments are frozen, there’s nothing you can realistically do unless the sanctions are lifted.

Criminal Cash

What about London’s tainted reputation as a conduit for criminal cash? Pryor is very clear that "the market should suffer from the exclusion of dirty money"; a healthy market should be able to function without it.

Is London now 100% clean? The Russia saga has "dented if not removed dodgy money", he says. Anti-money laundering rules have grown significantly in the last five years, he adds.

Having swung from permissive to hyper-vigilant, it’s possible that housing market regulation may find an equilibrium at some point in the future. There’s no room for complacency.

Despite the Register of Overseas Entities coming into effect in August 2022, it’s still hard to find out who really owns UK properties bought by foreign companies. A report by BBC News and Transparency International revealed nearly 50% of firms failed to declare who was the real owner. The financial world encounters this issue too, and it's on high alert for attempts at sanctions-dodging.

Ultimately, as long as there's a lack of transparency, property will always attract those with something to hide. As an asset class, it's proved itself as a store of value and income. But it's also a store of secrecy, and that hasn't changed.