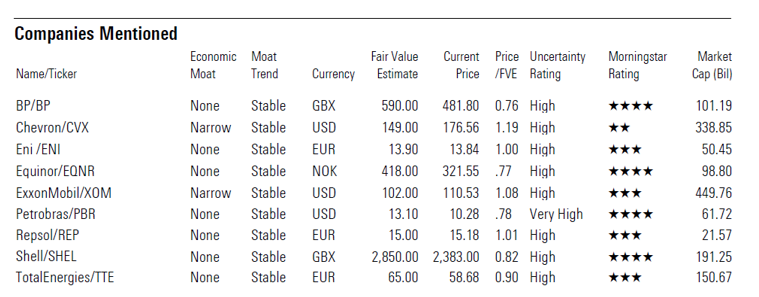

Morningstar has just published a report (Annual Check-Up: Integrated Greenhouse Gas Emissions) comparing some of the world's largest oil companies regarding their emissions.

The objective of the report is not to modify the fair value estimates or the moat ratings of these companies on emissions performance but to monitor their progress and the year-over-year change. However, it is the adoption, and ultimately the achievement, of long-term emissions-reduction targets, which is influencing today's capital allocation decisions, and those in turn affect valuations and moats.

European Oil is More Ambitious

European integrated oil emissions targets are more ambitious than the American ones. The reason is that all European integrated oil companies have signed up for Net-Zero Emissions 2050 that includes all emissions (including scope 3 emissions) while US firms, like Chevron and Exxon have also introduced Net-Zero Emissions 2050 targets, but only for operated emissions (scope 1 and 2) and, in Chevron's case, only for its upstream equity production.

Achieving net-zero targets that include scope 3 emissions can really only be achieved through a change in the type of energy supplied. That means that companies plan to do so largely with renewables such as wind and solar. European integrated oils' targets for renewable power generation capacity in 2025 and 2030 is a reflection of their capital plans. Exxon, Chevron, and Petrobras lack similar targets as they have no plans to enter the renewable energy business.

Equinor, The Best?

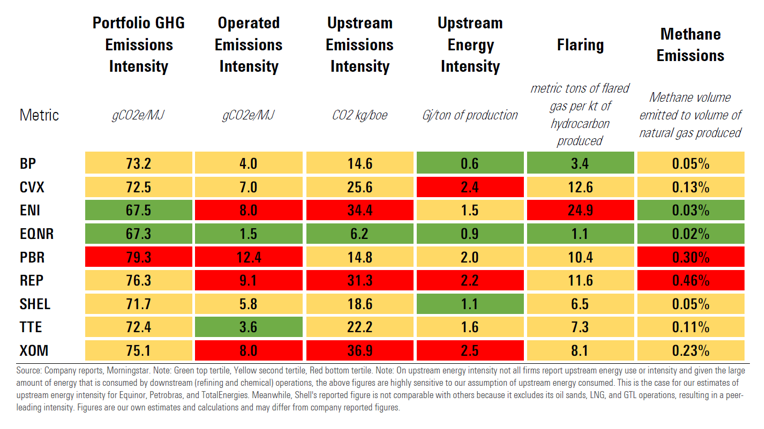

In general companies have demonstrated broad progress in 2021 compared with 2020. Measured across six standardized measures, Equinor continues to hold the lowest-emissions position, while Exxon, Repsol and Petrobras hold the highest-emissions position for many metrics, but there are reasons that have to do with the asset mix. As such, we do not see low or high emissions as a reason to invest in each company or not, but rather something to be aware of and monitor over time.

Greenhouse Gas Emissions Intensity

The greenhouse gas intensity metric is a measure used to compare the total emissions of a company's portfolio to others and to itself over time. The emissions intensity varies among companies due to their structure and composition. For example, Eni's emissions intensity is low because of its large natural gas distribution business. In contrast, Petrobras scores poorly because of its relatively low natural gas output and high operated emissions.

Improvement in emissions reduction has been slow and uneven, and will likely remain so, as companies have little control over scope 3 emissions. European firms have set a target of 20% reduction by 2030, but 90% of integrated oil emissions are scope 3, which occur during the combustion of oil and natural gas.

Operated Emissions Intensity

This metric only includes scope 1 and 2 emissions. However, it is also affected by differences in disclosures and can be influenced by differentiation among firms due to the structure of each company. Petrobras scores poorly because of the high emissions of its nonupstream segments, for example. By contrast, Equinor scores well because it's primarily focused on upstream and has low upstream emissions intensity.

Upstream Emissions Intensity

Upstream emissions intensity is largely a function of the type of oil produced. Exxon, Chevron, Repsol, and Eni perform poorly, while BP, TotalEnergies, Shell, and Petrobras are in line with industry averages. Only Equinor excels with below-average intensity.

Upstream Energy Intensity

Energy use is responsible for about 60% of upstream greenhouse gas emissions. Outside divesting heavy oil assets, firms can focus on efforts to electrify and incorporate renewable energy into production operations to reduce emissions.

Equinor stands out as a representative example given its push to electrify offshore platforms with low-emissions power. Divestment of energy-intensive heavy oil has also occurred. TotalEnergies is perhaps taking the most dramatic step by spinning off its oil sands operations into a new company in 2023.

Flaring Intensity

A key component to reducing emissions for integrated oils is the reduction of flaring, which is the controlled burning of gas for collection and use. It accounts for about a quarter of greenhouse gas industry emissions. Differences in flaring intensity are largely a function of geography of production. Historically, Eni and Chevron have stood out among peers due to their large African production base.

Methane Intensity

The importance of reducing methane emissions comes largely from its outsize effect on global warming. Although it only comprises about 5% of total scope 1 emissions on average, it holds greater warming intensity than carbon.

Each company mentioned in the report is a member of the Oil and Gas Climate Initiative and has signed on to target methane emissions intensity of well below 0.20% by 2025, with an ambition of nearly zero by 2030 from a baseline average of 0.30% in 2017.

Repsol stands out largely due to upstream assets it acquired in Malaysia in 2015, but it divested those in 2021, resulting in a decline, which should improve further in 2022.

Note: Scope 1 emissions come directly from company-owned or controlled sources; scope 2 emissions are indirect emissions from purchased energy; scope 3 emissions are all indirect emissions in a company's value chain, including upstream and downstream operations.