Investors can’t say goodbye to 2022 fast enough.

War. Severe supply shortages; inflation at the highest levels in 40 years; interest rates rising at a speed and by a size that was unprecedented; a bear market in stocks; an historic selloff in bonds; the tanking of Big Tech; the collapse of cryptocurrencies; the worst market for raising capital through initial public offerings in 30 years; a still lingering pandemic; the expression "cash is king" making a comeback; that was the year that was.

In hindsight, the risks were in plain view, if only anyone wanted to look.

Eventually, long-held market truisms, such as "buy the dip" in a market swoon and the sacrosanct nature of the "60/40" portfolio, in which bonds are balanced against stocks to shock proof portfolios, were sorely tested.

So what lessons can investors glean from 2022?

Valuations Matter

Graeme Forster, portfolio manager for international and global equity strategies at Orbis Investment Management, refers to the start of 2022 as the "everything bubble."

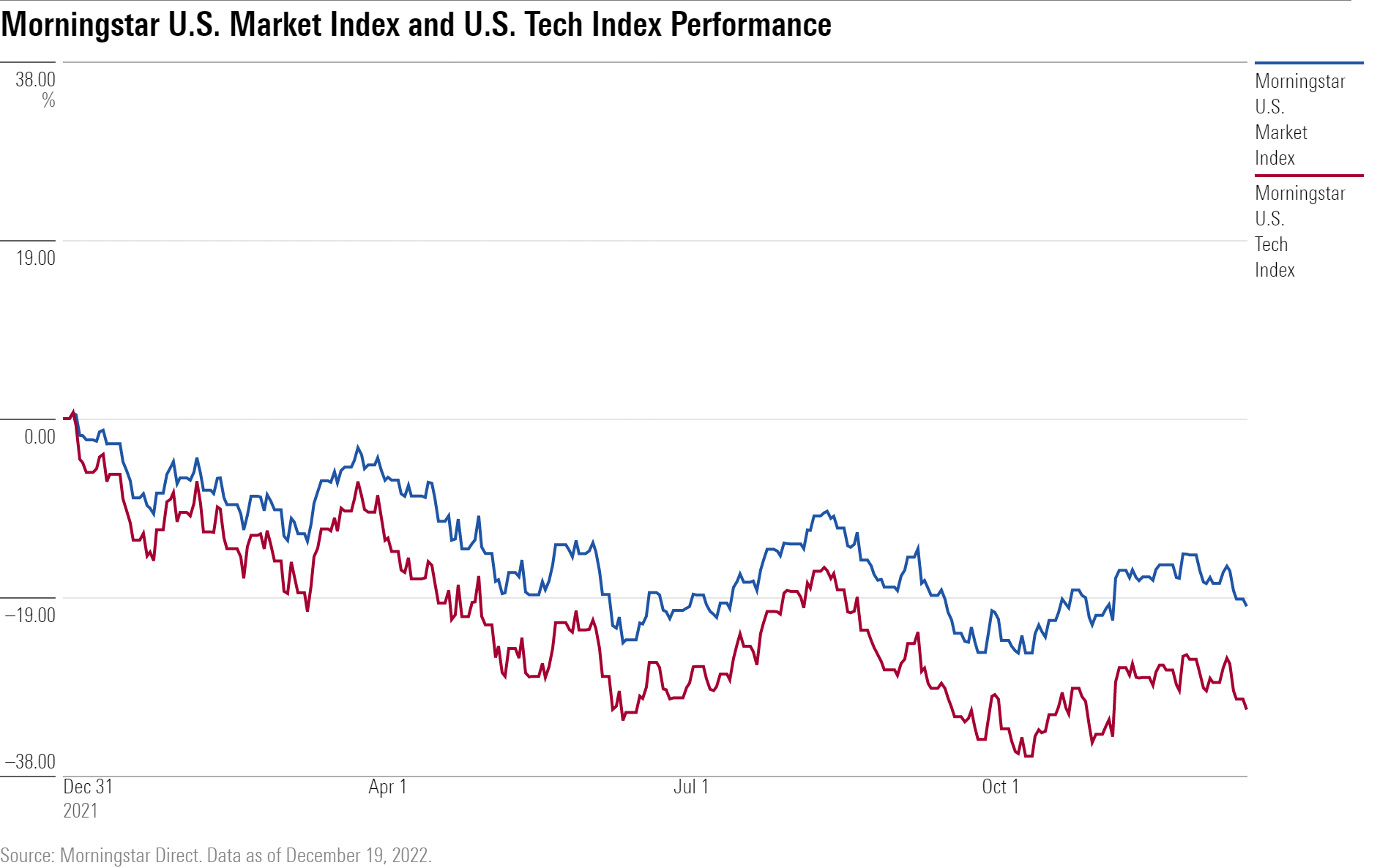

Stock market valuations hovered at all-time highs, particularly among the most dominant big technology stocks [think Meta Platforms (META), Alphabet (GOOGL), the parent company of Google, and Amazon.com (AMZN) to name a few] as "money flooded into new economy assets, including Tesla (TSLA) and NFTs (nonfungible tokens), and cryptocurrencies" a dynamic that resembled the "Nifty Fifty" era of the late 60s, the dot.com boom in the late 90s, and even Japan in the late 80s, he says.

"Any kind of growth stock traded at absurd levels," says Forster. "And absurdity rhymes every time," a play on Mark Twain’s observation that "history never repeats itself, but it often rhymes."

Some flagrant signs of the times as he sees it: a virtual yacht sold in the metaverse of an online game for more than $500,00, virtual real estate transactions in the metaverse totaled more than $500 million, and a digital Gucci handbag sold for $4,000, more than a real one, in the metaverse.

He compares the overinvestment in intangible assets to the underinvestment in real assets by old-economy companies, such as energy and commodity producers, which he sees as emboldening Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which resulted in supply shocks and an inflationary spiral.

Bonds, too, represented huge risks, with yields at historically low levels. Yet, investors behaved as if the long bull cycle in both stocks and bonds would go on forever, lulled by the events of the prior year in which the government turned on the fiscal spigots and loosened monetary policy to protect the economy during the pandemic. Easy money conditions inevitably lead to excess risk taking and the misallocation of capital, says Forster.

"Valuation was key this year," says David Sekera, chief US market strategist at Morningstar, who warned investors early on that the broad stock market was overvalued. "Investors need to know what they are paying for," he adds.

Indeed, value stocks – those whose prices typically don’t reflect their true worth based on their fundamentals and underlying assets – have delivered returns this year that have far outpaced their growth counterparts.

The Morningstar US Market Broad Value Extended Index is off nearly 8% this year compared with the Morningstar US Market Broad Growth Index, which has fallen more than 30%.

Interest Rates Matter

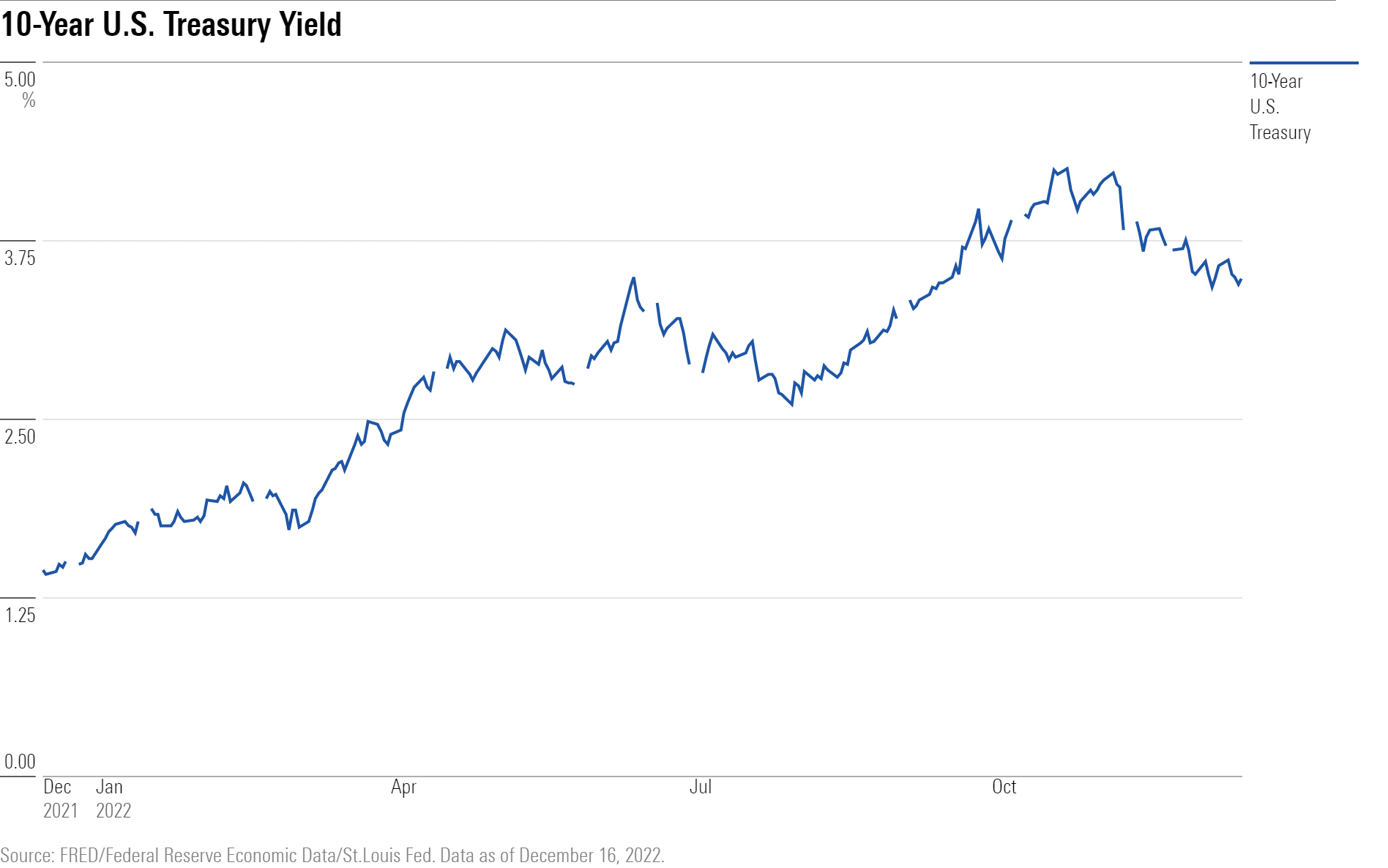

Never in our lifetimes has there been a collapse of bonds such as that witnessed this year. The yield on the 10-year Treasury, at a recent 3.59%, has more than doubled since the start of the year, clobbering prices. Prices move inversely to yields.

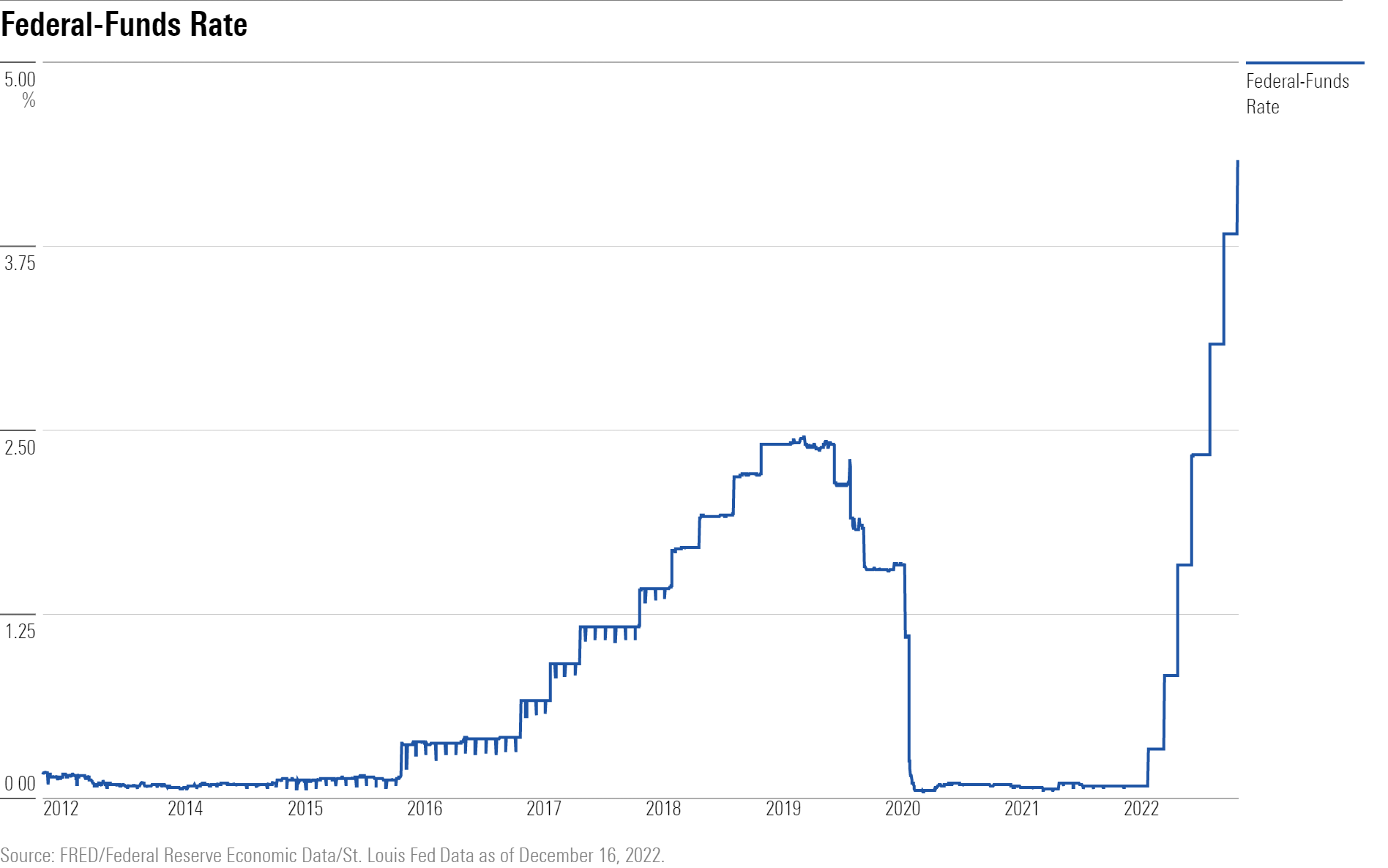

Blame the debacle on the swift and aggressive rate hikes by the Federal Reserve Board to tackle inflation after an extremely long stretch of ultralow interest rates. The federal-funds rate started the year near zero and is now at 4.25%-4.50%

Investors overlooked how risky the bond market had become and how even small interest rate hikes would amplify losses.

"The size of the move was huge and the speed has been unprecedented," says Eddy Vataru, lead portfolio manager for total return strategy at Osterweis Capital Management. "Usually, the Fed hikes slowly and cuts quickly."

"It was a trifecta: bonds produced no income, there were price risks, and a hyperactive Fed."

Long considered a source of safety and stability, providing ballast to volatile stocks, bonds' double-digit losses compounded investor woes in 2022. The Morningstar US Bond Index is down 11.19% this year while Morningstar's US Market Index is down more than 19%.

Deutsche Bank strategists, citing an index from Global Financial Data that uses proxies for long-term debt that go back centuries, have noted this year’s drop is the worst since a 25% drop in 1788, a year before the US Treasury was even established.

Even worse, investors also overlooked the relationship between stocks and interest rates and the "sensitivity of long-duration growth companies to interest rates," says James St. Aubin, chief investment officer at Sierra Investment Management, a Santa Monica-based investment management company. "It became clear how damaging interest-rate movements can be to technology companies."

As rates move higher, so do the costs of capital, and that erodes expected future cash flows and drives down valuations. High-growth companies, such as technology companies, are particularly susceptible because they tend to spend heavily to develop products at the expense of profits in their early stages as they aim to build market share.

During the TINA – "There is No Alternative" – years following the pandemic lockdowns, when interest rates were low and liquidity ample, technology stocks appreciated dramatically.

Higher interest rates have since spelled the end of TINA and "the money came out as fast as it went in," says Aubin.

Mortgage rates responded immediately to the Fed’s moves and have more than doubled in the past year, sending the housing market into a major tailspin as mortgage applications and refinancings declined, new and existing house sales spiraled lower, and new housing starts dropped to their lowest levels since May 2020. Housing prices remained high, nonetheless, because supply still doesn’t meet demand.

Inflation Matters

There would be no interest rate increases if inflation weren’t a problem.

The government stimulus programs that injected cash into the economy to help keep businesses and households afloat during the early stages of the pandemic and beyond played a big part in driving inflation higher, and helped set the stage for the seven Fed rate hikes we’ve seen in 2022. In the UK, the Bank of England is on its ninth hike in 12 months.

"The overriding lesson in 2022 is that fiscal policy deserves an equal amount of blame for creating the surge in inflation," says Phil Orlando, chief equity market strategist for Federated Hermes.

Other contributors include supply chain disruptions stemming from factory shutdowns and worker shortages due to Covid-19. Geopolitics played a role, too, as Russia’s war against Ukraine highlighted Europe’s energy and food vulnerabilities and drove up the cost of those commodities.

"If we had to characterize 2022 by one thing it would have to be the 'year of the existential crisis in natural gas in Europe'", says Olga Bitel, global strategist at William Blair & Co., a boutique investment management firm.

"Rapidly rising inflation on the back of constrained supply chains was abating heading into 2022, explaining why the Fed was sanguine. Then Russia invaded Ukraine and it was questionable whether there would be enough energy in Europe."

That led to price spikes in oil, natural gas, and food, and spurred the Fed to fight inflation in earnest.

Passive vs. Active Strategies Matter

And not the way you might think.

For some, 2022 revealed a problem in passive investing strategies, which track broad stock market indices and are typically more tax-efficient and cheaper than active strategies.

Buying an index fund or exchange-traded fund tied to a major benchmark such as the S&P 500 in early 2022 gave investors much more exposure than they likely knew of to a group of technology stocks that dominated the index, accounting for about one-third of the overall market cap of the index. That represents huge concentration risk. With index funds, there’s also no way to know whether you are overpaying or underpaying for the underlying stocks.

This wasn’t a concern between 2009-2018, when stocks rose by nearly 15% a year on average, and even less of a concern from 2019-2021 when they rose by 20% as low interest rates fueled demand for stocks.

Now, amid increasing volatility and rising interest rates, investors might be more discerning.

Actively-managed funds depend on stock-picking prowess aimed at delivering returns that outperform the benchmark indexes.

While many actively managed funds are often found to be "closet indexers," mirroring closely the very strategy they are trying to beat, they are often free to make moves to protect their portfolios, such as raising cash as many did this year.

"Maybe investors will become more conscious of what they own," says Forster of Orbis.

"Investing is about being sceptical against strong prevailing narratives. Crowds are often wrong and yet they will dictate the price of investments."