With a winter World Cup in full swing, football is very much centre stage at year close. Expensive stars like Lionel Messi, Kylian Mbappé, and Neymar de Silva Santos are living up to their hype and price tags, much to the pleasure of Paris Saint-Germain (PSG).

One of these players could conceivably be lifting the World Cup in a week or so, which will no doubt unleash a whole chain of new sponsorship, branding and merchandise opportunities for the individuals – and raise the value of PSG, which is run by Qatari businessman Nasser Al-Khelaifi. Teams are more than the sum of their parts, of course, with fans, form and football all in the mix – but having a team of superstars helps enormously in this era of sporting M&A.

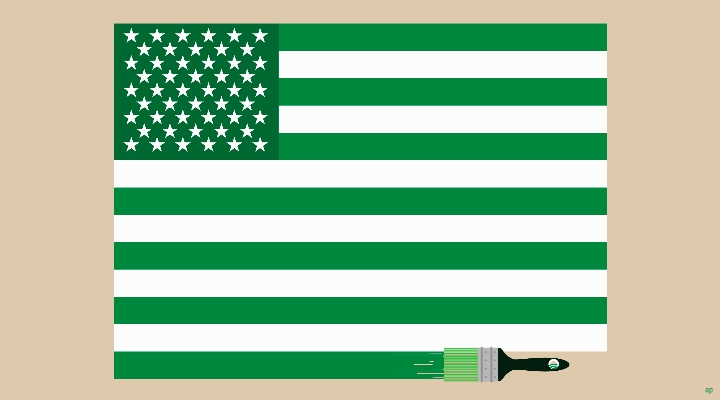

The USA's Big Say

Football’s commercial juggernaut rarely loses momentum, as I’ve written before, especially in a World Cup year. So this appears to be a logically sensible time for domestic "franchise" owners to put their clubs up for sale. It’s been a busy year already for football club sales, with Chelsea FC and AC Milan off the blocks already – and For Sale signs going up at Liverpool. There's even a tentative one for Manchester United, which is listed in New York.

Buying a football club used to be an expensive vanity project for bored billionaires, and a way of buying influence and even legitimacy. So sang David Gilmour in the Pink Floyd classic "Money", released way back in 1973: "new car, caviar, four star daydream // Think I'll buy me a football team".

Rich men’s money is still involved, but professional consortia are now the bidders, with private equity money mixed in. Why are clubs going for such high sums? A disappointing year for conventional and crypto assets may be a factor.

IPOs have been scarce, Bitcoin has plunged, and that may have tempted the serious money to look at alternative or "real" assets: while clubs pay out a lot in wages, they also bring in a lot of cash in gate receipts (pandemic aside), and the brand/marketing/sponsorship opportunities are lucrative.

No investments are strictly inflation- or recession-proof, but sports fans pay up during thick and thin. The price of a Premier League season ticket over the last 20 years has shown price inelasticity at work (the average is around £1,000 a year for the current season). Over time these investments have proved serious compounders, despite the heavy outlay needed at the beginning.

There’s also been a global shift in power away from Chinese/Russian investors to those from North America and the Middle East, the latter region boosted by oil price gains.

North America is hosting the next World Cup, and the region’s tycoons are deeply involved in European football: Liverpool is owned by John W. Henry via Fenway Sports Group, billionaire Todd Boehly was part of the winning consortium that bought Chelsea FC. Both Henry and Boehly have experience of owning successful US sporting franchises such as the Boston Red Sox and LA Dodgers baseball teams.

US private equity firms are also front and centre in providing the funding: Californian firm Clearlake won the bidding for Chelsea FC, and New York-headquartered RedBird Capital bought into Italy’s AC Milan this year.

Why Football And Why Now?

There are a number of reasons, argues Luis García Álvarez, portfolio manager of the MAPFRE AM Behavioral Fund and co-director of the Executive Program on Investment in Value and Behavioral Finance organized by ICADE Business School.

(Some) clubs are better run financially than in the past, and management teams (at board and pitch level) are increasingly professional and well-prepared. Scarcity is a factor too.

"This mass arrival of new investors into a market where supply is almost completely inelastic (meaning it’s virtually impossible to create new football clubs from scratch), is causing prices for these assets to rise sharply, and this trend is likely to continue. In our opinion, this influx of new money should result in attractive returns for those who are able to look ahead and select the right assets."

Thinking of stadia as real infrastructure assets helps too, Luis Garcia says.

"If they include spaces suitable for hosting corporate events, conferences, concerts, or other sporting events, why should the clubs that own stadiums limit their commercial activities to hosting a match once every two weeks?"

Media hype can be a double-edged sword, however. It brings intense attention at events like the World Cup and Euros (every four years) but could lead investors to overpay, because they get seduced by star quality, brand power and fan loyalty.

Now that the tech bubble has burst and the era of cheap debt financing draws to a close, could football franchises follow suit at some point? Having fans and brands may be powerful, but trophies are the only key metric in the footballing world: storied clubs like Manchester United and AC Milan have not won the Champions League since 2007-2008, while Manchester City (not for sale) appear to have a stranglehold on the Premier League, which it's won five times in the last decade.

And Paris Saint Germain? It may have the players and the money, but its Champions League wins total zero. Football is a star-studded affair, but you don't win on a wing and a prayer alone. No team wants to be all fur coat and no kickers.

James Gard is senior editor at Morningstar