Confession time: I was a chronic overspender.

I can trace the habit back to early childhood. It was the feeling of envy of people who ate branded cereal and had refrigerators with ice dispensers in the door. My parents were both hard workers, but they were just making ends meet trying to feed, house, and clothe four kids by working jobs that were just jobs, not careers.

For some, money represents freedom, opportunity, security, or peace of mind. For me, money was a barrier to my goals and dreams. It was the reason I couldn’t do or have the things I wanted in life.

Different people have different responses to growing up in an environment where money is scarce. Some become diligent savers and long-term planners, so they can avoid such a fate in adulthood. Some learn to be content with what they have. I became materialistic and eager to prove that I was “worth” as much as other people who had expensive homes, clothes, cars, and such. I’m not proud of it, but that’s how it was. I know I’m not the only one.

Through time, study, self-awareness, and experimentation, I’ve replaced financial self-sabotage with habits of mind and behaviour that make me both financially and psychologically better off. If you struggle with overspending, whether habitually or on occasion, I hope the process outlined here can help you make stronger choices that satisfy your desires without sabotaging your financial security.

Four Steps to Combat Overspending

Step 1: Admit Overspending Is a Problem

Stop rationalizing and start recognizing your weak points. Are there certain areas of spending where you tend to go overboard?

Maybe you get carried away buying gifts at the holidays. Maybe it’s an extra glass of wine when dining out. You might have all sorts of justifications for spending. Perhaps it’s “I deserve it!” Friends may urge you to “treat yo-self!” Whatever the trigger, you can’t make changes until you know where to put your focus.

Here are some prompts to get you started:

- Think of a time when you kicked yourself for spending or overspending;

- What did you buy or do?

- What were the emotions you remember feeling leading up to and just afterward?

This can be the hardest step because it requires honest self-reflection. The more honest you are with yourself, the more you can hone in on your true motivations, making lasting behaviour change more attainable.

I feel the urge to splurge when I feel bored, depressed, or insecure. If I’m not feeling like a particularly shiny version of myself, I’m tempted to upgrade my wardrobe or my home.

Initially, it feels good, but that quickly turns to anxiety and regret. In the long run, overspending costs me more than it’s worth in terms of peace of mind and self-respect.

Problem: identified. Emotions: named. That’s step one.

Step 2: Identify Your Need(s)

Learn the language of needs and strategies in money management. I’ve written extensively about this topic because it’s fundamental to making changes that are deeply satisfying.

In short, everything you do with your money is a strategy for meeting a fundamental human need. Needs are universal and relevant to all people everywhere. They fall into the following basic categories:

- Survival;

- Security;

- Love and belonging;

- Esteem;

- Meaning.

Some strategies for meeting our needs are effective, and some are not. Some are affordable, and some are not. The trick is to find a strategy that is both affordable and fulfilling for you.

When you adopt a needs-versus-strategies perspective, you get to the deeper motivation behind the spending, opening up new possibilities to meet your needs without spending more than you can afford. Use the clues you uncovered in Step 1 to pinpoint the need(s) that spending meets for you. Then think about the needs that overspending threatens.

When we learn to think this way, “I need a new outfit,” becomes, “I need to feel confident.” There are many ways to accomplish that goal that don’t involve going over budget. In fact, irresponsible spending will likely erode your self-esteem in the long run.

Step 3: Brainstorm New Strategies

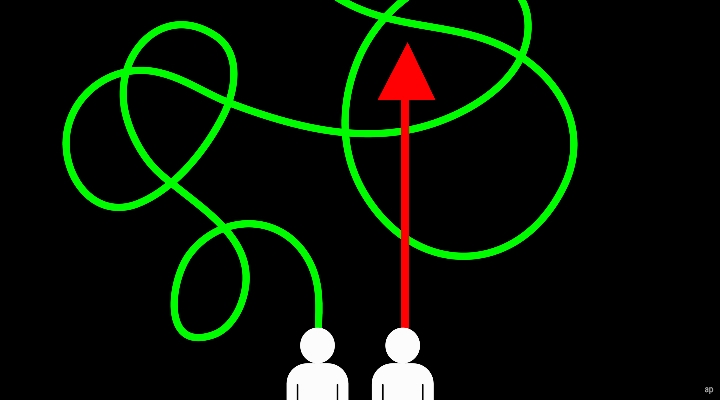

When we are focused on a specific strategy, we can become myopic, seeing only that or similar options. When we shift our attention to the need that is motivating the strategy, a whole host of new possibilities opens before us.

In keeping with the clothes example, once confidence and self-expression are identified as the motivation, then a strategy for meeting those needs may be found that reduces, or even eliminates, spending.

I remember the first time I walked away from a full shopping cart. I looked at the cart, realised I was motivated by negative emotions, and decided to skip the self-sabotage and walk away. I didn’t put things back. I didn’t whittle them down to budget. I left the cart and my habit right where they were and left. It was liberating and empowering, and more effective at boosting my mood than any purchase. I have learned that when the urge to splurge is rooted in insecurity, I can often meet the real need more effectively with sleep, reflection, time with friends, or a good sweat. None of these costs a dime.

When eliminating spending altogether is unrealistic, harm reduction can be useful. Spending less is better than doing nothing about the problem.

Here are some examples of harm-reduction strategies that might help you rein in your spending:

- Buying a new outfit from a clearance rack can be as fabulous as any other;

- Making cost-efficient gifts with love is often treasured longer than expensive gadgets;

- Resisting peer pressure may earn you more social capital than acquiescence;

- The least expensive drink on the menu still buys you time out with your friends.

I recommend having one or two alternatives thought through before you enter an environment where you will be tempted. The heat of the moment is a terrible time to problem-solve.

If it helps, write down your alternate strategies on a note card and carry it in your wallet. The next time you get the urge to splurge, it will be easier to think of alternatives because you will have already thought this through.

Step 4: Try, Try Again

Overspending isn’t something many people talk openly about, so it’s unlikely you will have a crowd of people to cheer you on as you navigate your temptations. You will probably need to be your own cheerleader. That can be tough, but be assured you are not alone. Millions of people struggle with overspending. Deciding to make a change is something to be proud of.

Some days will be easier than others. If the idea of never splurging again fills you with despair instead of pride, then take a page out of the addiction recovery playbook and focus on today. Can you find alternatives to spending just for today? If so, then go for it! Tomorrow, you can decide if you want to do it again.

Habit change takes time and repetition. One way to help solidify a new habit is to reward yourself immediately when you do the new thing instead of the old. The reward doesn’t need to be large.

Put a gold star on your calendar or in your journal for the day, and write down what you did and why you’re proud of it. Something as simple as a mental, “heck, yeah!” as you walk away might do the trick. However, you choose to do it, make sure you find a way to bask in the feeling of accomplishment and self-respect for at least a moment whenever you successfully resist temptation. This will help mentally reinforce the new pattern of behaviour.

You will probably slip. That’s ok. Overcoming overspending isn’t easy. You will have victories and slumps, but progress will happen over time if you persevere.

If I can do it, so can you! And, even though you can’t hear me, I’m cheering you on!

Sarah Newcomb is director of financial psychology at Morningstar