China’s stock market has extended already steep declines, battering widely followed emerging markets indexes and funds with heavy weightings in the country.

Last week, the Morningstar China Index fell 8.6%—its worst weekly drop since February 2021—following the close of the latest government’s ruling party congress. On October 24, the index lost 7.5% for its second-largest drop in 14 years.

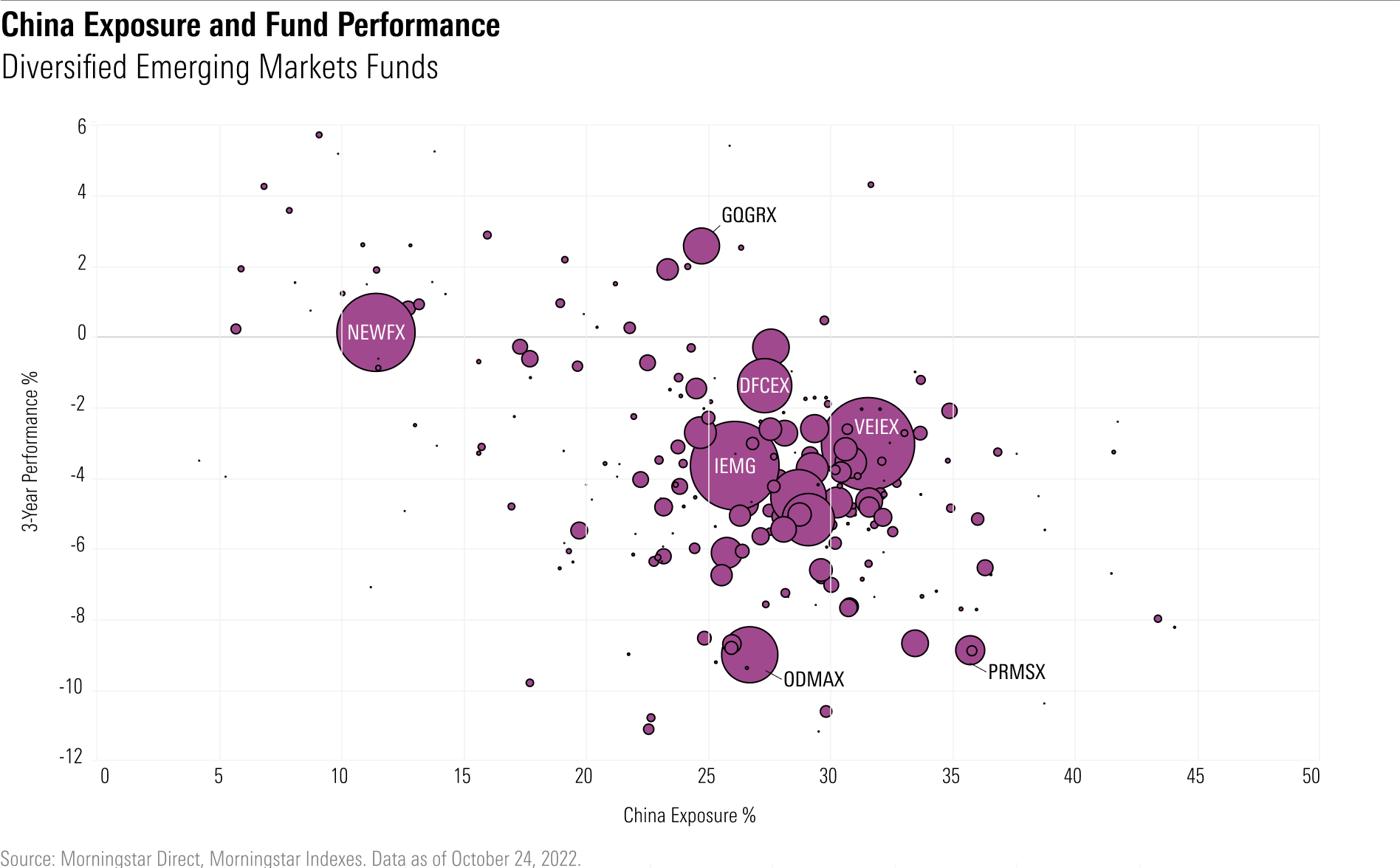

The Vanguard Emerging Markets Stock Index (VEIEX), the largest fund in the diversified emerging markets group with $61 billion in assets and a 31.5% exposure to China equities, fell 2.8% last week. And the iShares Core MSCI Emerging Markets ETF (IEMG)—which carries a 24.2% exposure to China and $56 billion in total fund assets—dropped 2.2%. Both funds are down over 26% for the calendar year.

What happened? The political reshuffle in China’s ruling Communist Party announced at its 20th party congress caused an outsize reaction in the markets, as it implies a more hard-line approach with the country’s zero-COVID program, more opaque future government policies, and greater uncertainty and risk.

Last week’s news is the latest in a string of what the founder of Life + Liberty Indexes and creator of the Freedom 100 Emerging Markets ETF (FRDM) Perth Tolle deems “autocracy risk,” described as risks resulting from government power that is concentrated in the hands of a few, with little democratic oversight.

"Investors are starting to look for the signs of autocracy risk and recognising them like never before," Tolle says.

"First, it was the market’s reaction to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine earlier this year. We’re seeing autocracy risks play out again in the latest market action surrounding China."

Tolle does not invest in China according to her fund’s screens for civil, political, and economic freedoms. For the year to date, the Morningstar China Index is down 40.3%, and the Morningstar Emerging Markets Index has fallen 27.1%. Since reaching its latest high in February 2021, the China index has lost 52.8%.

Political Risks in Emerging Markets

Autocracy risk can—in addition to limiting human freedom—stifle growth, prolong drawdowns, and promote capital flight. In China, trade restrictions and zero-COVID policies that shut down some of the country’s largest factories are other examples of autocracy risk.

“Investing in China has always been speculative,” says Tolle. “But now, investors are realizing that the country’s risks are greater than the potential outperformance they’ve been looking for.”

Tolle says that when outside investors buy China stocks, they don’t have insight into who owns the companies or what the accounting books look like.

“We can’t accurately calculate the risks we’re taking because we don’t know what’s going on in the background,” she says. “And sometimes, investors don’t benefit from the growth of these companies—the gains get siphoned off to government actors.”

And sometimes, autocracy risks can even render an investment’s value almost worthless overnight. Last year, the profitability of Chinese tutoring firms was placed at risk by a government order forcing all such companies to register as nonprofit organizations. Since January 2021, ADRs of TAL Education Group (TAL) have lost 93.9% of their value, while those of New Oriental Education & Technology Group (EDU) are down 86.7%.

"Increasingly, what you’ve been seeing over time is that the government of China is not hesitant to stick its hands in public companies’ positions," says Daniel Sotiroff, senior manager research analyst at Morningstar.

Sotiroff also points to the failed IPO of Ant Group—Jack Ma’s financial-technology company owned partially by Alibaba (BABA), set to be the largest IPO in history—as an example of government regulations affecting the markets. Just hours before the planned debut, Chinese regulators suspended the offering on the basis of new regulations.

Emerging-markets funds' hefty exposure to China makes them vulnerable to these and other autocracy risks. The Morningstar Emerging Markets Index—which measures the performance of stocks in countries with developing, often fast-growing economies—carries a 27.6% weighting in China stocks. Similarly, the diversified emerging-markets Morningstar Category for funds averages 28.8% exposure to China.

Over the trailing three years, the largest diversified emerging-markets funds, Vanguard Emerging Markets Stock Index and the iShares Core MSCI Emerging Markets ETF, have each lost about 10%, while the US market gained 33%.

Economic Growth May Not Equal Stock Performance

China’s economy has undergone a massive expansion over the past 30 years, but that growth hasn’t materialized into long-term returns for the country’s stock market.

"China has been the fastest-growing economy for years, by a long shot," Sotiroff says. Since 1992, China’s gross domestic product has risen from $426.9 billion to $17.7 trillion—that’s growth of over 4,000%. "And for a while, the stock market did grow, but it never really turned into great performance compared to other markets."

On an annualised basis, China stocks have returned 0.93% per year over the past 10 years as measured by the Morningstar China Index. At the same time, the Morningstar US Market Index has gained 12.6% over the past 10 years annualised.

Where is the Growth in Emerging Markets?

There are options for emerging-markets investors looking for growth and returns without autocracy risk, Tolle says, pointing to Chile, Poland, Taiwan, and South Korea as a few standout examples.

"There are many places to invest in emerging markets that have freer rule of law and better market protections,” Tolle says. "These countries will foster the growth stories of the future."

Correction: an earlier version of this article should have said that the growth of China’s GDP since 1992 was over 4,000%, not 984,411%