In the world of finance, we often think about decades-long investment time horizons.

In doing so, many of us have unconsciously trained ourselves to think long-term because that’s the nature of the job. This long-term planning mindset is something we can take for granted, but most people don’t think this way. That matters. A lot.

What iss Mental Time Horizon?

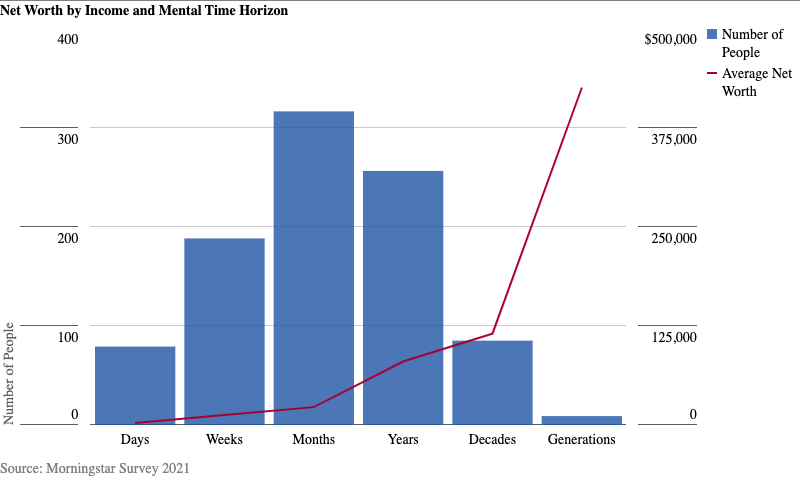

In a recent study for Morningstar, I asked a nationally representative sample of more than 900 US households the following question: "when you think about your finances, how far into the future do you tend to think and plan?"

I call this a person’s mental time horizon. It’s the point at which your mental picture of the future becomes fuzzy or unformed. Some can see only a few days ahead. Others look to the next generation. Innovators and entrepreneurs often think in generations or even millennia. The typical man on the street tends to think in the short term, however, as the results of our survey show.

In our sample most people, regardless of age, income, or education reported thinking several years ahead at most. This may explain why so many people struggle to save, invest, and adequately plan for the future. If you’re not even thinking about it, what motivation do you have to prepare?

Why Does It Matter?

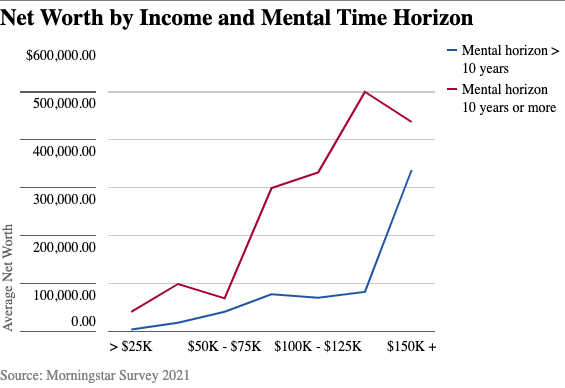

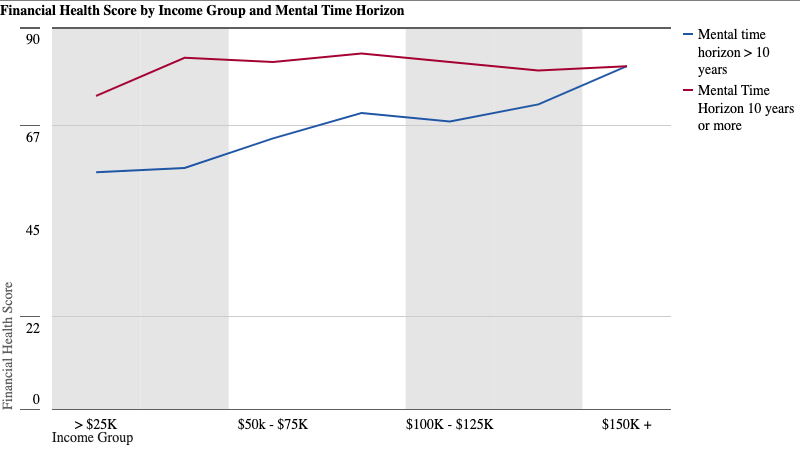

In our study we found that, in every income group, people who think at least 10 years ahead had saved significantly more than peers who had a shorter mental time horizon.

We saw a generally positive relationship between income and net worth, but in every income group, the average reported net worth was significantly higher among those with longer mental time horizons than those who reported thinking less than 10 years ahead.

The study also asked participants to complete a financial health survey created and validated by the Financial Health Network. (See the full FHN survey and methodology here.)

In every income group, people who said they think at least 10 years ahead had significantly higher financial health scores than their peers with shorter mental time horizons.

Linear regression showed that answers to this one question explained 27% of the variation in financial health scores (for comparison, income accounted for only 8% of the variance in financial health scores).

The Relationship is Likely Bidirectional

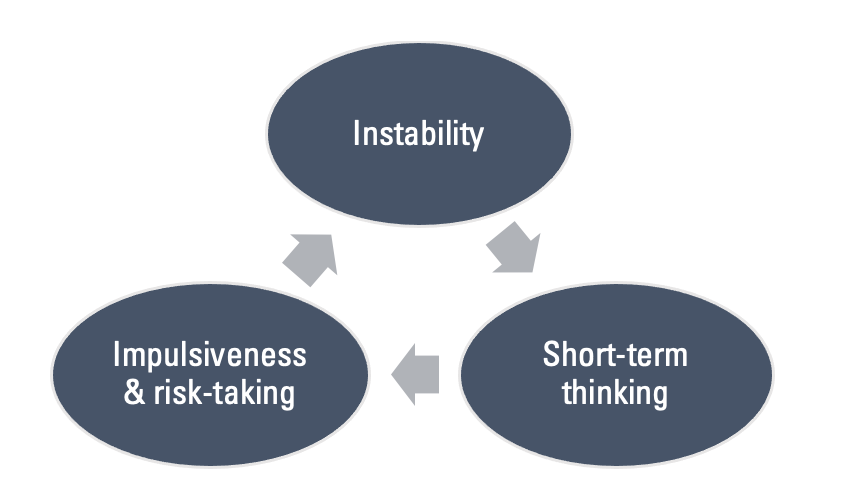

Which comes first: a high net worth or thinking about the future? It could be either one. For example, someone with more debt than assets may also have a high degree of instability in their life, financial or otherwise.

Instability makes it hard to look into the future because there is so much uncertainty. It’s very difficult to plan for 10 years out when you don’t know what will happen next week.

Unfortunately, short-term thinking can set us up for a poverty trap. Psychologists have found that short-term thinking is generally associated with more-impulsive, risk-taking behavior, and so those with a limited mental time horizon may make choices that exacerbate their financial insecurity, creating a negative feedback loop.