We all take water for granted. You turn on the tap, it’s there, you get a modest monthly bill and don't think too much about the inner workings of the industry, which in England was privatised in 1989.

Today, heatwaves, leaks, hosepipe bans and fears of rationing during the drought are part of the national conversation along with soaring energy bills. Low water levels in the Rhine in Germany suggest that this isn't a single-country issue.

Environmental damage has also become a concern, with untreated sewage released into English rivers for 2.7 million hours in 2021*. Not surprisingly, with the public mood turning, there are now calls to nationalise the industry, although opposition party Labour is now rowing back on 2019 plans to bring energy, rail and water into public hands.

What does all this mean for investors, who have become used to water stocks being dull, dependable income payers? A low-risk industry has suddenly become medium- or high-risk in a matter of months.

Let’s have a quick look at the water industry and why it differs from energy, which everyone is focused on. The UK is self-sufficient in water, which means we don’t have to import it from dubious regimes, and the price of water doesn’t fluctuate on global markets.

From a pricing point of view, the industry is very tightly regulated, and consumers’ bills are orders of magnitude lower than energy bills (which are forecast to hit nearly £5,000 this year). But supply does fluctuate according to rainfall, meaning that – as customers are discovering this summer – constant flow of H2O in our homes cannot be taken for granted.

Your local water company may be private. The largest, Thames Water, has shareholders and pays dividends, but retail investors can’t buy shares in it. But a handful of water/sewerage companies are listed on the London Stock Exchange and they include Severn Trent (SVT) and United Utilities (UU). So the investment universe for UK shareholders is relatively small, although this expands if you take in Europe: France’s Veolia Environnement (VIE), which operates in the UK too, is the world’s largest water company. On the ETF side, iShares Global Water (DH20) is rated Silver by Morningstar analysts and its top holding is American Water Works (AWK), which has a 2-star rating.

Upgrade Bill

A common theme in Morningstar analyst reports is the costs that companies must bear to pay for new pipes and other products.

"Much of Britain's water infrastructure is more than 200 years old and could require major upgrades during the next decade," says Tancrede Fulop in his assessment of United Utilities.

The company is due to spend £500 million a year on this in the next five years, he adds. But Andrew Bischof, who covers American Water Works for Morningstar, says there’s an upside to these upgrades: infrastructure becomes more efficient and easier to maintain. So there are heavy costs implied in the industry, but these are necessary to avoid leakages (which have blighted the UK) and improve security of supply – a key issue in the energy industry too.

From an ESG point of view, just because the water industry isn’t as volatile or politically fraught as energy, but it feels like the world can longer be complacent about any natural resources. In the US, water has become a tradeable commodity linked to prices in California, which has been at the sharp end of climate change, suffering from heat, wildfire and drought. Water scarcity is a global issue and one that is likely to intensify, particularly in emerging markets. My Sustainalytics colleague Kate Matrosova has looked at this issue in depth in her article “It’s Time to Start Talking Water Risk”.

Setting morality aside, can investors tap into this shift in perception from plenty to shortages? Scarcity is the basis of many investment thesis, from property, Bitcoin and commodities. Those who bought into oil stocks when crude was briefly at $20 a barrel have been handsomely rewarded. But investors reallly look at water from an impact rather than a scarcity perspective. ESG rules take water into account as part of the “E” for environment, plus there’s an argument that it falls under the “S” in terms of social impact: it’s hard to feel good about yourself as a human being if you’re profiting when people in sub-Sahara are dying of thirst, for example.

More specifically, under the EU’s Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), companies are judged by their water usage and whether this creates pollution or hazardous waste. Many ESG funds hold companies that work to improve access to water in poorer countries, and that involves improving infrastructure such as pipes.

Praying for Rain

From a UK perspective, a rainy autumn and winter are likely to refill the reservoirs and keep shortages at bay. That’s likely to cool public anger until next year at least.

The threat of nationalisation looks low – also on the grounds that the energy crisis is going to become the all-consuming issue for a new prime minister. Still, with Scotland and Wales water companies in public ownership, these are likely to provide unflattering comparisons with England's privatised market in future years.

In terms of bills, these are unlikely to spiral and make the headlines. While Ofgem is reviewing its cap quarterly, water regulator Ofwat’s regulatory cycle is longer, with the next review due in 2025.

Morningstar’s Fulop explains that while rates do increase with inflation, the regulator doesn’t allow companies to just pass on chunky input costs to customers.

"Regulated rates require companies to cut costs annually to hit targets, and the last five-year regulatory review was harsh," he says.

In terms of dividends, UK water companies have solid if unspectacular yields. But with supply issues coming to the fore, close attention is being paid to dividends and executive pay. The issue may go away temporarily, but climate change is likely to keep the pressure on UK water firms in summers to come.

As stockbroker IG puts it, "privatisation may have put a vital commodity into the hands of profiteering business, but it has also provided greater investment and a faster pace of development." Can you have one without the other? Water customers may be clamouring for change if they can't fill up the kettle.

*Environment Agency data

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6BCTH5O2DVGYHBA4UDPCFNXA7M.png) Is ESG Dead? Perception Looks Different From Reality

Is ESG Dead? Perception Looks Different From Reality

Pay Practices at Big Oil and Gas Companies Fail to Drive Decarbonization

Pay Practices at Big Oil and Gas Companies Fail to Drive Decarbonization

Are FTSE Mining Companies Cheap Right Now?

Are FTSE Mining Companies Cheap Right Now?

Advice for George Osborne and Stock Market Regrets

Advice for George Osborne and Stock Market Regrets

How to Find Solid Dividend-Paying Stocks

How to Find Solid Dividend-Paying Stocks

10 Top-Performing Funds in the UK

10 Top-Performing Funds in the UK

Fund Research: Europe’s Shining Stars

Fund Research: Europe’s Shining Stars

3 US Dividend Stocks for March 2025

3 US Dividend Stocks for March 2025

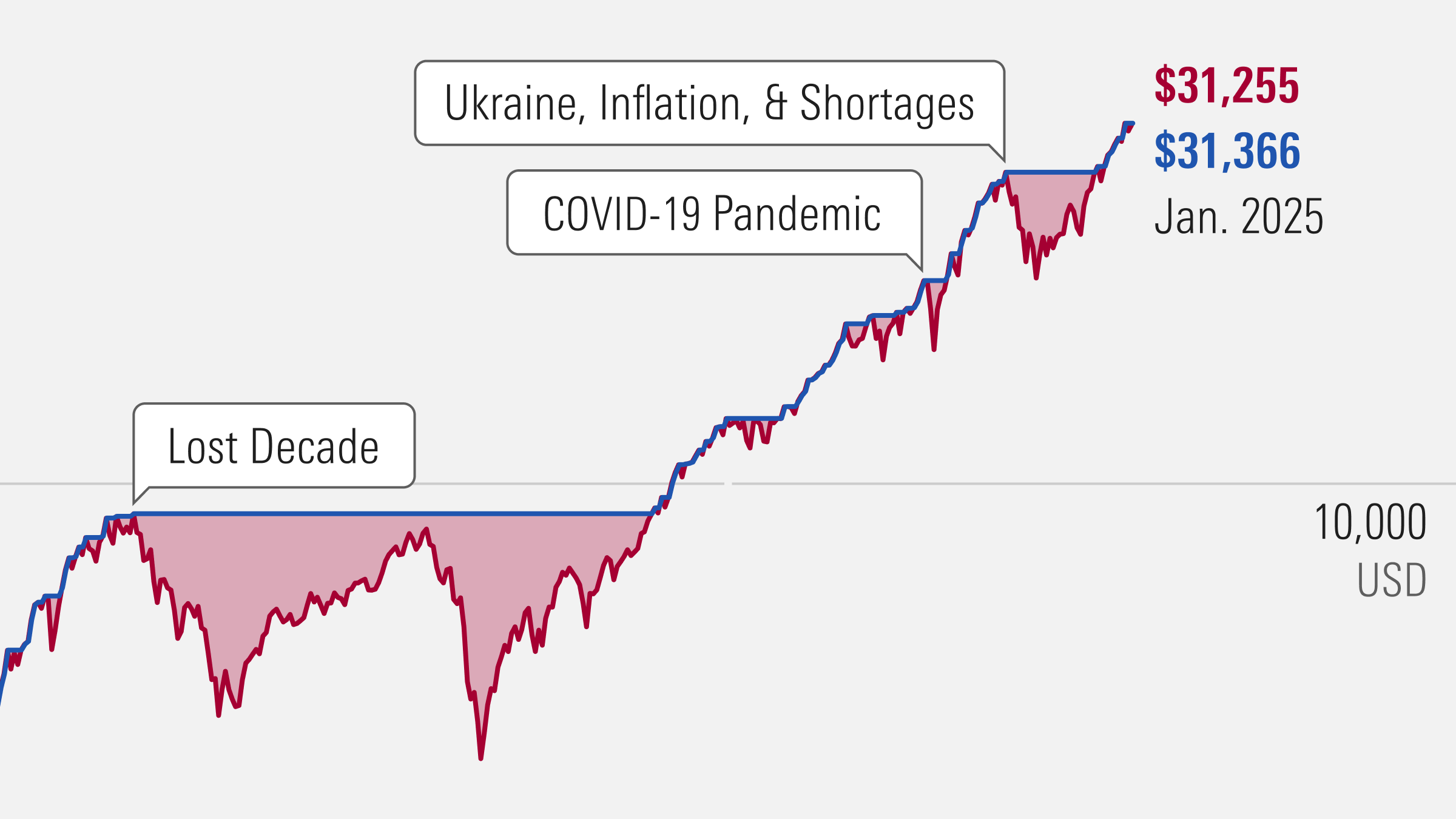

What We’ve Learned From 150 Years of Stock Market Crashes

What We’ve Learned From 150 Years of Stock Market Crashes

US Job Growth Holds for Now, Fed Rate Cuts Still on Pause

US Job Growth Holds for Now, Fed Rate Cuts Still on Pause

Aberdeen Rebrand Cements ‘Cautiously Optimistic’ Analyst View

Aberdeen Rebrand Cements ‘Cautiously Optimistic’ Analyst View

The Worst-Performing ETFs of the Month

The Worst-Performing ETFs of the Month