Capitulation in investing is very similar to capitulation anywhere else – it is a situation in which investors feel extreme pressure to sell, and then do so in droves. Other ways to explain it include surrender. Throwing in the towel. Giving up. Waving the white flag. Selling it all and running away.

Capitulation Leads to Market Sell-Off

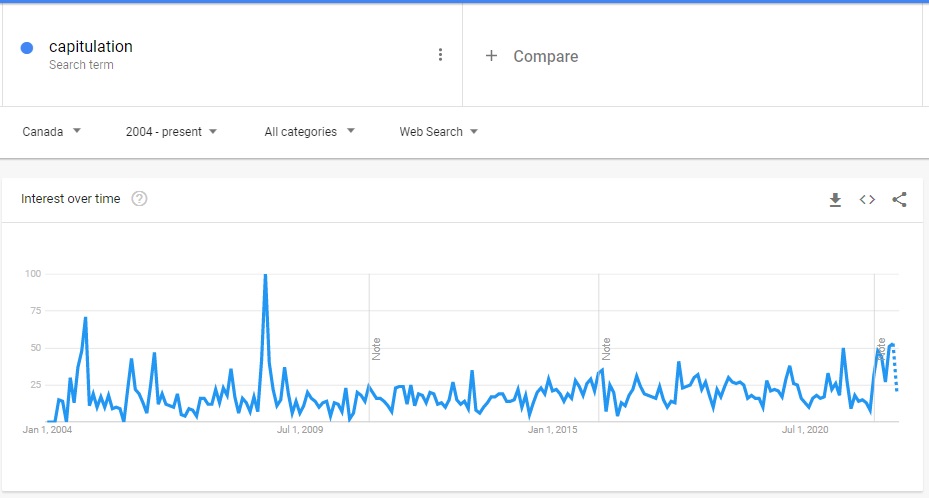

The term "Capitulation" has been around for a while, but according to Google Trends, it was most popular in - surprise, surprise - September and October of 2008.

Simply put, capitulation is the slippery slope that starts when the market (or stock or stocks) starts going down and continues to fall for some time. The idea of capitulation is that at this point, even as some investors stay bullish, a majority panic, and when the losses become too much to bear, they capitulate, selling their holdings, which in turn leads to an even steeper fall in prices, which then leads to a relief rally.

As you can imagine, one of the indicators of a capitulation is very heavy trading volume, which gets rid of investors with lower risk appetite, leaving only ”Diamond Hands.” Urban Dictionary defines "diamond hands" as fortitude in continuing to hold an extremely risky financial position. This fortitude may take the form of either refusing to sell a badly losing position (waiting for it to recover while risking even larger losses) or refusing to sell a highly profitable position (waiting for even greater gains while risking the loss of earlier gains).

Capitulation is also the point at which market participants believe that the bottom has been reached. If you can precisely pick this moment and buy the market (or the stock that is falling) at this exact point, you could end up making a killing, because from this point on, the market or stock(s) has nowhere to go but up.

It’s Impossible to Identify Capitulation

It’s easy to call the bottom of market, but next to impossible to actually predict it. The bottom of a stock dip is rarely marked by investors panicking and selling en masse (unless, of course, there is a specific news event that triggers this mass exodus.) Most of the time, stocks quietly bottom gradually over time, sometimes over the course of hours, at other times over the course of days or even months. Oftentimes, investors might not even notice that the bottom has been reached before the stock(s) or market starts to recover.

Think about Gamestop Stock (GME) before January 2021. Would you have been able to call the exact bottom for the stock contemporaneously? It’s doubtful. Neither would anyone else. Capitulation can be observed only in hindsight. Aside: Another indicator of a capitulation (albeit one that has already taken place) is a rebound in price that follows once the panic selling has run its course.

As Jason Zweig said in the Wall Street Journal back in 2008, “Bear markets sometimes end with a bang, sometimes with a whimper. You're more likely to see a unicorn in your backyard or a chimera in your kitchen than you are to spot an indisputable sign of market capitulation. …Don't kid yourself into thinking that you will ever get a clear signal out of such an unclear indicator.”

In fact, long-term investors who have a plan would be best advised to ignore capitulation altogether. The best thing to do is stick to your plan.

Why Do People (and Investors) Capitulate?

According to Morningstar behavioural researcher Samantha Lamas, There are many possible culprits of panic selling when it comes to behavioural biases. “One that comes to mind for me is recency bias. When we predict what’s going to happen in the future, our minds naturally reach for what happened most recently. In part, that is because our brains have an easier time remembering what just happened versus what occurred further in the past. Although this shortcut usually works out for us in everyday life, it can result in us placing undue importance on recent events when we make investing decisions. For many investors, this means that when their portfolio drops 10%, recency bias convinces them that it will continue dropping.

How to Guard Against It?

According to Lamas, a person that may be in danger of panic selling may be constantly calling their advisor at every turn of the market, or just constantly checking their portfolio or market news.

To guard against panic selling, Lamas says investors can do a few things.

- Start with creating a schedule for how often you check the market news or your portfolio, so that the constant fluctuations don’t impede your good judgment.

- Have a plan for what to do in case the market falls – or rises.

- Create selling rules of thumb, something like “I will always run a new trade idea by my close friend or family member before hitting sell.”

“This final rule introduces some friction into the decision, and hopefully helps the person think twice before making a rash decision,” Lamas says.

When Should I Sell My Stocks?

As Morningstar’s Christine Benz points out, you don’t have to be an investment legend to know that it’s rarely wise to be a seller in such environments if you can avoid it. “Attempting to cash out during a market sell off violates one of the key tenets of successful investing: selling high. And investors who panic-sell are prone to make emotional decisions that undermine the success of their plans. Even the emotional relief that selling might bring is fleeting, as it’s so often quickly replaced by another nagging worry: Is it time to get back in?” she says.

For some investors, though, it might make sense to sell stocks in three cases, Benz says. Here are her three scenarios:

- You’re getting close to retirement and need to de-risk: Even as our comfort level with risk-taking usually grows as we get our sea legs as investors, our plans’ ability to absorb risk usually diminishes. Even as risk tolerance grows with experience, risk capacity--the ability to absorb big losses in our equity portfolios--declines as we get close to drawing from our portfolios. At that life stage, it’s wise to begin building out positions in cash and bonds as a bulwark.

- You have a short-term investment goal: If you are a younger investor, chances are you have big lifetime milestones coming up within the next few years, such as buying a home or having a baby. In such situations, you may need to tap your portfolios to cover an emergency expense, cover during periods of reduced (or no) income, or to fund some shorter-term, nonretirement goal like a house down payment. New investors who find themselves with too risky portfolios should feel absolutely no shame in liquidating some of their equity holdings in favor of a portfolio mix that adequately reflects their potential need for liquid assets within the next few years.

There’s a chance you’ll capitulate if things get worse: the preceding two situations relate to risk capacity, where a too-aggressive portfolio might be at odds with someone’s spending horizon. But even if an investor has an adequately long time horizon to hold stocks, there’s another issue that can crop up with too-risky portfolios, and that’s capitulation risk.

That’s my own term, referring to the chance that the investor could become so nervous during periods of losses that he sells himself out of stocks, thereby turning paper losses into real ones. While throwing stocks overboard won’t make sense, lightening up on stocks while adding a bit more to bonds and cash just might. In addition, nervous investors can take a closer look at the complexion of their equity portfolios, making sure they have a balance between value and growth stocks and hold some non-local country stocks. (Read more about home country bias here.)

.jpg)