Inflation has now hit a 40-year high of 9%, and is expected to hit 10% this year.

Reaching double digits this summer seems like a significant milestone, and one that would take us back to the 1970s*, an era remembered unfondly by people of a certain age who associate the period with endless union strikes and piles of rubbish in the streets.

Anything close to a repeat of the situation would pile more pressure on the Bank of England – and UK government – to "act" to solve the cost of living increases, even though most of the inflationary pressures are global.

For its part, The Bank of England is starting to resemble the bystanders in the opening scene of Ian McEwan’s Enduring Love, who watch the balloon go ever higher and become increasingly frantic about bringing it down.

Can inflation really be brought down to earth with conventional monetary tools? Or is it just a case of leave it alone and wait and see?

May 2022 MPC Meeting

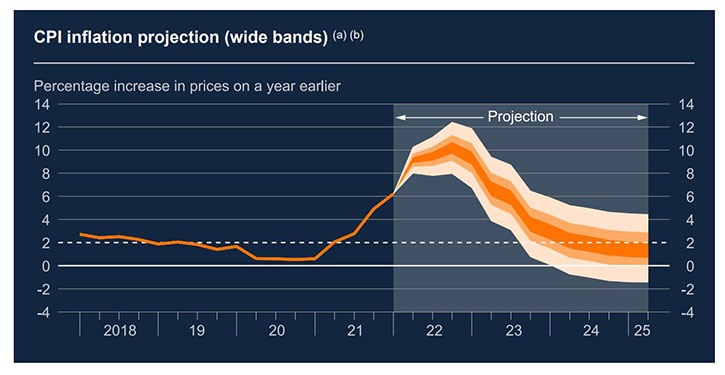

The Bank of England's quarterly charts give an idea of where it thinks various economic phenomena are heading. It looks 13 quarters ahead, but builds in parameters of uncertainty in the form of fan charts (see above).

In its notes to the charts, the BoE says:

"There are considerable uncertainties surrounding the projections of CPI inflation, unemployment and GDP growth published. This uncertainty is reflected by the presentation of projections as fan charts. The fan chart shows the Committee's view of the uncertainty at specific points during the forecast period."

Inflation worriers can surmise the following: in extremis, CPI inflation could hit 12% this year. But the chart shows a reassuring and rapid fall back to 2%, which all too conveniently just happens to be the Bank’s inflation target. That was set in December 2003 (on a CPI measure).

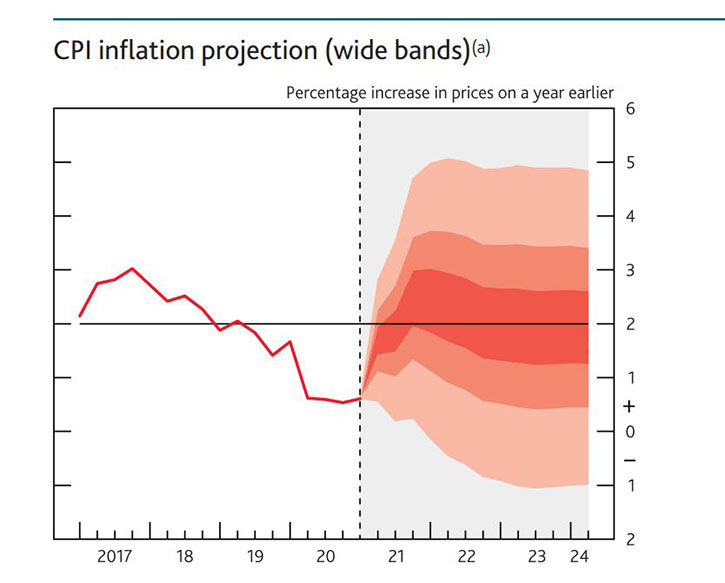

Let’s compare the above chart to the one produced exactly a year ago (see below from May 2021).

In this chart, the numbers are different – completely different. CPI doesn't even hit 5% in the most hawkish scenario. And the shape is different too.

So why does the Bank of England’s expect inflation to fall to target next year? In the "plain English" version of its May monetary policy report, the Bank revisited some of the arguments used by "team transitory", before some of the scary inflation prints started to roll in. Supply chain issues will be resolved, it predicts, and falling demand (as the economy slows) will take some of the heat out of the economy.

"We don’t expect the causes of the current high rate of inflation to persist," it says.

"It’s unlikely that the prices of energy and imported goods will continue to rise as rapidly as they have done recently. We also don’t think that the demand for goods will continue to rise as fast, and we expect that some of the production difficulties businesses are facing will ease. We expect inflation will be close to our target in around two years."

Of all the assumptions here, the suggestion that energy prices (which are one of the biggest drivers of the world's inflation shock) will drop back so neatly is the most controversial.

Much depends on Russian supplies of natural gas to Europe, and the status of the Ukraine war. A cold winter in 2022-2023 could really expose the frailties of our energy complex, which hasn’t had time to adjust to the new world order ushered in on February 24 this year. In the UK, Ofgem will review its energy cap again in October, having initially done so in April, a move that led to a spike in prices.

Still, away from the headline figure, there could be signs inflation is starting to ease already. Ed Smith, co-chief investment officer at Rathbones, detects signs of decreases in so-called "core inflation", which strips out energy and food costs because they are so volatile.

"Plenty of inflation pressures are still broadening in some sectors, but inflation in others, particularly core goods, is easing significantly," he says.

"The next few months are going to be crucial, but a return of durable goods [like cars and furniture] inflation from very high rates to more normal/negligible rates is crucial for the current inflationary episode ultimately proving transitory.”

Of course, food and energy inflation tends to hit the poorest hardest, as they are things people cannot avoid paying for.

What Do Interest Rates do?

Central bankers haven’t faced inflation like this for many decades. They have had multiple crises to address, like Brexit, the pandemic and now war, but their answer has largely been to cut rates and increase quantitative easing to flood the economy with money.

Slashing interest rates may have helped cushion the blow from the financial crisis – and the 2020 pandemic – but it now seems less effective on the other side.

Don't be fooled though. The Bank of England makes the link between rates and inflation seem simpler than in real life.

“The main tool we use to bring inflation down is to increase interest rates," it says.

"Higher interest rates make it more expensive for people to borrow money and encourage them to save. That means that, overall, they will tend to spend less. If people on the whole spend less on goods and services, prices will tend to rise more slowly. That lowers the rate of inflation."

Interest rates were raised to 1% in May 2022. Even assuming they will rise further this year, we could have CPI at 10% or more and base rates at 1%. Interest rates are not expected to get anywhere near CPI of course, and that would no doubt be counterproductive: the last time rates were that high was in the early 1990s, a recessionary period that saw mass job losses and home repossessions. (The base rate was raised to 14.88% in October 1989.)

Policymakers know that rates that high would likely trigger the implosion of the consumer economy, which is built on cheap car loans, mortgages, and credit cards. And a chart of longer-term interest rates shows that, while we’re in scary territory, we’re a long way off the 1970s, when RPI hit nearly 27% – and indeed, in 1980, when it pushed above 20% before tumbling in the rest of that decade.

Big Data Meets the Future

What can we learn from this inflation scare? One is that economic forecasting is a perilous task and investors probably can’t depend upon forward-looking predictions when they make decisions. Data is multiplying every year, but still struggles to make the future add up.

The other lesson could be that we expect too much of institutions like the Bank of England to control our destinies via something as blunt as a base rate change. Fiscal and monetary policy combined forcefully to "kitchen sink" the Covid-19 response but that could be a rarity. We don’t know when that inflation balloon is coming down, but perhaps we should be grateful that gravity will eventually win, even if it takes a recession for it to happen.

Finally, it’s worth pointing out that the UK has changed its official inflation measure in the last few decades. The ONS prefers the CPIH measure, which includes owner occupier housing costs. This was 7.8% in April, lower than the 9% figure reported in the media. RPI, which is no longer used as the preferred inflation measure, is already over 11%. I last looked at this issue of what’s in the inflation in “The Great Inflation Overhaul”.

- The Bank of England started explicitly targeting inflation in 1998 after it was made independent.