You can accomplish a lot in 24 hours. If you’re feeling ambitious, you might kayak 231 miles, cycle from Miami to Key West (a 160 mile trek), or, (if you’re Aleksandr Sorokin of Lithuania) break the world record for running the furthest distance in 24 hours (a staggering 192 miles).

On the more pedestrian side, there’s one thing you can do that’s even easier, and it may just end up in the history books anyway: start a business.

This is actually one of the things that makes the UK pretty impressive. While postal applications to Companies House can take up to 10 days to be processed, setting up a company via its portal can take less than a day. Internationally, it's harder.

According to 2019 data from the World Bank, starting a business in Poland incurs a 37-day wait; cracking Cambodia takes a restlessness-inducing 99 days; while entrepreneurs in Venezuela are looking at 230 days of navel gazing to get their paperwork through: that’s nearly two thirds of a year.

At a point in time characterised by widespread mistrust of government statements, then, one might say the Department for International Trade’s claims about the UK’s business culture are at least reasonably accurate.

“The UK has a mature, high-spending consumer market and an open, liberal economy, world-class talent and a business-friendly regulatory environment,” it says.

“Our language, legal system, funding environment, time zone and lack of red tape helps make the UK one of the easiest markets to set-up, scale and grow a business.”

Start Me Up

In some ways, it’s little wonder the government’s trade-conscious departments are courting start-ups. The pandemic has fuelled a boom in the number of new businesses, and, as certain treasury ministers have been keen to point out, supporting the businesses of the future will require a new framework that accommodates – among other things – new payment methods.

Step forward the cryptocurrency conundrum, which, as Morningstar senior editor James Gard explores this week, has come in from the cold as Rishi Sunak’s new best friend amid a politically-driven regulatory scramble for new talent to police the sector.

Try as he might celebrate “British” innovation and its relationship with new technologies, though, making the UK an attractive place to invest is easier said than done.

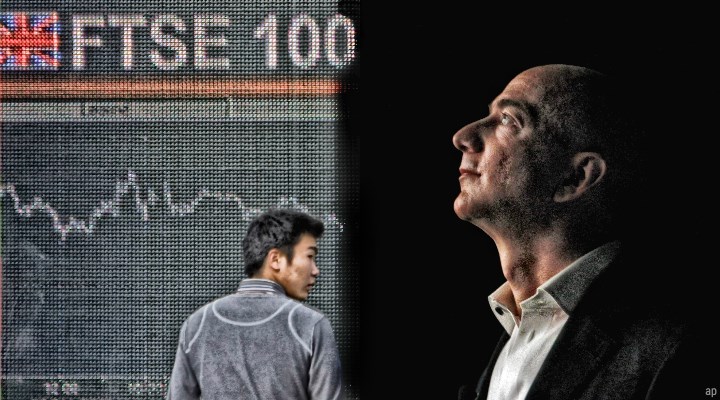

For all the nimble paperwork processing, promising fintech start-ups and business-friendly politicians, there are dozens of big UK brands whose collective image is even more pedestrian than your attempt at that record-breaking run. A five-year look at the FTSE 100 doesn’t exactly knock your socks off. The desperation for a headline-grabbing IPO (or four) is real. It’s an issue bugging politicians and investors alike.

The Next Big Thing

UK IPOs have hardly been the stuff of legend of late. They are not the whole issue by any means, but they are a good measure of sentiment.

After its rocky flotation in April last year, Deliveroo’s (ROO) shares are still 72% below their IPO price. The story at The Hut Group (THG) is even worse, with shares down 75% since the float price of 500p. Its stock could now be a bargain, but the flat-ish line on the graph seems to suggest few people are buying. CEO Matthew Moulding has reportedly even mulled taking the business private, a sentiment that seems to suggest not a few regrets under his roof. Plenty of people have asked why the UK lacks an Amazon-style success story.

The truth is that things like Amazon didn’t happen overnight. By the same token, nor does the kind of deep-seated structural change needed to make the UK a more attractive place to do business. Big businesses know this. Some might argue they are too hooked on paying dividends to income-obsessed investors. A spate of share buy backs in the last year has also made onlookers wonder whether they are spending their money on the right things.

Others see no solution without government input. The Confederation of British Industry (CBI) published an action plan last year, urging the UK’s politicians to employ smarter taxation to reward businesses that invest. It also highlighted the need for major infrastructure projects, and a reform of the apprenticeship levy.

Shrouding all of this is the elephant in the room: net zero, which poses as much of a problem as it does an opportunity. For its part, the CBI argues there is no green future without taxation reform anyway.

"One food retailer told us how they’d had to pause ambitions to fit Solar PV tech across their outlets, because fitting it in seven stores initially led to such a huge rise in their business rates bill that it made their long-term plans less viable," CBI director general Tony Danker told Manchester’s Alliance Business School last year.

"Let’s end this absurd disincentive to make our buildings more energy efficient."

In the final analysis, what this poses is a tricky re-imagining of the relationship between the state and business, but also businesses and their investors. And the clock is ticking. In the wake of Brexit, it will take less than a day for investors to discern the difference between chest-thumping patriotism and practical decisions. And decisions are arguably overdue.