This article was originally published on Morningstar.co.uk on 8 April, and has been repurposed as part of our Earth Day coverage

I can barely believe it myself. Lately, we’ve been hit with a year’s worth of headlines in just weeks. The biggest is the war in Ukraine. In just days, new paradigms have been born. A re-assessment of just about everything is underway.

Among them, a reconsideration of whether arms stocks are actually a good thing to include in ESG portfolios after all. I have penned my views about that already. What I’d like to do is reflect on a broader point.

A Hale of Bullets

In a well-written (and well-worth-reading) column this week, my colleague Jon Hale took ESG’s critics to task. Railing against the editorial line taken by the Wall Street Journal once more, Hale had more than a few words for those who believe the war has exposed ESG’s core failings.

“They seem to think sustainable investing is dogmatic, monolithic, and undifferentiated,” Hale said of the situation.

What follows is a masterful state of the nation-style unpacking of how ESG actually works.

Far from being inflexible, he argued, ESG is a big church with a diverse congregation. Many ESG funds do have some exposure to arms companies, he showed. Indeed, how could they not, given the scale and variety of product lines offered by the big players.

And so it is too with oil. You’ll find oil majors in ESG funds sometimes, as they do play some part in funding the climate transition. That’s being kind, of course, but to digress would be to venture into a different column altogether.

As I reflect on my concerns about that, though, I worry I am being too idealistic. ESG may be a distinct tranche of capitalism, but born of capitalism it certainly is. As you would therefore expect, it is not realistic to demand that it be perfect, or predictable. It is a product of market forces, and market forces have a mind of their own. It barely needs saying consumer choice is also important.

That said, I am getting nervy. Nervy about how broad the church is, and who is allowed in. To take you back to before the invasion, in October 2021 Morningstar published a report showing the “universe” of global sustainable funds had grown by a staggering 51% in the third quarter of the year alone. I greet news like that with profound concern. Are we going for quantity over quality here?

To that end, I agree with Hale to some extent, but from a different angle.

I’m sure the WSJ is wrong, as he says, but I think for different reasons. Financial publications can feel free to take issue with ESG being “undifferentiated” and even “monolithic”, but the dogma bit is important, nay, a good thing. ESG should be opinionated and exclusive. Where else in financial services is there such an arena for investors to make their views known on a range of companies and issues?

But to issues, and to where I began.

As the world absorbed news of the war crimes taking place in Ukraine, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was issuing its latest extremely worrying report on climate change.

In what could be received as a final warning on the inevitability of an impending climate crisis, the IPCC said extreme steps would be needed to avert a catastrophe. Alongside ditching fossil fuels like coal and oil, consumers are going to have limit their usage of resources. That means low-carbon diets, “greener” urban areas, and travelling less.

But that all sounds very “peaceful” doesn’t it?

You might argue it is much easier to fight climate change with peaceful consensus and co-operation, and in principle I agree. That might make arms and ESG necessary bedfellows to ensure conflicts end quickly and restore what is increasingly termed “national security”. But it’s a bit wishy-washy.

The more complicated reality is that, whether operational in anger or not, war machines are bad for the environment.

For its part, the US military has been estimated to produce more carbon emissions than entire countries, and, since the start of the war on terror in 2001, it is supposed to have emitted 1.2 billion metric tonnes of greenhouse gas. On the ground, the armoured wagon Humvee fetches between four and eight miles per gallon. Even on exercise, nobody is thinking about greenhouse gasses. The latest military technology has for years focussed on armour and modularity. Batteries are a very new thing.

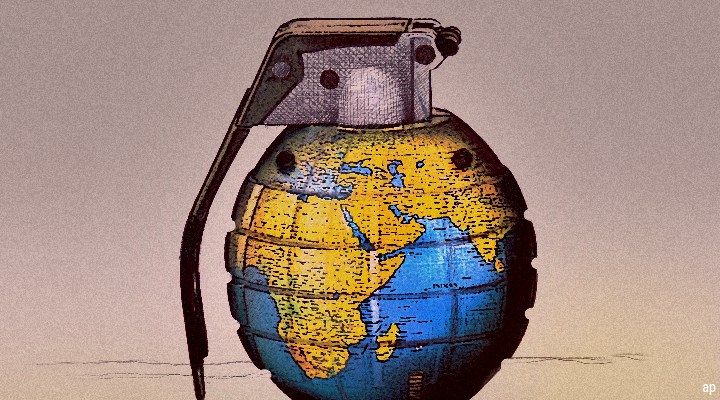

But not even that is the central point. Forget war causing climate change, climate change causes war. Populations scrambling for resources inevitably causes conflict. A 2019 paper estimates climate change or “climate variability” has influenced between 3% and 20% of armed conflict risk over the last century. That’s a big spread for sure, but it should be more central in our minds. ESG certainly shouldn't be assisting it as a phenomenon.

Not at Ease

This is a convenient moment (if you can use such a phrase), then, to re-assess ESG. To some degree, I do feel wary of welcoming yet more red tape to financial services, knowing as we do that it can have grave unintended consequences. But with ESG it is essential.

On the demand side, it’s important that clients understand what they’re investing in, for sure. I want to know if my climate fund has oil majors in it. But the supply side is just as – if not more – important. The bar for what constitutes ESG is frankly far too low.

As such, what sounds like a principled approach to pivoting finance towards practical solutions in the form of ESG has proven fickle (and vague). The disappearance of the fragile consensus established by COP26 from our consciousness (and consciences) is evidence enough. All it took was a conflict on NATO’s borders for people (and governments) to decide ESG is actually about something completely different.

And on the topic of money, a final reflection. The IPCC had an uncomfortable reminder for those at ease with the idea investors can have their cake and eat it too. The wealthiest are among those to blame for the planet’s travails. Great if you get rich from investing, and even better if you do it via ESG, but that is not the end of the story. How you deploy those gains is crucial.

"Wealthy individuals contribute disproportionately to higher emissions but they have a high potential for emissions reductions, whilst maintaining high levels of well-being and a decent living standard," IPCC report author Professor Patrick Devine-Wright said.

“I think there are individuals with high socioeconomic status who are capable of reducing their emissions by becoming role models of low carbon lifestyles, by choosing to invest in low carbon businesses and opportunities, and by lobbying for stringent climate policies.”

So, as I await the response that “nothing is simple, it’s not that easy” I’m ready to respond with precisely those words. The idealistic notion that ESG is a broad church with many members is lovely, but the practical implications of that approach for the climate are less rosy. Call it a grenade that really is worth throwing back.

Ollie Smith is UK Editor at Morningstar. If you’re keen to participate in the new editorial initiative for readers to meet over Zoom and discuss what matters to them in finance and investing, contact him at Ollie.Smith@morningstar.com

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6BCTH5O2DVGYHBA4UDPCFNXA7M.png)