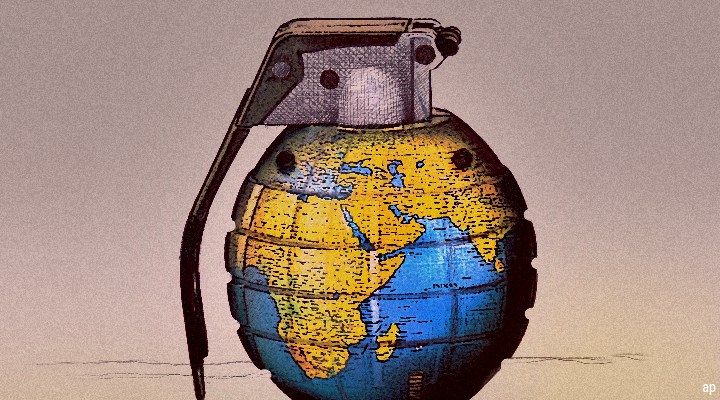

From pretty much the moment Russia invaded Ukraine, its war in the country has been held up as an example of "fundamental flaws" in sustainable investing.

Denunciations have claimed sustainable funds eschew military contractors and fossil fuels at a time the world most needs them. Such critiques are sloppy and unsupported by data.

For starters, most critics don't know what sustainable investing even is. For the most part, their claims reflect a total lack of understanding of the diversity of the field. They seem to think sustainable investing is dogmatic, monolithic, and undifferentiated.

What they don't understand is that sustainable investing is a big tent, addressing a spectrum of investor concerns and preferences. Yes, like all funds, sustainable funds seek to deliver competitive investment results. They are different because they have the additional objective of seeking to deliver positive environmental, social, and corporate governance outcomes.

In pursuing these twin objectives, sustainable investments employ a range of approaches, as we've described in the Morningstar Sustainable-Investing Framework. Those choices reflect different philosophies and different takes on many issues. What these approaches have in common is that they seek to attract end investors who want their investments to align with their concerns.

Defence Weaponised

The first supposed flaw raised by the war is that it calls into question sustainable investors' avoidance of military contractors and manufacturers of controversial weapons like vacuum bombs.

"If you don't have security and stability, if you can't defend the open values of democracies, you cannot have any kind of sustainability," said Jan Pie, a European defence industry lobbyist, in the early days of the invasion.

Pie wasn't really making an altruistic point here; he was playing politics, using the war as a convenient talking point to lobby European Union regulators to include the defence industry as a socially beneficial activity in its sustainable investing taxonomy.

Unfortunately, this claim was repeated in The Wall Street Journal this week, leading the paper to conclude it represents a "fundamental flaw" of sustainable investing. But there is no blanket avoidance of military contractors among sustainable funds.

According to Morningstar Direct, among such funds globally, fewer than one in four (23%) have a stated policy of excluding military contractors. And 44% of sustainable funds have some exposure to military contractors in their most recent portfolios. That’s not so different to other funds, 60% of which have some exposure to military contractors. (Most funds have very small exposures to the industry, as many military contractors are large companies with other lines of business.)

Rather than outright exclusion of military contractors, most sustainable funds subject them to the same kind of ESG risk analysis that they use for other companies. As you might guess, military contractors tend to have high ESG risk assessments, which contributes to exposure being somewhat lower among sustainable funds than other funds.

Sustainable investing is not an anti-defence-industry monolith. Investors who want to avoid military contractors can easily find funds that allow them to do so. Those who don't can find many sustainable options that focus on other dimensions of sustainability. There are all kinds of routes an investment can take to fulfil its goal of providing competitive investment results along with positive ESG outcomes.

White Phosphorous, Red Flag

One thing Ukraine doesn't need is either side using controversial weapons, yet the same Wall Street Journal article suggested the avoidance of controversial weapons is another example of a fundamental flaw in sustainable investing.

Hardly. While specific definitions vary, according to Sustainalytics, controversial weapons are those that have a severe, disproportionate, and indiscriminate impact on civilian populations, sometimes even years after a conflict has ended. They include: antipersonnel mines; nuclear weapons; cluster weapons; biological and chemical weapons; depleted uranium; and white phosphorus munitions (including white phosphorous grenades deployed as anti-personnel devices). Does anyone believe these types of weapons should be used in the defence of Ukraine? Ten countries prohibit investments in companies involved in the production of such devices.

Thus, even if all sustainable funds excluded controversial weapons, the war does not expose flaws in that stance. It's also important to note not all sustainable funds have a stated policy of excluding controversial weapons. To be sure, they are closer to a consensus around controversial weapons than they are around military contracting in general: two thirds of sustainable funds exclude controversial weapons. And 79% of sustainable funds have no exposure to companies that make controversial weapons. Among conventional funds, 49% have no controversial-weapons exposure. (The actual level of exposure in the vast majority of funds is small.)

Fossil Fuel-Free

Finally, there is the claim that the war exposes the flaw in sustainable investing's avoidance of fossil fuels and support for renewable energy. With sanctions on Russia, and parts of Europe still dependent on Russian natural gas, more fossil fuel production is necessary, not less – or so the argument goes.

Of course, most sustainable investors would argue the invasion of Ukraine and the relentlessness of global warming hardly exposes a flaw in their thinking. To the contrary, the war highlights another reason to shift to renewables in addition to climate change: to end energy dependence on authoritarian petrostates like Russia.

In practice, though, not all sustainable funds are fossil-fuel-free. Not even close. Nearly 80% of sustainable funds globally have some exposure to the fossil fuel industry. For many, their exposure is relatively low and excludes oil majors or coal and more-controversial activities like Arctic exploration and oil sands extraction. Ironically, renewable energy funds tend to have higher levels of fossil fuel exposure than broadly diversified ESG funds. That's because many companies with significant renewable energy activities are energy and utilities companies that remain involved in fossil fuels.

Investors who want fossil-fuel-free portfolios can find them among sustainable funds. But those who want to invest in renewable energy may find it difficult to avoid some fossil fuel exposure. The larger point here is that sustainable investing, writ large, reflects the much more complex issue of the energy transition, and which companies specifically are funding it.

A Big Tent

It doesn't make for as good of a story to claim the war reveals flaws in the thinking of the 23% of sustainable funds that exclude military contractors or the 20% that avoid fossil fuels – but that would be a more accurate story.

There are all kinds of routes an investment can take to fulfill its goal of providing competitive investment results along with positive ESG outcomes. I wouldn't want a "high council on sustainability" or government regulators to define what sustainable investing means. There is no single path to sustainability or competitive investment results.

Sustainable funds could head off some of these broad-brush critiques, however, by being more transparent about their philosophies and the approaches they are using to achieve it. End investors can then make better-informed decisions as they match their investments with their sustainability preferences.

Jon Hale, PhD, CFA, is director of sustainability research for the Americas at Sustainalytics, a Morningstar company. Follow Jon on Twitter: @Jon_F_Hale

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6BCTH5O2DVGYHBA4UDPCFNXA7M.png)