Risk management is a serious business for all companies in the financial world and fund houses are no exception. Asset managers’ finest minds and heaviest computing power are devoted to looking at events and scenarios from the point of view of likelihood and seriousness. Like everything in investing, there’s a quantitative and qualitative approach, matching up the art of prediction with the science of investing.

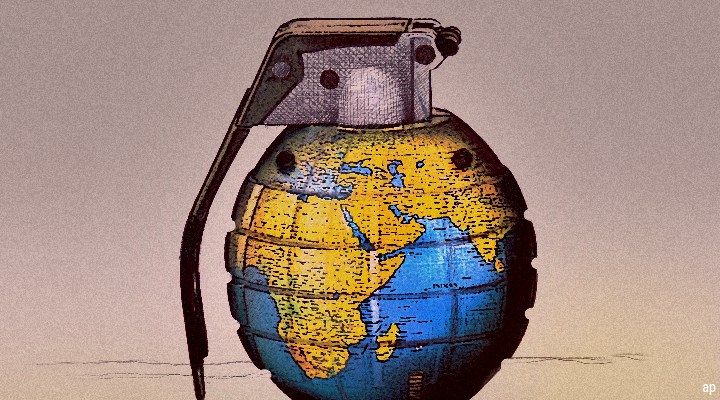

Arguably the two biggest global events in the last two years have been coronavirus and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The pandemic seemed more unexpected, but the risk of a global health scare has been discussed for decades, it's just that Western governments chose to downplay the warnings from scientists. Likewise, Putin’s move was unexpected but not beyond the realms of comprehension for military strategists. Hindsight is a wonderful thing.

Both events will affect ordinary people for years, and feel like “fork in the road” moments. But they also matter for investors. Both triggered a sell-off in “risk” assets (of which more later), one of which was severe, the other less dramatic. Risk assets are generally meant to encompass those that are volatile, rely on positive news about the world and the economy, but can make your money disappear when things go badly.

What is risk? It's the likelihood that somesthing goes wrong. When you drive a car you risk injury or death. Modern technology has reduced that risk, but it's a risk nonetheless. Ukrainians (and Russian soldiers) are facing the risk of loss of life on a daily basis.

From an investment point of view, risk may seem a trivial concept by comparison, but as investors we face painful risks all the time. There’s a spectrum here. At the most extreme, bad investments in companies that go bust, or scams, risk money disappearing. Think Germany's Wirecard or the old-fashioned boiler room scam.

Long-term risks, however, might be stocks or funds falling short of what you want or need, leading to a poor or unhappy retirement. But it cuts both ways. Advisers often note that pension savers take too little risk and regret it when it's too late to do anything about it. The results of not taking risk are also a risk.

10 Risks Russia Exposed

The science of risk and how asset managers control it is one for another article. But it’s worth taking a look at the Russian invasion from a “risk checklist” point of view.

1) Single country fund risk: whether it’s a Russia ETF, investment trust, or fund, investors in these products are nursing heavy losses and facing the extreme uncertainty of seeing their investments recover to pre-invasion levels. Who, apart from the incredibly optimistic, would buy a Russia ETF now?

2) Single stock risk: as our sanctions article shows, some individual shares are down significantly since the start of the year. These aren’t AIM punts either. Evraz and Polymetal are former members of the UK’s elite FTSE 100. A lot can change in just a few months.

3) Emerging market risk: some investors like to believe EM countries are “just like us” at an earlier stage but stocks are cheaper and GDP per head is lower. Prior to the invasion, Russia was part of the G20, had one of the most respected central banks in the world, and its companies were well capitalised and decent dividend payers. Not so much now.

4) Geopolitical risk: this is connected to emerging market risk. Regimes can go rogue overnight, but others were rogue all along and no one noticed or chose not to notice (see below). My colleague Tom Lauricella has opined on this.

5) ESG Risk: Investors may be happy to invest in undemocratic countries like China and Russia if returns are good enough. People invest in tobacco and arms companies. This selective amnesia over politically unpalatable countries has been severely tested since February 24. "China has been this incredibly lucrative emerging market to invest in, but there's been so little discussion of the regime," says Jon Hale, director of sustainability research for the Americas at Morningstar.

6) Currency: first the Turkish lira, now the Russian rouble. EM currencies can really tank, and fast. That can crush equity and debt investors' returns if things go south, and assets are denominated in local currencies.

7) Liquidity risk: Russia’s financial system has been placed into a deep freeze, making trading impossible. When it announced that some London-listed stocks would be removed from their indices, FTSE Russell explained: “the ability to buy or sell shares of the index constituents…is severely restricted due to major international brokerage firms no longer supporting trading of these securities and therefore there is insufficient institutional liquidity and market depth".

Premier Miton’s multi-asset manager Anthony Rayner says liquidity risk is often underappreciated until it’s too late: “An illiquid asset can appear to have a low volatility just because it doesn’t trade, though it often shows its true colours during a risk episode.”

8) Reputational risk: The list of multinationals withdrawing from Russia is significantly longer than those who stayed. Investors with stakes in Burger King and Nestlé will be asking tough questions of these boards this year. These companies attract negative news coverage and look exposed from a PR perspective.

9) Credit risk: investors in funds also had exposure to Russian sovereign and corporate bonds and they too have suffered as markets seized up.

10) Inflation risk: the Ukraine war has inflamed the commodity complex, and led to searching questions about where Europe gets its energy and food from. In the short term, it's given a jolt to already high inflation, reducing Western living standards and creating problems for governments already flagging from spending so much on coronavirus recovery. In the UK, the government is raising taxes in April but also giving some of this back to lower earners in recognition of the cost of living squeeze (council tax rebates and energy "loans" have also been thrown into the mix). This may ultimately impact how much extra cash investors have to put into their ISAs, for instance.

What's Changed?

The list could easily continue. But there’s a contrarian argument here too. The world appears to have changed dramatically in a month, but equity markets are back to pre-invasion levels, suggesting a degree of nonchalance from professional investors. So, as in the March 2020 panic, there was also a risk that investors sold during the market panic. Unigestion senior portfolio manager Olivier Marciot says this is still a dangerous environment for equity investors, who may easily leap before they look.

“The recovery in risk assets observed over the last two weeks looks like a bear market rally to us. Most equity markets are now trading higher than their ‘pre-invasion’ levels, in spite of deteriorating macro conditions and heightened risks over the medium-term," he says.

While the S&P 500 and other indices may look unruffled, the war is far from over and negative newsflow – such as the deployment of nuclear weapons – is likely to force investors to revisit all these risks again. As Morningstar Investment Management’s Mike Coop explains, many investors try to buy insurance during a flood, and not before. Complacent investors can't say they weren't warned if markets sell off sharply again.

Index Tracking: For and Against

Where does this leave investors who are extremely worried about this year but want to stay invested? It’s clear certain stocks and sectors – nuclear energy, arms, oil, natural gas, to name a few – look more attractive than before the invasion.

Premier Miton’s Rayner says this is a normal part of the sorting effect of the market: “Risk is not a static concept and, just as safe havens change depending on the main source of risk, so-called defensive equity sectors might prove to have a higher risk relative to other equity sectors if the main source of risk challenges that sector most.”

On one level we could surmise volatile market conditions favour stock pickers, and perhaps ones who can weight their portfolios to “war stocks”. Or alternatively, perhaps the Russian invasion has shown that index investing works? Earlier this month MSCI announced Russia will no longer be classified as an emerging market, taking the “Russia risk” off the table for EM investors (there's indirect Russian risk in investing in frontier markets like Kazakhstan, of course).

Likewise, FTSE Russell has shuffled Russian stocks out of the FTSE 100, 250 and All-Share indices. Stocks for the new world order are likely to gain a bigger weighting in future and push out the problematic ones. That’s at least the theory, but this can’t contain the messiness, unpredictability and risk of the real world.

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/Q7DQFQYMEZD7HIR6KC5R42XEDI.png)