A version of this article previously appeared in the March 2022 issue of Morningstar ETFInvestor. Click here to download a complimentary copy

There’s a lot to like about dividends. Getting a regular cheque in the mail from the companies you own is a testament to their discipline, the health of their business, and their confidence in its future.

But the prices of firms with stable cash flows tend to be more sensitive to fluctuations in interest rates than those with more volatile cash flow streams. Here, I’ll examine this relationship to understand whether it’s something investors should sweat over.

Asset Prices and Interest Rates Down by the Schoolyard

Imagine interest rates and asset prices as playground pals mounted on either end of a seesaw in the schoolyard. As rates rise, asset prices tend to fall. When rates come down, asset prices get a lift. These ups and downs are most pronounced for long-lived assets that produce predictable cash flows, like long-duration bonds.

While their cash flows may not be as stable or reliable as bonds’, dividend-paying stocks tend to exhibit a similar relationship with interest rates. Historically, the highest-yielding stocks have underperformed those that either don’t pay dividends or have lower yields during periods of rising interest rates.

The inverse has been true when rates have fallen: High-yielding stocks have trounced their less-generous peers. Exhibit 1 illustrates this relationship. I looked at monthly changes in the 10-year Treasury yield dating back to May 1953. In defining interest-rate environments, I counted the 25% of greatest month-to-month percentage increases in 10-year yields as “up” periods, the middle 50% as “steady,” and the 25% greatest month-to-month declines as “down.” Using data from Kenneth French’s Data Library, I examined the performance of US stocks across each environment, breaking the universe into dividend-payers and non-dividend-payers and sorting based on dividend yield.

The performance differences among stocks in the highest- and lowest-yielding deciles are pronounced during periods when rates are rising or falling. However, those spreads narrow significantly when rates are steady. And over the full period, the performance differential between high- and low-yielding stocks narrows further still.

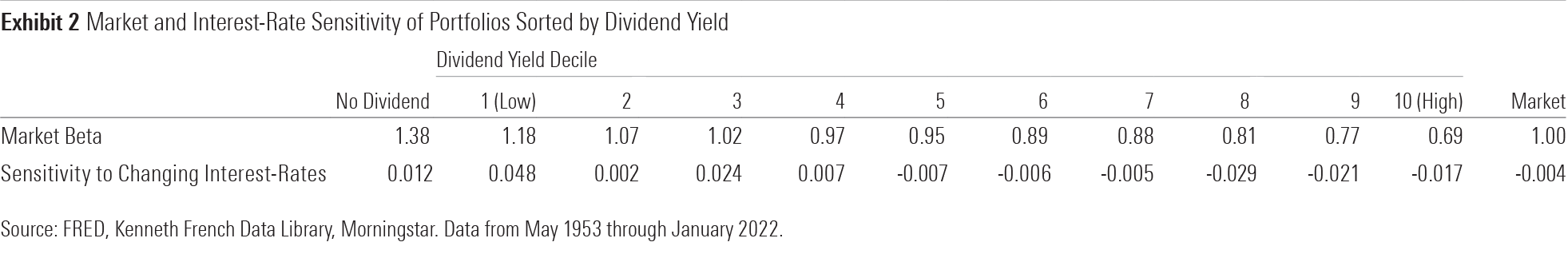

Exhibit 2 features the results of an analysis I ran on each stock portfolio’s returns. I measured each portfolio’s sensitivity to market and monthly percentage changes in 10-year Treasury yields. The values in the table indicate how sensitive each portfolio is to changes in the variable in question. A positive value indicates that the two tend to move in the same direction, while a negative value indicates an inverse relationship.

Equity risk was least pronounced among stocks that show more bond-like characteristics: the ones that throw off regular cash flows to their investors. These firms tend to be mature, and their businesses tend to be less cyclical than most. These factors allow them to commit to paying – and in some cases growing – their dividends over time. The market tends to punish firms that cut their dividends, so firms with more volatile cash flows will be more conservative with their dividend policies.

While higher-yielding stocks tend to have a low degree of sensitivity to market movements, they have a negative relationship with fluctuating interest rates. That’s no coincidence. Because they tend to have more-stable cash flows, higher-yielding stocks tend to have less growth when the economy is doing well to offset the negative impact of rising rates than lower-yielding stocks. Conversely, they get more of a lift when interest rates fall.

Sorting by Size

To better understand the relationship between dividend yields and interest-rate sensitivity, we need to connect the dots with companies’ fundamentals. Dividends are often a sign of maturity. As companies progress through their life cycles, their growth slows and reinvestment needs decline, allowing them to distribute more cash. Using market cap as a proxy for maturity, this evolution is evident.

Exhibit 3 shows the results of an analysis I ran on SPDR S&P 500 ETF Trust (SPY), SPDR S&P MidCap 400 ETF Trust (MDY), and SPDR S&P 600 Small Cap ETF (SLY). I used these funds as proxies for their respective strata of the market-cap ladder. As with the output featured in Exhibit 2, I measured their sensitivities to the market and monthly percentage changes in the 10-year Treasury yield.

The relationships here are clear. Large caps tend to be less sensitive to the market and changes in interest rates than their smaller-cap peers. This aligns well with the general characteristics of larger firms relative to their smaller counterparts. Specifically, they tend to be more mature and better capitalized and may have more-diverse revenue sources. These attributes lend themselves to lower market sensitivity.

Sorting by Industry

While looking at interest-rate sensitivity across market-cap strata helps ground this relationship in firms’ fundamentals, the picture is still far from complete. Examining how this relationship varies across industries paints a more vivid portrait. Exhibit 4 contains the results of a similar analysis I ran for 12 industry portfolios sourced from Kenneth French’s Data Library. Once again, I looked at each portfolios’ sensitivity to the market and monthly percentage changes in the 10-year Treasury yield.

Industries that are generally deemed defensive in nature – owing to inelastic demand for their offerings and ample pricing power – tend to be negatively affected by changes in interest rates.

These include utilities and consumer nondurable goods. Companies operating in these industries tend to produce steadier cash flows and thus tend to suffer as rates rise and get a boost when they fall. More-cyclical industries like energy and consumer durables exhibit the opposite relationship.

Demand for their output tends to ebb and flow with economic output, as do their cash flows. As such, they tend to get a tailwind from rising rates (which tend to be indicative of a growing economy, inflation, or both) and are hamstrung when they fall (often coincident with a softening economy).

Now I’ll drill down further, applying this same lens to a select universe of dividend-oriented exchange-traded funds that invest in US stocks that are also Morningstar Medalists with at least 10 years of performance history. I’ve run these seven funds through the same analysis outlined above. In Exhibit 5, they are ranked in descending order of their interest-rate sensitivity.

We see that Vanguard Dividend Appreciation ETF (VIG) has been the least sensitive to changes in interest rates and the most sensitive to movements in the broader market. The fund’s emphasis on dividend growth over dividend yield goes a long way toward explaining why it’s been less sensitive to fluctuations in interest rates than its peers.

At the bottom of the rankings, we find VIG’s yield-focused counterpart, Vanguard High Dividend Yield ETF (VYM). The fund tracks the FTSE High Dividend Yield Index, which captures the highest-yielding half of the universe of dividend-paying stocks in the large- to mid-cap US equity market. The index starts with the FTSE USA Index and ranks its constituents by their projected 12-month yield. It then adds stocks by descending rank until 50% market-cap coverage of the universe of dividend-payers is reached. This emphasis on dividend yield is the reason it is more sensitive to movements in interest rates than its counterparts.

Don’t Sweat Rising Rates

It can be helpful to understand how dividend-paying stocks and the funds that own them are affected by fluctuating rates. But it’s important not to conflate awareness and understanding with a call to action. Rates will rise and fall, and no one knows when or by how much. Owning quality companies that regularly return cash to shareholders is a solid strategy for all rate environments.

Disclosure: Morningstar, Inc. licenses indexes to financial institutions as the tracking indexes for investable products, such as exchange-traded funds, sponsored by the financial institution. The license fee for such use is paid by the sponsoring financial institution based mainly on the total assets of the investable product. Please click here for a list of investable products that track or have tracked a Morningstar index. Morningstar, Inc. does not market, sell, or make any representations regarding the advisability of investing in any investable product that tracks a Morningstar index

.jpg)