%20(1).jpg)

Investors in Russian stocks and bonds played with fire and have gotten burned.

In the wake of Russia's horrific invasion of Ukraine, stocks and bonds from Russia are being written off as essentially worthless, inflicting losses on investors.

But there is a broader lesson for investors to consider: when it comes to investing in autocratic countries such as Russia, the normal rules of picking stocks and bonds, such as valuations or the fundamental outlook of a company or country, can be rendered irrelevant overnight.

Sure, investors might make money for a while, but in the end, all that matters are the rules set by the person running the country. And often that means they are setting the rules to maintain power, enrich themselves and their cronies, or both.

It was one thing to miss the risks of investing in Russia. It's a country where most diversified investors have only a small percentage of their portfolio. It's a different story for a country like China. Many mutual funds and stocks have hefty direct or indirect exposure to the country, and observers who had warned about Russia are encouraging investors to ask similar questions about China.

"China has been this incredibly lucrative emerging market to invest in, but there's been so little discussion of the regime," says Jon Hale, director of sustainability research for the Americas at Morningstar.

The question directly confronting investors is whether "it is really sustainable long term to be investing in these kinds of countries," Hale says. It's "a systemic risk that we are all contributing to and that we should be paying more attention to."

And the reality has been that for more than the past decade, investors would have been better off keeping their money in the United States rather than sending it to Russia or China.

Two Risks

One way to look at these questions is to consider the two risks of investing in autocracies: geopolitical risks and rule of law.

Russia's attack on Ukraine is an extreme example of the geopolitical risks that come with investing in autocratic countries. The risk that investors are more likely to bump up against is rule of law.

Rule of law should be a primary consideration for investors, says Bill Browder, the famed hedge fund manager who made his fortune in Russia, only to be deported after run-ins with oligarchs and whose Russian lawyer was arrested in Moscow, mistreated by authorities, and died in a prison.

"You can do all the analysis you want on an industry, on the economics, on the management team, and then all of a sudden somebody comes along and rips you off, and you don't have any recourse in the courts, you don't have recourse in the media…and generally if they're not rule-of-law countries, you have no recourse with the regulators," he says.

"It's flying by the seat of your pants, hoping you're in the good graces of whoever is in charge."

Browder says he's heard various rationales and strategies for investing in countries like Russia. For example, investors should avoid strategic industries such as oil and gas that are likely to be closely aligned with the power structure and corrupt officials.

"Yes, you can invest in nonstrategic industries, but usually the only things aren't strategic are money-losing," he says.

Who's Lying?

There's also the lack of transparency in autocratic or authoritarian regimes.

Many mutual fund companies and professional investors like to talk about their "boots on the ground" research when it comes to stock or bond research. But consider the example of BlackRock's emerging-markets team.

As Morningstar analyst Samuel Lo noted: "The team running Silver-rated BlackRock Emerging Markets (MADCX) thought the odds of warfare were unlikely after some team members visited Russia in late January as the country mustered more than 150,000 troops on its neighbor's border. The fact that the population did not seem primed for a full-scale invasion and other factors, including cheap valuations, argued in favor of maintaining the strategy's long-term positions in Russia, the team said on February 16."

Of course, there were many observers who did not believe Russia would invade Ukraine. And it's not as if a mutual fund manager could ask someone in power if Russia was going to invade Ukraine and get an answer. But Browder says this reflects a broader point.

"In Russia and in places like Russia, [company managers and officials] lie and there is no shame in lying. They'll say: 'We have no intention of defaulting' and then default the next morning."

Tie it all together, Browder says, and investors wrongly think they can approach these markets the same way they do a market that operates on investor-friendly principles.

"You have somebody who says, 'OK, I've done my research, I've read Barron's and Gazprom is trading at 2 or 3 times earnings."

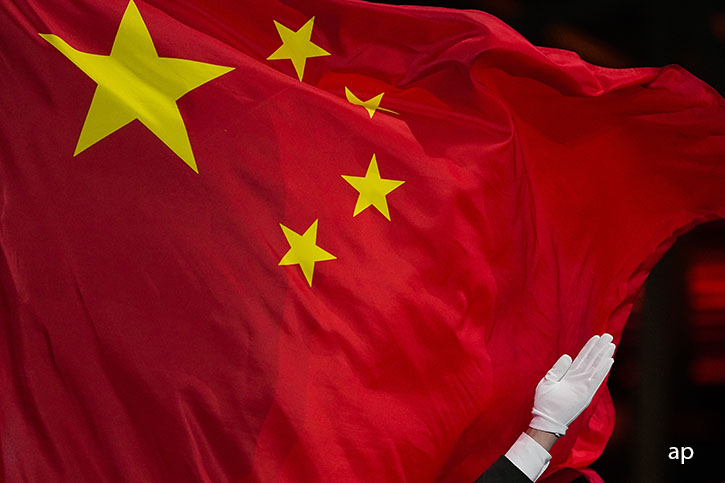

Parallels may be drawn between Vladimir Putin's designs on Ukraine and China's long-running claims on Taiwan. China has also been cracking down on freedoms in Hong Kong and has been persecuting its Uyghur population. But China doesn't have to go as far as invading Taiwan to show investors the risks that come with investing in the country.

Last summer the Chinese government imposed a regulatory crackdown on internet companies that included some of the biggest names in the market, ones owned by most emerging-markets and China stock funds, such as Alibaba (BABA) and Tencent (TCEHY).

Over the past year, Alibaba has lost nearly 60% of its value and Tencent more than 40%. Chinese regulators also took aim at private education companies. TAL Education (TAL) was one of the names in the crosshairs of the Chinese government, and its shares have lost roughly 97% of their value over the past year.

These moves, along with heightened tensions between the US and China over issues such as corporate disclosure policies for publicly traded stocks, hammered US investors in Chinese equities.

As Perth Tolle, manager of Freedom 100 Emerging Markets ETF (FRDM), recently said in an interview with Morningstar's Leslie Norton:

"From an investment standpoint, the biggest concern is not Russia, which is 3% of most benchmarks, but China, which is more than 30% of most emerging-markets indices. That's a huge concentration risk."

Says Browder: "Just because it's a big economy that's grown doesn't mean they're going to treat foreign investors fairly as they get more nationalistic."

Hidden Risks

Even if investors don't have direct exposure to autocratic countries, they may have hidden risks from companies based elsewhere in the world that do business in nations lacking in rule of law. A frequent example, says Shin Furuya, impact investment strategist at Domini Impact Investments, are energy and other natural-resources firms. "A European or Asian energy company might well be on the ground in Sudan, or the same thing with Myanmar," he says.

Energy and natural-resources companies often have to partner with state-owned enterprises, which makes it very difficult to disentangle from the risks posed by a government that might be involved in war, human rights abuses, or have a considerable degree of corruption.

Risk and Reward

For all these risks, there has not been much in the way of returns from Russia and China over the past decade. Prior to the closing of Russia's financial markets, the RTS Index had returned an average of 4.2% a year for the past 10 years, the S&P/BNY Mellon China Select Index 1.9% a year, and the Hang Seng Index negative 0.24% a year. Meanwhile, the Morningstar US Market Index averaged 14.9% returns for the past decade.

Browder notes that markets like China, while they have periods of outperformance, are afflicted by big drawdowns caused by political decisions . "If you're a trader, you can find moments when the markets are really bombed out, and then you trade out of it. But long term…there's just as much chance that you will lose money as make money."

Morningstar's Hale thinks that with investors being burned in Russia and China, perhaps awareness of regime risk will grow among investors. That could extend to countries such as Turkey and Hungary. "I think it will be considered more prominently than it has been in the past couple of decades," he says.

This article originally appeared on Morningstar.co.uk in March 2022, and is reproduced here as part of of Good Money Week