When fear of inflation creeps in, the big question is: is it transitory or permanent? For bondholders, it’s important to understand the implications of the answer.

If inflation is transitory, expectations of interest rate hikes weaken. If inflation is the beginning of a persistent or worsening situation, expectations of interest rate hikes will strengthen. That's because central banks have inflation targets - typically around 2% per year. And if the prices of goods and services increase too much, central banks can raise interest rates to curb the activities in their respective economies.

Increased inflation can hurt bondholders in two ways: 1) it erodes purchasing power if bondholders receive fixed payments while prices of goods and services spiral upward, and 2) it reduces bond values, conditioned that expected interest rate hikes are being priced in by the market. In this article, we will take a look at the latter effect – increased interest rates.

The Relationship Between Interest Rates and Bonds

The market interest rate is a key factor in determining the coupon rate (i.e., the periodic bond payments). That is why interest rate changes affect bond values. But remember that it is an inverse relationship - higher interest rates lead to lower bond values, everything else being equal. Similarly, reduced interest rates result in higher bond values, everything else being equal.

We will present two examples of this inverse relationship between higher interest rates and reduced bond value. Example 1): bond with short maturity, and example 2): bond with longer maturity.

Bond with Short Maturity

For the sake of simplicity, we use a zero-coupon bond with 1-year maturity (zero-coupon bonds do not distribute periodic coupon payments, rather they sell at a discount to the amount received at maturity).

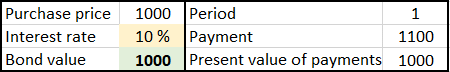

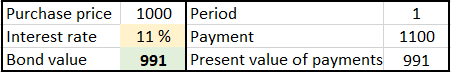

We purchase a zero-coupon bond for £1000. In one year, we will receive £1100, corresponding to an interest rate of 10%.

The day after our bond purchase, the central bank raises the interest rate to battle inflation. Interest rates have risen. Bad luck for us! We are seeing that similar bonds in the market now offer £1120 in one year, corresponding to 11% interest. We have an (unrealized) loss because no rational investor will pay the same amount (£1000) for our bond yielding 10% when they can buy a similar bond that yields 11%. But how much is our bond worth now that similar bonds are issued with 11% interest? The bond value must come down so that our bond also provides a return of 11%. This means that our bond is worth £991 (1100 / 1.11 = 991), a decrease in value of £9 or -0.9%.

Bond with Longer Maturity

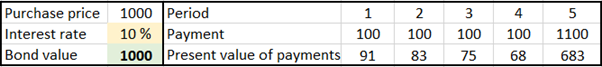

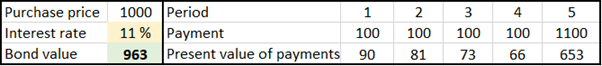

This time, we buy a bond with a 5-year maturity, coupon interest of 10%, and an annual coupon payment.

Yet again, luck is not on our side. The day after our bond purchase, the central bank increases the interest rate to dampen inflation. The interest rate hike means that similar bonds offer a coupon rate of 11%. How much is our bond worth now that similar 5-year bonds offer a coupon rate of 11%? The value goes down so that our bond also yields 11%. But in this case, we have to consider 5-years of payments. We expect a heavier loss for the 5-year bond than for the 1-year bond because of the time value of money. Our assumptions are correct as the bond value shrinks to £963 (the present value of 5 years of payments discounted at 11%), a reduction of £37 or -3.7%.

Conclusion:

The examples in this article provide information about bond values and their inverse relationship with interest rates:

1. The bond value decreases when the interest rate increases, everything else being equal.

2. Interest rate changes impact the value of bonds with longer maturities more than bonds with shorter maturities.

3. The value of a bond is the present value of all its future cash flows (basically the same principle as for the value of stocks).

One strategy to protect fixed-income portfolios against rising interest rates may be to reduce exposure to long-maturity bonds. We have seen that bonds with longer maturities are more negatively affected by increased interest rates than bonds with shorter maturities. Investors can also purchase floating-rate bonds or inflation-linked bonds to reduce the negative effects of inflation and interest rate hikes.

This article does not constitute financial advice. It is always recommended to speak with an advisor or financial professional before investing or making changes to your investment portfolio or strategy.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar's editorial policies.