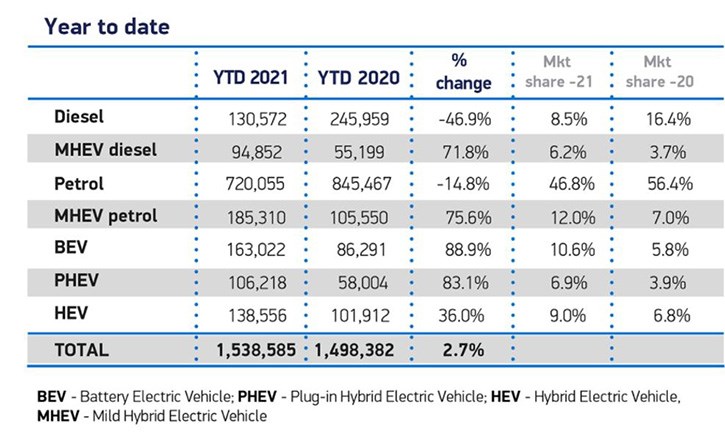

The latest UK sales data suggests that buyers of new cars are enthusiastically embracing the electric vehicle (EV) revolution. More than 160,000 battery electric vehicles (BEV) were registered to new owners in the year to the end of November, according to the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT), a near 90% increase on the same period last year (see table). Still, that’s about 10% of the overall total of new cars registered so far this year. As the EV industry expands, it seems to generate acronyms at a rapid rate – which means confusion for potential car buyers and for investors in the industry. Do you know your ICE from your FCV, for example, and could you tell the difference between an MHEV and a PHEV? Here we explain what some of the terms mean, and what Morningstar analysts think of the EV theme as an investment. We’ll look at the evolving battery technology space in a separate article.

When people think about electric vehicles as a replacement for the internal combustion engine (ICE), they usually have a BEV in mind. The battery electric vehicle (BEV) has no engine and produces zero emissions (assuming the electricity source to charge the battery) is from 100% renewable energy. Fuel cell vehicles (FCVs), which use hydrogen fuel, are an alternative to the BEV that are already on the market and also produce 0% emissions. FCVs can charge themselves on the go, unlike a BEV, and much more quickly than a battery powered car. Still, in the UK the range of models is more limited than the BEV, and there aren’t as many hydrogen filling stations as EV charging points.

Hybrids are a popular alternative as a half-way house, as they power vehicles via a combination of petrol/diesel egines and some form of electric power. These reduce conventional carbon emissions but are not emissions free. Hybrids have been on sale for a long time in the UK and US, and generally retail for less than the BEVs, which may account for their popularity (and ubiquity as taxis in cities). The SMMT data breaks down the different sales within the “hybrid” category into different varieties – and overall new cars with “hybrid” in the description make up 418,718, out of a total of 1.53 million.

Here we discover that the “mild” hybrid petrol car is the most popular sub-category, with 185,000 new registrations in the year to date, and the diesel version with 94,000. “Mild” may be something you associate with weather or illness, but a mild hybrid electric vehicle (MHEV) is a cheap and cheerful (and popular) way of reducing the CO2 emissions and fuel consumption of a traditional ICE. While the vehicle has a small lithium ion battery, it has an engine and you still put traditional fuel in the vehicle. They are less “green” than a plug-in hybrid vehicle and the UK tax treatment is less favourable. Plug-in hybrid vehicles (PHEV) saw a similar surge in sales to the BEV in the first 11 months of this year, rising 83% to just over 106,000 new vehicle registrations, even though they are more expensive than the MHEV. PHEV have an engine and a battery, and can reduce petrol/diesel usage by up to 60%, much more than an MHEV. And they have a longer range than than mild hybrid on electric power alone, but again not as much as the BEV. Costs generally increase the longer the range and the lesser dependence on petrol/diesel engines.

Power Up?

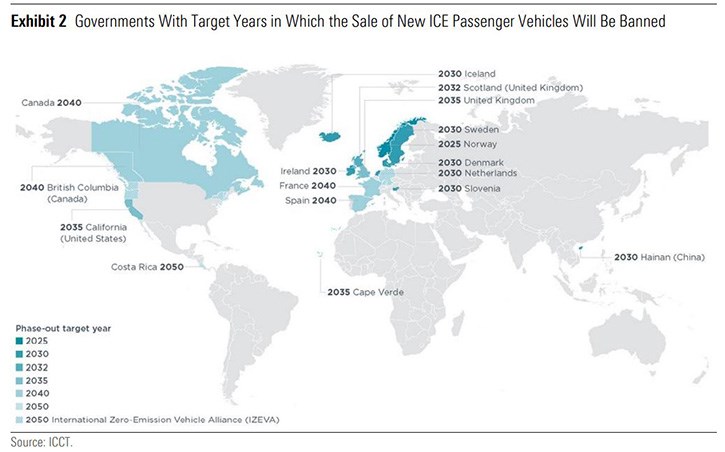

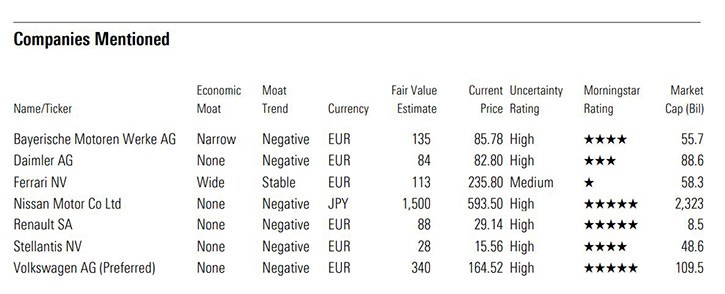

If EVs are soaring, and will make up around 30% of sales by 2030, surely this is an electric investment opportunity? Not necessarily, say Morningstar experts in their latest “Automotive Observer” which looks under the bonnet of the industry and how it is making the electric transition. While European automotive companies are selling many more electric vehicles every year, the theme itself is not an attractive investment opportunity, says Morningstar’s analyst Richard Hilgert. That seems like a paradox, but the shift to electric vehicles has been forced upon manufacturers by governments keen to meet net zero targets (see map).

That has meant rising costs for producers, and, as always, competition in the European industry is fierce. That’s great for consumers as there’s more choice, and prices are kept lower, but tougher on manufacturers which have to re-tool their whole production lines. Hilgert says that for most of this decade EV sales will match the decline in ICE sales, with the higher prices of vehicles sold balanced by higher costs. Petrol and diesel cars will no longer be sold in the UK from 2030 onwards, brought forward from 2035, but hybrids will continue to be sold until 2035.

While there are plenty of ETFs available to UK investors that specifically target the EV theme, Hilgert instead prefers to look at the car industry on a case by case basis, and at individual stocks. “We believe some automakers' valuations have been adversely affected by the upheaval the transition from internal combustion engines, or ICE, represents,” he says. Among the major European producers, Morningstar analysts prefer Germany’s BMW (BMW) because it is undervalued and has a narrow economic moat. (See table for the full list of stocks covered and their valuations).

Roadblocks

Sales of pure petrol and diesel vehicles combined in 2021 have fallen year on year to 850,627 out of a total of 1.54 million vehicles. While the trend is positive, there are some issues to address before we reach 2030. Supply chain problems have hit EVs particularly hard because of the shortage of semiconductors. A new wave of coronavirus infections in Europe, which has triggered more lockdowns in some countries, is likely to dampen demand for cars and travel in the short term.

Mike Hawes, SMMT chief executive , says that a lack of public charging pounts in the UK is a key problem. “The continued acceleration of electrified vehicle registrations is good for the industry, the consumer and the environment but, with the pace of public charging infrastructure struggling to keep up, we need swift action and binding public charger targets so that everyone can be part of the electric vehicle revolution, irrespective of where they live,” he says. The UK Government estimates that by 2030, the UK will need 400,000 charging points, but industry estimates are much higher. Website ZapMap calculates daily data and it says there are currently below 30,000 public points, but “slow” and “fast” charges outnumber “rapid” and “ultra-rapid” chargers.