The term “wide moat” is Warren Buffett-speak for competitive advantage. According to Buffett’s medieval metaphor, a wide moat is a company’s ability to withstand rivals—the same function a moat serves in protecting a castle.

“The key to investing,” Buffett wrote in a celebrated 1999 article in Fortune magazine, “is determining the competitive advantage of any given company, and, above all, the durability of that advantage. The products or services that have wide, sustainable moats around them are the ones that deliver rewards to investors.”

Morningstar has long used the moat concept as the foundational pillar of its stock analysis method. Analysts look for five characteristics when deciding whether to give a company a moat: intangible assets like brand or parents, cost advantage over rivals, switching costs to keep customers from changing providers, network effect and efficient scale.

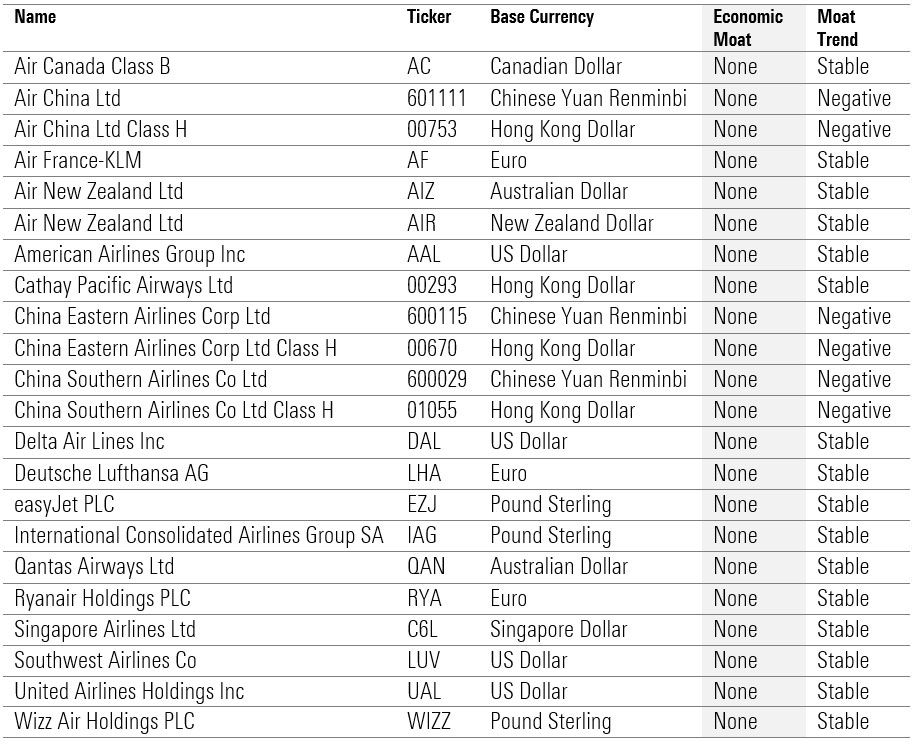

However, Morningstar equity analysts do not currently have any economic moats assigned to major global airlines. Analysts cite several structural factors including the fiercely competitive nature of the international travel industry, unpredictability of events that destroy investor capital and management's limited control over key external earnings drivers like fuel costs and exchange-rate movements.

"Airlines have traditionally been an industry where a no-moat rating is almost too generous, with an infamous history of value destruction as measured by subpar returns on capital," says equity analyst Burkett Huey. He says there are a number of factors that make it difficult for airlines to deliver decent returns: "A mostly undifferentiated product, a tendency for irrational competition, substantial operating leverage, and a tendency to employ financial leverage that exacerbates booms and busts."

And with 2020 a year to forget for most travel firms, it doesn't look like analysts' stance on the sector is about to change any time soon. Here are five reasons airlines don't have economic moats:

Morningstar Equity Global Airline Coverage

Source: Morningstar Direct

1. Commoditisation of Air Travel

You need to fly from Sydney to Melbourne. Both Qantas and Virgin offer a flight at the same time. Which one do you choose? The cheaper one, right? Hewitt says Qantas is selling a commodity good in a highly competitive market and cannot rely on cost advantage or switching costs to build a moat: "Air travel is perceived as a standardised product which, coupled with price transparency, leads to low switching costs."

While there is a perceived difference between budget carriers such as Ryanair and Easyjet, and more prestigious brands such as Virgin or British Airways, there is little else to separate airlines from each other, and that makes it difficult to generate brand loyalty. Travellers ultimately make their flight decisions based on cost and convenience.

2. Few Cost Advantages

A fiercely competitive industry creates downward pressure on flight ticket prices, says Hewett. He looks at Australia's Qantas as an example: "This elevated competition on international routes is reflected in the division's 15% EBITDA margin, which is lower than the 26% generated in the Qantas domestic division," he says.

Although movements in oil prices often lead to short-term swings in return on invested capital for airlines, their long-term profitability has little to do with fuel given that such costs affect all players almost equally. That means 2020's oil price crash was not the boon for the industry some might have assumed.

Hewett adds: "Reductions in fuel (or other input costs) are typically competed away, and savings are passed through to customers, reflecting the extremely high level of competition in the airline sector."

3. Lack of Loyalty

Several airlines, such as Qantas and BA, have attempted to garner customer loyalty with frequent-flyer programs, which aim to incentivise customers to fly with a particular airline.

"Consumers want to earn loyalty points when they fly, and status benefits are important for corporate passengers," Hewitt explains. "Qantas's program generates earnings from the sale of points to hundreds of partners, including banks, supermarkets, and department stores."

But while the capital-light Qantas Frequent Flyer business has somewhat cushioned Qantas's flying earnings volatility, Hewitt doesn't believe it creates a significant barrier to the competition.

"If you're part of a frequent-flyer program you'll probably be 'stickier' but there's a limit," says Hewitt. "How much extra are you going to pay to get those points? Maybe an extra $20, but $50 or $100? Probably not."

4. External Events

The global pandemic is fresh is everyone's minds, and we have seen in recent weeks UK citizen's banned from entering certain countries and a closure of the so-called travel corridors between the UK and various other nations. Such moves can destroy an airline's earnings overnight, and Hewitt says unpredictable events are part and parcel of the airlines business.

"A global pandemic isn't something we expect will be a regular occurrence, but demand disruptions are common within air travel," he says. "Terrorism, war, natural disasters, and epidemics are not that infrequent. Investors will remember the impact that events like SARS and 9/11 had on people's desire to hop on a plane. These events crunch travel demand almost instantly."

Hewitt says the highly capital-intensive and extremely cyclical nature of the business makes them prone to value destruction. "During the 10 years ended fiscal 2020, Qantas has incurred almost AUS$7 billion, cumulatively, in write-downs, impairments, and restructuring charges," he points out. "The most noteworthy was the almost AUS$3 billion fleet write-down in fiscal 2014, and more recently the AUS$1.4 billion impairment (mainly to the A380 fleet) in fiscal 2020."

5. No Barriers to Entry

Buy a plane and you're ready to go, right? Well, it's not that simple, but Hewitt notes that the barriers to entry for new airlines are low. Higher capital requirements are among the biggest sticking points, but airlines are able to lease their planes, which reduces the initial outlay.

While new airlines may need to build their brand and reputation, once they get off the ground they can take market share from existing players relatively easily if their price and proposition is right. Consider how swiftly Easyjet shook up the UK market, for example - the firm's fleet size grew by 62% between 2011 and 2019, and it transported more than 51 million passengers in 2019, compared to 44 million for British Airways.