One of the key features of bonds is capital preservation during a period of economic stress and stock market volatility. Bonds have again passed this test in a year of global pandemic and economic distress.

Investors have poured billions into the asset class as a result, pushing bond prices up to new highs. But one of the key features of bonds, the income element of fixed income, has gone missing in action this year. With more buyers ramping up bond prices, yields have gone in the opposite direction. Most UK Government debt has a negative yield, for example - unless you want to buy the 30-year gilt and wait until 2050 to get your money back.

While stock markets recovered sharply from the March carnage, fixed income has remained popular even with the paltry yields on offer. Our monthly survey of UK fund flows reveals that bond funds received £872 million of net new money in August alone.

The absence of yield has not put investors off, and part of the reason is the economic environment we live in – cash rates are negligible, dividends are being slashed or cancelled by the biggest companies, and inflation is on the back burner, particularly with many economies being put into hibernation this year. Interest rates are at record lows across the world and central banks look in no hurry to raise them – indeed, the Federal Reserve said that rates are likely to remain the same until 2023.

Why Panic and Bonds Mix

Why are bonds seen as a safe haven in economic turmoil? Governments, especially thoe with strong credit ratings in the developed world, are perceived to have very low default risk. (For more on this, check out our explainer on how bonds work here).

Morningstar Investment Management’s Mike Coop points says a key factor in the surge in bond prices this year is the intervention of central banks to buy bonds on an unprecedented scale.

“Why have bonds outperformed? In a word: pandemic! Central banks dropped rates to zero and starting buying bonds, inflation expectations fell and investors sought out safe haven assets as the pandemic caused a cataclysmic recession.”

Central banks have bought government and corporate bonds on an unprecedented scale to help stimulate the economy with cheap money and keep borrowing rates low. The Bank of England in April said it would double the amount of corporate debt it buys to £20 billion.

But Coop says the performance of fixed income has not been on a straight line this year, with the crisis of March and April the high point for bond returns: “It’s been like having three years in one: pre-pandemic (bonds underperfomed), pandemic crash (bonds outperformed hugely) and pandemic recovery (bonds underperformed).”

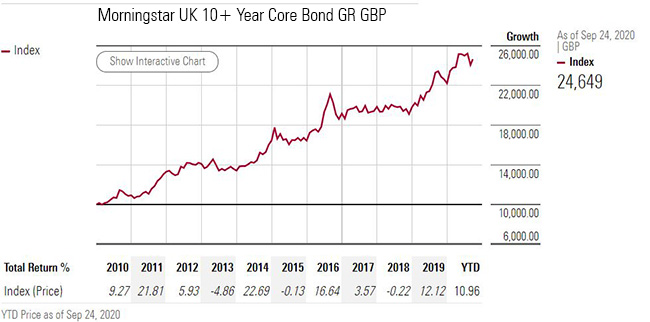

The most in-demand and therefore best-performing bonds this year have been longer-dated high quality debt. The Morningstar UK 10+ Yr Core Bond GR GBP index, for example, has returned more than 10% this year, while the FTSE 100 and FTSE AllShare are both down 23%. The last strong year for the index was in 2016, when the unexpected Brexit vote result rocked UK equity markets.

How have Morningstar’s top rated bond funds performed this year? There are three bond funds with a Morningstar Analyst Rating of Gold: Jupiter Strategic Bond (up 4% this year), Fidelity Moneybuilder Income (up 6%), and Invesco Corporate Bond Fund, (up 4.5%).

What Next for Bonds?

After a strong performance this year from both government and corporate debt, can investors expect the trend to continue? Jeff Keen, head of fixed income at Waverton Investment Management, says this year’s performance should be seen in the context of a 40-year bull market for bonds. For new investors in gilts, for example, there is little appeal right now, with high prices and low yields, he says.

Sonal Desai, chief investment officer at Franklin Templeton Fixed Income, thinks markets are pricing in low interest rates and low inflation – both great for bond prices – for a long time, but they may be wrong. Inflation, which is bad for bonds as it makes their yields less competitive, could make a comeback, she says, and the rise in company bankruptcies could make corporate bonds more risky than in previous years.