The UK equity income sector has been one of the worst performing this year as funds have been hit from all sides: Covid-19 has knocked a hole in income share prices, many blue-chip dividends have been scrapped and UK equities remain out of favour as Brexit negotiations drag on. The Woodford saga has also damaged sentiment towards equity income funds.

With these funds under pressure, how have yields changed in 2020 and over a longer time frame? As companies cut dividends, are these funds keeping up with the wider market?

In April, the Investment Association suspended the yield targets pegged to the FTSE All-Share, which affect the 87 funds in the UK equity income sector and the 57 funds in the global equity income sector.

Previously funds have had to deliver at least 90% of the yield of FTSE All-Share or face eviction from the sector, but the rules have been suspended until 2021. Without this move by the IA, the number of funds not making the grade would likely have resulted in a raft of ejections this year.

The IA said at the time that the new guidelines are designed to prevent any short-term disruption and allow savers to continue to easily identify and compare equity income funds. They are also designed to stop managers “yield chasing”, which would involve ditching the lower-paying but potentially more reliable stocks in favour of high-yielding, higher risk equities.

Yields Compared

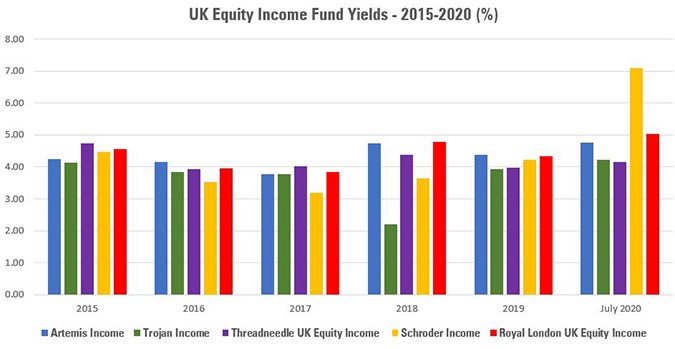

Using Morningstar Direct data, we’ve looked at the five biggest rated funds in the UK equity income sector by assets under management - Artemis Income, Trojan Income, Threadneedle UK Equity Income, Schroder Income and Royal London UK Equity Income – and compared yields across the last five years. Looking at the clean share classes for each fund, we’ve used the trailing yield at the end of the calendar year going back to 2015.

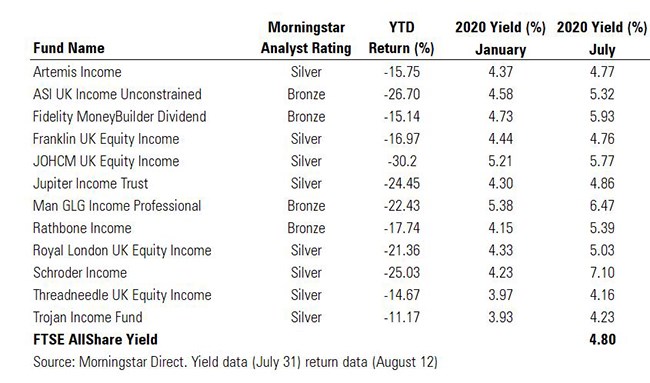

In all cases, the funds’ yields are higher than a year ago – as you would expect – and four-fifths of the funds’ yields are higher than they were at the end of 2015. But three of the five biggest funds are yielding less than the FTSE All-Share's current 4.8%.

One fund that stands out is Silver-rated Schroder Income, whose yield is up from 4.23% at the end of 2019 to a chunky 7.1% at the end of July 2020. This is 2 percentage points above the next highest yielder, Royal London, which has a 5% yield. What explains this above-average yield?

Morningstar analyst Robert Starkey explains: “The managers are ideally looking for stocks with a high dividend yield and income growth. Unlike many peers, however, they are willing to invest in companies that have cut their dividend, if they believe it reflects an inflection point in the company's strategy and share price.”

These value stocks are likely to have higher yields because their share price will have fallen harder this year than other names that haven’t cut their dividends – one of the fund’s biggest holdings is Imperial Brands (IMB), which is currently yielding more than 15%.

Looking at the wider list, four of the 13 funds that are rated by Morningstar have a yield below the FTSE All-Share, which suggests that were the IA’s rules still in place many would have been ejected from the sector.

Bigger the Better?

Investors may assume that bigger yields are a good thing, particularly if the overall goal is achieving an income. But this is not necessarily the case.

Companies’ yields move in the opposite direction to share price – so if a company’s payout remains the same and the share price dives, the yield will move higher. Funds operate in a similar way: a fall in the unit price of the fund will push up the yield if the payout in pence remains stable. Some of the funds that are rated by Morningstar are nursing losses of 20-30% this year.

Morningstar analyst Rajesh Yadav explains that a higher yield is not a good thing if the value of your capital has fallen. For example a £1,000 investment with a 5% yield means an income of £50. If the value of the investment falls to £800 then even if the yield climbs to 6% you are now only receiving an income of £48 - and the value of your capital has fallen.

Higher yields are an early warning sign of unsustainable dividends, too – Shell and BP were both yielding more than 10% before they announced they were cutting their payouts. Investors chasing the highest yields have to accept their taking a much higher risk. Income managers, from open-ended managers to those running investment trusts, have stressed the need for realism about yield among income investors this year.

When Will Dividends Recover?

Adrian Frost, manager of Artemis Income, says that dividends have historically been an important part of the total return enjoyed by UK shareholders. He adds: “But as this year has shown, these payments are not guaranteed and can evaporate during times of economic shock.”

Link, in its quarterly dividend report, says average yields on UK equities should pick up next year to between 3.6% and 4.1%, which is below the long-term average but roughly in line with the last few years – suggesting the coronavirus disruption may be temporary, at least in yield terms if not the overall cash value of the payouts, which may take years to recover.

Regardless of whether UK equity income funds are lagging behind the FTSE All-Share, a yield above 4% is still decent at a time when rates on cash accounts are negligible and Government bond yields are negative. And given the dire outlook this year, any change in sentiment, whether a resumption of bank dividends or Brexit progress, could revive the fortunes of these funds. Yadav says that sometimes investors get too hung up on the absolute yield number rather than the stability of the payout.

"It's important for investors to just not solely focus on yield number but focus on actual amounts of pounds and pence they receive from their underlying holdings and how stable that has been over the period and what are the risks investment manager is taking to get that income," he says.

.jpg)