The circumstances of the current market crash might be unique to the coronavirus pandemic, but they lead investors to wonder: are such drops normal for equity markets, or is this really different?

During the global financial crisis of 2007-09, some observers described the events that unfolded as a “black swan", meaning a unique negative event that couldn’t be foreseen because nothing similar had happened before. But data from Ibbotson Associates, a firm that specialised in collecting historical market returns (and which Morningstar acquired in 2006 and merged into Morningstar Investment Management LLC in 2016), demonstrated a long history of market crashes. Some ended up being part of a larger financial crisis.

So, if these “black swan events” happen somewhat regularly—too frequently to render them true black swan events—then what are they? They’re more like “black turkeys,” according to Laurence B. Siegel, the first employee of Ibbotson Associates and now director of research for the CFA Institute Research Foundation. In a 2010 article for the Financial Analysts Journal, he described a black turkey as “an event that is everywhere in the data—it happens all the time—but to which one is willfully blind.”

Here, we take a look at past market declines to see how the current coronavirus crisis compares.

How Frequent are Market Crashes?

The overall number of market crashes depends on how far back we go in history and how we identify them.

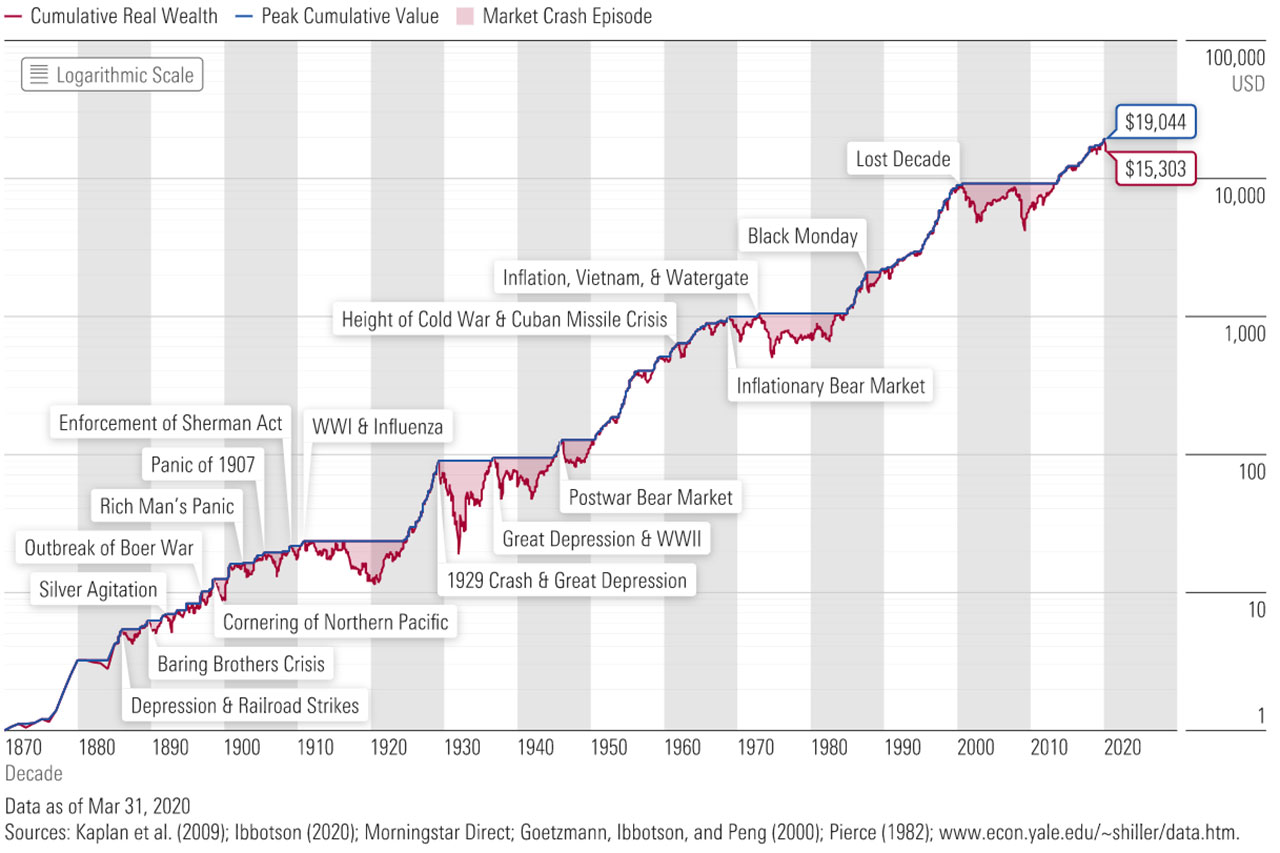

In this case, we consider market crashes over the past nearly 150 years. The chart below uses real monthly US stock market returns going back to January 1886 and annual returns over the period 1871–85, which were originally compiled for Siegel’s 2009 book, Insights Into the Global Financial Crisis. Here, I use the term “bear market” (generally defined as a decline of 20% or more) interchangeably with the term “market crash”.

Each bear-market episode is indicated with a horizontal line, which starts at the episode’s peak cumulative value and ends when the cumulative value recovers to the previous peak.

The chart shows that over this period of almost 150 years, $1 (in 1870 US dollars) invested in a hypothetical US stock market index in 1871 would have grown to $15,303 by the end of March 2020.

But it wasn’t a smooth ride to get there. There were many drops along the way, some of which were severe.

Market crash timeline: the growth of $1 and the US stock market’s real peak values

The market always eventually rebounded and went on to new highs, but it may have been hard to believe this during some of the long-term bear markets, including:

- The 79% loss due to the crash of 1929, which led to the Great Depression, the worst drop on the chart.

- The 54% drop from August 2000 to February 2009, also known as the Lost Decade. The second-worst drop on the chart, this period started when the dot-com bubble burst. The market began recovering but not enough to get the cumulative value back to its August 2000 level before the crash of 2007-09. It didn’t reach that level until May 2013—almost 12 and a half years after the initial crash.

- The 51% drop between June 1911 and December 1920. This market downturn, the fourth-worst on the chart, may be most relevant to today’s situation, since it included the influenza pandemic of 1918.

These examples show that market crashes have occurred numerous times throughout the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries (even before the coronavirus crash). Recognising their frequency can help provide a better sense of the risks of equity investing.

Measuring the Pain of Market Crashes

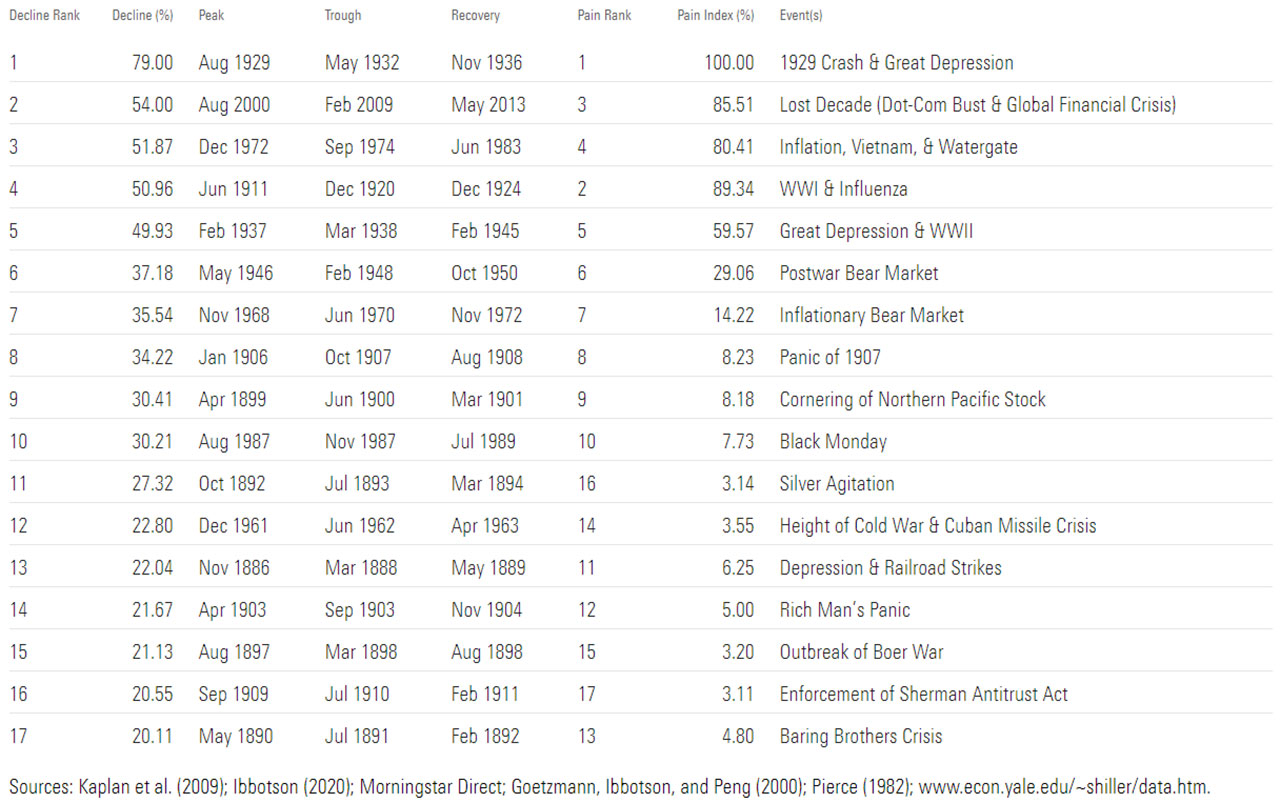

To measure the severity of each market crash in a way that takes into account both the degree of the decline and how long it took to get back to the prior level of cumulative value, we calculated a “pain index” for each one.

The pain index for a given episode is the ratio of the area between the cumulative value line and the peak-to-recovery line, compared with that area for the worst market decline of the past 150 years. So, the crash of 1929/first part of the Great Depression has a pain index of 100%, and the other market crashes’ percentages represent how closely they matched that level of severity.

For example, the market suffered a 22.8% drop during the Cuban Missile Crisis. The crash of 1929 led to a 79% drop, which is 3.5 times greater. That’s significant, but the market also took four and a half years to recover after that trough, while it took less than a year to recover after the trough of the Cuban Missile Crisis. So, the pain index, considering this time frame, shows that the first part of the Great Depression was actually 28.2 times worse than the Cuban Missile Crisis downturn.

The chart below lists the US bear markets for the past nearly 150 years, sorted by the severity of market decline. It also shows the pain index and pain index ranks.

Largest real declines in US stock market history

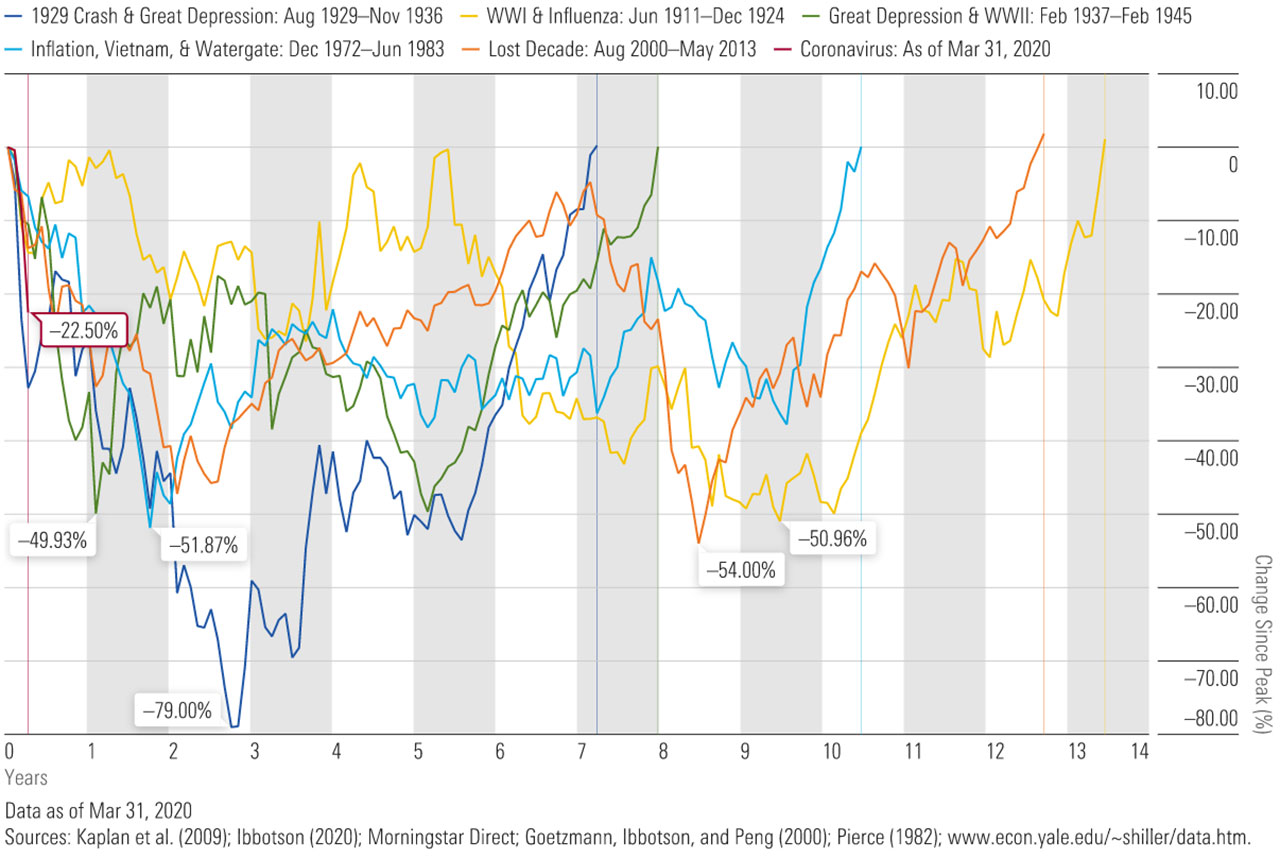

A direct comparison of the most severe market crashes

The chart below places the recent stock market sell-off into the context of the five other most severe market crashes to compare their time to recovery.

The 2020 coronavirus sell-off: how it compares to US stock market performance in the 5 most severe bear markets since 1871

In terms of steepness, the March decline was serious—it roughly matches the initial sell-off during the crash of 1929. The other most severe episodes include the inflationary bear market during Vietnam/Watergate, the second half of the Great Depression/World War II, the Lost Decade, and the World War I/influenza pandemic downturn previously mentioned.

Naturally, there’s a lot of variation in the length and severity of each episode. These five market crashes had an average of 57 months between when the decline began and when the market hit its trough; 125 months between when the decline began and when the market reached its previous peak; and a 57.15% decline.

In addition to these episodes, there were also 12 other bear markets over the 150-year period. Overall, bear markets have occurred roughly every nine years.

It’s impossible to know how long this particular decline will last and how long the recovery will take, but these averages make it easier to understand how many times the sky also seemed to be falling over the past nearly 150 years—frequently for longer periods of time—and that the market did always eventually recover its value, and then some.

This pattern is also present around the world. For instance, in Canada, there has been a market decline about once every seven years over the past 64 years. The nuances vary—Canada’s average time to recovery is about 34 months—but the overall trend of regular market crashes and subsequent recoveries is similar.

With Risks come Rewards

This historical stock market return data provides clear evidence that market crashes aren’t as unique as one might have thought. The term “black turkey” is more apt, since they appear every so often—and today’s coronavirus-caused crash is only the most recent example.

Given what this data shows about the regularity of market declines, it’s clear that market risk is about more than volatility. Market risk also includes the possibility of depressed markets and extreme events.

These events can be frightening in the short term, but this analysis shows that for investors who can stay in the market for the long run, equity markets still continue to provide rewards for taking these risks.

About the author: Paul D. Kaplan, Ph.D., CFA, is director of research with Morningstar Canada. He is a member of the editorial board of Morningstar magazine. Contributor: Nicolas Owens is editor in chief of Morningstar, Inc.

A version of this article appears in the second-quarter 2020 issue of Morningstar magazine.