The importance of diversification is one of the first lessons that any investor learns: spread your money across lots of different stocks, sectors and regions to reduce risk. But a number of fund managers fly in the face of that advice and are thriving as a result. Indeed, Warren Buffett once famously said “diversification is a protection against ignorance” and Morningstar Direct data shows that the most concentrated fund portfolios are often among the top performers of their group.

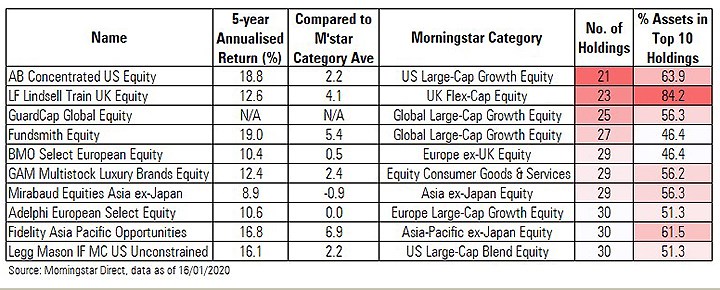

We have looked at funds with 30 or fewer holdings in their portfolio to determine how they have performed against their peers. There are 10 actively managed equity funds with 30 holdings or less, and seven of these have consistently beaten their Morningstar category (we do not have five year data for one of the 10).

The most concentrated open-ended equity fund is the Neutral-rated AB Concentrated US Equity Portfolio, with just 21 holdings in its portfolio. The fund has consistently outperformed its Morningstar category, US Large-Cap Growth, delivering annualised returns of 18.8% over five years, some 2.2 percentage points ahead of its category average.

A top performer in its category for 2019, it demonstrated how picking the right stocks can reap rewards. The main contributors to its stellar performance in the year were Microsoft and Mastercard, accounting for 9.7% and 9.5% of assets respectively.

Most Concentrated Open-Ended Funds

Of course, if a manager doesn’t make the right stock choices, making such large bets can severely hamper returns. Indeed, the main concern many investors have about concentrated funds is they can be riskier and more volatile than those which cast their net more widely.

Swetha Ramachandran, manager of the Neutral-rated GAM Multistock Luxury Brands Equity fund – which has 29 stocks in its portfolio – believes it’s just as risky to have a lots of different positions that don’t add any value. “Both approaches are risky, but we choose to invest with conviction with our research-led process, which should help mitigate the risk of single stock underperformance,” she says. The fund has delivered annualised returns of 12.4% over five years, some 2.4 percentage points ahead of its category average.

As the name suggests, the fund is focused on the luxury goods sector with top holdings including Ferrari and Kering. While the top 10 holdings account for some 56% of assets, Ramachandram says investments are only made after “intensive” due diligence. With Ferrari, for example, she spoke to competitors, customers and even former employees before deciding to invest.

She also points out that investing in a thematic fund such as this one helps to partially mitigate the risk of a single stock blow-up as there is a commonality of underlying drivers across all of the fund’s holdings – it does, of course, mean that they are all at risk if there is a sector blow-up though.

The Risks of Being Concentrated

One of the key risks of having so few holdings in a fund is it means that the performance of each stock has a significant effect on overall returns. When you own a basket of 100 different stocks and one goes belly up, the effect is fairly limited – but if a company collapses and it accounts for 10% of the portfolio, that could seriously hurt performance.

But Rob Morgan, investment analyst at Charles Stanley, says investors are paying active managers to make the right choices: “You pay active fees because you want them to run the fund actively, not just copy the index, and concentrated funds differ very much from their index.”

He adds: “Having a strong view and backing your own judgement by having a larger position could be a good thing. It’s the managers backing their own conviction.” In concentrated funds, managers focus only on their very best ideas and tend to hold on the stocks for long time.

“You don't buy things just because they're cheap, you buy because you want to own the business for at least 10 years or ideally forever,” says James Harries, manager of the five-star rated Trojan Global Income fund. His fund consists of 36 stocks, of which 30 of the holdings have been in portfolio since launch three years ago. Harries used to manage a 100-stock fund years ago and says it’s a very different way of running money: “We only sell when the valuation looks very full, when something fundamentally changes or when we have a better idea.”

High Concentration Means High Conviction

The Lindsell Train UK Equity fund is the second most concentrated fund in the group with 23 holdings – the top 10 account for a whopping 84% of assets. The fund is run by Nick Train, a manager notorious for his buy and hold approach to investing. But it was recently downgraded to Bronze from Gold by Morningstar analysts amid concerns about the fund’s growing size. With assets under management now at £9.5 billion, they believe this could restrict its investment universe and hamper future performance.

But the concentrated approach has certainly served the manager well thus far. It has delivered annualised returns of 15.3% over 10 years and was up 22.8% in 2019. The manager also runs an investment trust, which has even larger stakes in some of its holdings because it is not constrained by the same limits as open-ended funds, which are allowed a maximum of 10% of assets in any one holding.

Morningstar analysts don’t have a preference between concentrated or diversified funds defining themselves as agnostic when it comes to the number of holdings in a portfolio.

"What does matter is the manager's skills in picking securities," says Peter Brunt, associate director at Morningstar. He points out that different investment approaches are better suited to more or less diversification. Key variables could include the fund’s investment objective, the process, the restrictions on portfolio construction (such as regulations or simply prospectus limits) and the analytical resources available. "In light of these variables, we assess whether the concentration of the portfolio is appropriate," he says.

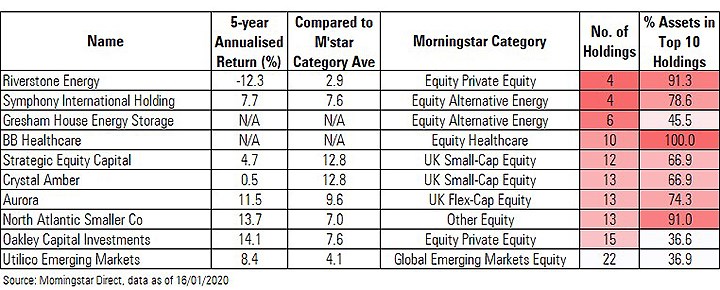

Investment Trusts Are Concentrated Too

Concentrated portfolios are just as common in the investment trust world, where at least 15 equity trusts have 30 holdings or fewer. This could be because the managers are able to take larger stakes in individual holdings or it could be that trusts can afford to take a longer-term view because they don’t have to deal with inflows and outflows. Brunt says: "Trusts don't have the same liquidity constraints, which means that managers don't have the same pressure about money being pooled in or out."

The specialist nature of some investment trusts means they have incredibly concentrated porfolios - indeed, three trusts in the list have just six holdings or fewer. Interestingly, of the investment trusts with a five-year performance record in this table, all have delivered greater five-year annualised than their category average. Even Riverstone Energy, which has lost money over that period is still done better than the average trust in its peer group, according to Morningstar data.

Most Concentrated Investment Trusts

Adam Khanbhai, co-manager of Strategic Equity Capital (SEC) thinks a portfolio of between 15 and 30 well-selected stocks can deliver the benefits of diversification without compromising returns. Currently there are 22 stocks in the portfolio, and the top 10 account for 67% of assets. He says having fewer stocks to monitor means he can research them more intensively and build a better relationship with the businesses he holds, which wouldn’t be possible in a 100-stock portfolio.