For investors, there are fewer more nerve-wracking moments than deciding how to invest a big cash windfall, the kind that might come from the sale of a business, an inheritance, or a hefty bonus.

The instinct among many individual investors is often to gravitate toward pound-cost averaging (PCA). This is the method of drip-feeding your money into the market, investing a little at a time and has become conventional wisdom.

It has been pounded into investors’ heads that it is folly to try to estimate the bottom or top of markets – so why make a big bet on the market by putting all that money into the market at once? Isn’t it smarter to invest it all gradually?

What investors don’t realise is that they are, in fact, making a market call by not making a lump sum investment. They’re betting that the stock market will go down for a while, and then come back up later. In the process, they’re adding more uncertainty to their portfolio planning.

In their paper, “Dollar-Cost Averaging: Truth and Fiction,” Morningstar’s Maciej Kowara and Paul Kaplan tackle the myths around lump sum investing (LSI) versus pound-cost averaging - or dollar-cost averaging (DCA), as it’s called in the US, and is referred to on the following charts.

They show that historically, PCA has produced lower long-term returns than LSI. At the same time, the returns from PCA are more uncertain than the results from LSI and when it comes to meeting an investment goal, this could mean greater risk. The full paper is available here.

Does Drip-Feeding Make You Richer?

Deciding to invest a lump sum into the markets is easily accompanied by a parallel fear: What if the market crashes tomorrow? Or next week? Or even next year?

The reality is that nobody knows what the market will do. The expectation that the market could crash next week is no more based on evidence than the idea that stocks could rally 10% next week.

What’s more important is to look at the math of pound-cost averaging versus lump-sum investing.

On average, PCA does not make you wealthier. When you expect the market to generate a positive return, delaying parts of your assets' entry into the market means giving up the gains that could have been gotten with the money that was sitting on the sidelines.

This point is illustrated by the record of the US large-cap market with data going back to 1926.

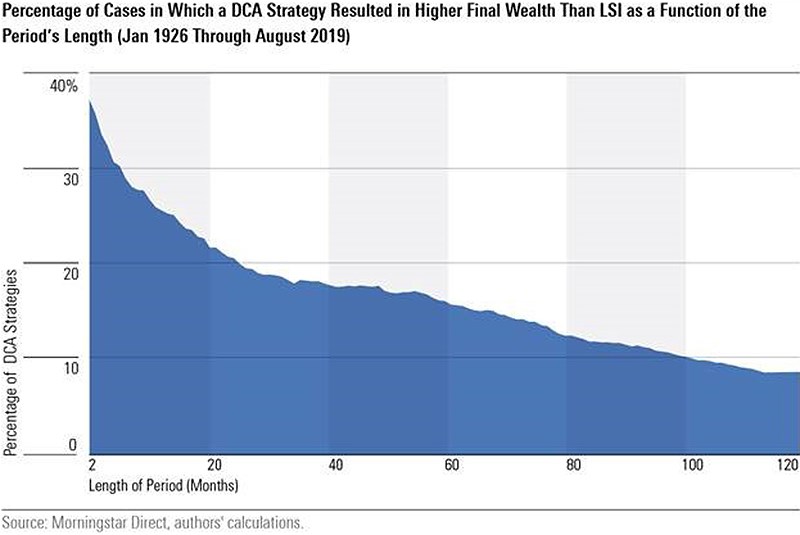

Kowara and Kaplan calculated the results of lump sum investing over all two-, three-, four-, up to 120-month periods and compared them against the final wealth achieved by spreading out the total investment into monthly segments over those same periods.

They then calculated the percentage of cases in which drip-feeding resulted in more wealth than lump sum investing for each time span.

The results: When you look over the average 10-year time frame, nine out of 10 times, an investor who dribbled money into the market would have ended up with less money than if they had simply put all their money into the markets at the beginning.

Although this may run counter to the conventional wisdom, the logic is easy to find: In a market that goes up, as US large-cap stocks have done over the past 100 or so years, the longer you delay your money’s entry into the market, the more likely you are to miss the gains that could have been gotten.

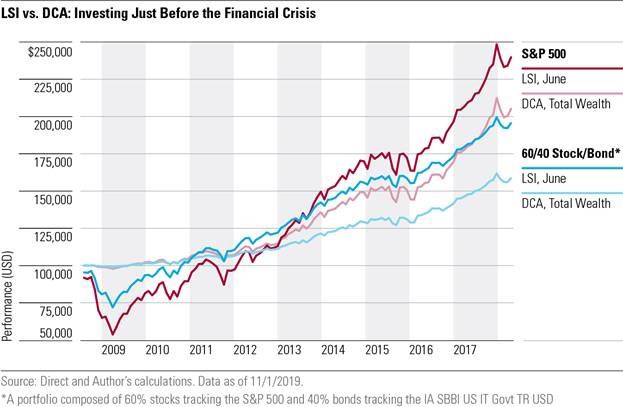

Of course, long-term averages hide the bumps. What if an investor were handed a £100,000 cheque in June 2008, just as the global financial crisis was about to break out? Wouldn’t it be better to have employed drip-feeding then, and captured the lower prices? No. Even in 2008, lump-sum investing would have been the better choice.

In the following illustrations, Kowara and Kaplan show both the results from a stocks-only portfolio and from a 60/40 balanced portfolio of the S&P 500 and bonds.

Despite the massive haircut taken to the investments in 2008, it isn’t hard to understand the reason for the outperformance of the lump-sum approach: since hitting bottom in early 2009, the US stock market has been in an uninterrupted bull market. And because the bear market happened early in the time frame, a lump-sum investor has had more time to recover and had more money in the market at the bottom than the investor who drip-fed their money in.

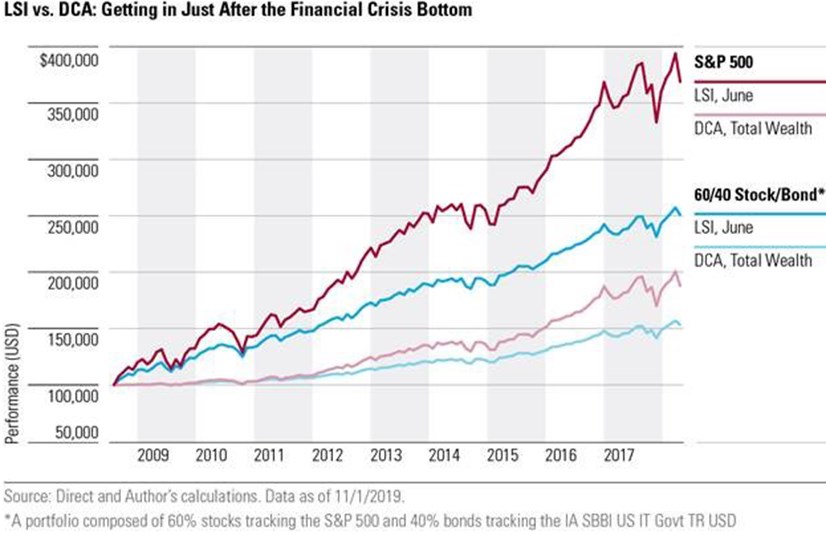

What about investors who got a windfall in June 2009, but - shell-shocked from the financial crisis meltdown - dribbled in their money instead of putting it to work all at once? They would have been left far behind by the bull market in stocks.

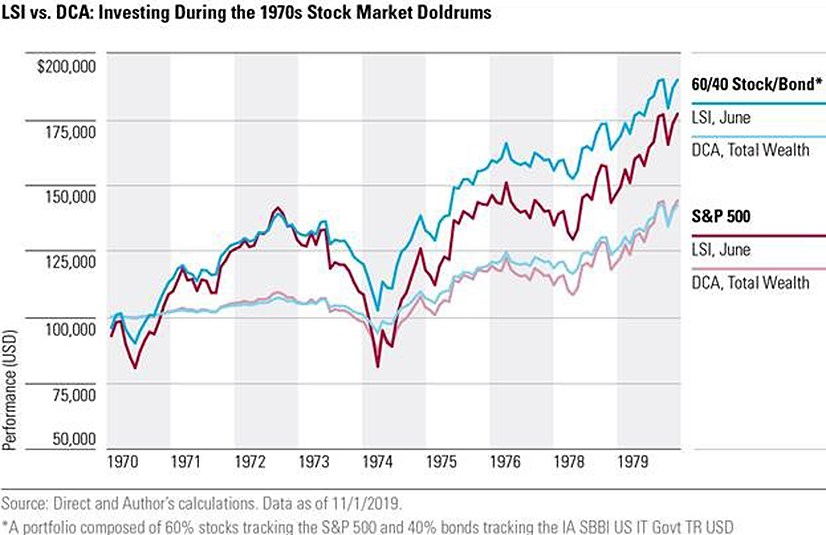

Of course, the stock market doesn’t always rebound strongly from a sell-off. What if stocks bounce back and forth over a long period of time, and essentially go nowhere? Here things get a little less clear-cut.

Perhaps the most famous example of a stock market going nowhere was the 1970s. In a US economy beset by “stagflation” and high interest rates, equities struggled throughout the decade. Still, in this case, there was enough upward movement that a fully invested portfolio, whether stock-only or 60/40, outperformed by 23% and 33% respectively.

However, it was a different story in the decade of the 2000s. With two bear markets in a 10-year stretch, the S&P 500 was down on an annual basis during this decade. In this environment, drip-feeding would have won out for the stocks-only portfolio, essentially because the stock market was down over that long-term time frame, an unusual occurrence. However, the 60/40 portfolio still benefited from the lump-sum investing strategy, outperforming the drip-feeding approach by 6%.

Does Drip-Feeding Reduce Risk?

This question of whether pound-cost averaging reduces risk is harder to answer.

That’s because returns from pound-cost averaging and lump-sum investing also vary depending on which method you use to analyse their performance. If you look at the “internal rate of return” (IRR) or “money-weighted return”, this takes into account flows in and out of a portfolio. However, if you use the “time-weighted return” (TWR) this strips out cash withdrawals and investments.

On average, the two methods produce similar results for pound-cost averaging or lump sum investments – but “internal rate of return” produces more volatile results than the other method. That means, using “time-weighted return” can give the impression that a drip-feeding strategy may be riskier than lump-sum investing.

To put it in plain English: With drip-feeding, it's more uncertain how good or bad an investment will turn out to be.

Is Drip-Feeding the Best Investment Strategy?

The fundamental problem with pound-cost averaging is that it’s a market-timing strategy. Holding money back and then investing it later only makes sense if you believe the prices of the assets you are planning to buy will fall for a while and then eventually rise. As it is unlikely that many investors are making such forecasts, then a drip-feeding strategy may not be the best choice.