Against the background of the UK pension freedom legislation, it is important that retirees have a reasonable expectation of the proportion of their assets they can withdraw each year to fund their cost of living, while ensuring sufficient capital remains to deliver a similar level of income into the future. This is commonly known as the ‘safe withdrawal rate’.

There is a growing body of literature on safe withdrawal rates for retirees, however most of this research is based on the historical returns of assets used by investors in the United States. Given the unique market environment for UK-based investors today, it makes more sense to base withdrawal rates off the expectations for UK-based investors than the history or projected returns for another country.

There are three primary findings from our research paper UK Safe Withdrawal Rates for Retirees. First, that while the historical performance of stock and bond markets in the UK has been relatively similar to the global average, future expected returns in the UK, especially in the near-term, are likely to be considerably lower.

Second, given these lower returns, safe withdrawal rates are relatively low, and may decrease further when incorporating future improvements in mortality – people keep living longer in retirement – and the impact of fees.

Finally, a balanced portfolio is likely the best allocation for UK retirees. Overall, while these findings are less optimistic than past research on the topic of safe withdrawal rates, they are nevertheless an important starting place for retirees and financial advisers today.

Initial Safe Withdrawal Rates

Research by Bengen in 1994, among others, suggests an initial safe withdrawal rate from a portfolio is 4% of the assets, where the initial withdrawal amount would subsequently be increased annually by inflation and assumed to last for 30 years, which is the expected duration of retirement. This finding led to the creation of the “4% Rule,” a concept that is often incorrectly applied: The “4%” value only applies to the first year of retirement, whereby subsequent withdrawals are assumed to be based on that original amount, increased by inflation.

Additionally, a retirement period of 30 years may be too short or too long based on the unique attributes of that retiree household. The analysis was based entirely on historical U.S. returns, which are not applicable for UK retirees today.

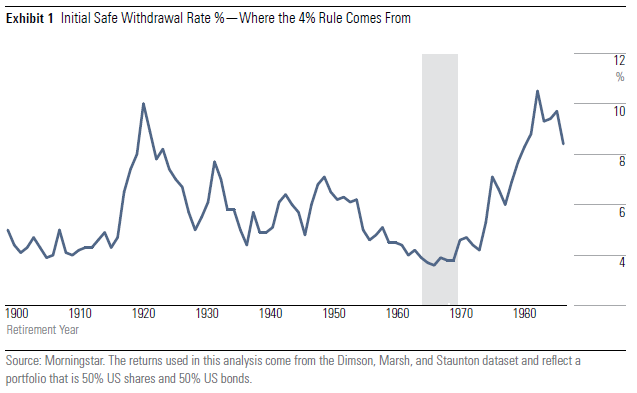

Exhibit 1 provides some insight as to how the “4% Rule” and other withdrawal rate heuristics have largely been determined. Exhibit 1 shows the highest initial rolling safe withdrawal rate for a U.S. retiree from 1900 to 1986, where retirement is assumed to last 30 years and the retirement income need is increased annually by inflation for the duration of retirement.

The shaded area shows the worst period for initial safe withdrawal rates over the historical test period and is effectively where the 4% rule originates as 4% represents the highest initial safe withdrawal rate for US retirees.

There are a number of problems extrapolating these results to UK retirees today. First, Bengen did not include fees in his original analysis. There is a definite cost to investing that needs to be considered when estimating withdrawal rates. Second, the analysis assumes retirement lasts 30 years, while in reality the expected duration of retirement, thus respective modelling period, should vary by retiree.

Third, this problem ignores the experience of retirees in other countries. Just because a 4% initial withdrawal has been safe in the US, does not mean it would have been safe in Italy, for example. Finally, it assumes that past returns are a reasonable basis for retirees today. While the past provides some window into the future, the markets today are in a different place than historical long-term averages, and this needs to be taken into account when advising a retiree on a safe initial withdrawal rate.

Historical Returns… An International Perspective

Return assumptions are a significant driver when estimating a safe initial withdrawal rate, likely second behind the length of retirement in overall relative importance. While historical US returns provide some context as to how safe a variety of withdrawal rates would have been for US-based investors, it does not create the appropriate historical context for investors in the UK.

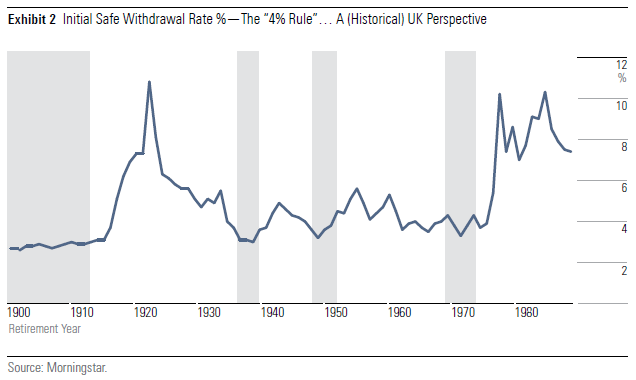

In Exhibit 2 we recreate the analysis in Exhibit 1, but instead of using historical US returns we use historical returns for a UK investor. We also include a portfolio fee of 1.00%.

Conclusions

Overall our findings suggest that financial advisers and retirees in the United Kingdom should use lower initial safe withdrawal rates than noted in prior research—the lower end of the range now starts towards 2.5% or 3% and not the previous 4%. The generous capital market returns of the prior century that bolstered a comfortable and long-lasting retirement portfolio may give 21st-century retirees a false sense of security.

Our paper also highlights the way probability of success can be used to understand potential outcomes. While expected returns are a mid-point operating at the 50% probability of success, our definition of “initial safe withdrawal” has been calculated in the range of 70% to 99% success.

Helping retirees understand the certainty of retirement incomes in this context is an important step to better meeting expectations. While this analysis provides a useful framework to consider the question of retirement spending, it also highlights the importance of understanding the specific needs and preferences of a retiree in framing investment objectives.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar's editorial policies.